December 15, 2016

Boston’s topography and its economically beneficial coastline leave the city exposed to severe flooding and extreme heat waves, the city warned last week with the release of its Climate Ready Boston report.

Based on current conditions, the authors wrote, if no environmental mitigation measures are taken between now and 2030, the city will face the threat of catastrophic damage to large swaths of the city from that time frame onward.

Conceding ongoing climate change, the report lays out several mitigation and preparedness strategies that would preserve existing resources and insure appropriate development going forward.

“Climate change is not a narrow issue, but one that affects the social and economic vitality of our city,” Mayor Martin Walsh wrote in introducing the report. “Climate action will not only keep us safer in the face of higher tides, more intense storms, and more extreme heat; it will also create jobs, improve public spaces and public health, and make our energy supply more efficient and resilient.”

The city’s waterways – three rivers flowing into a sheltered harbor – have been a boon for trade since Boston established itself in 1630. But today they are points of vulnerability with the prospect of sea levels in 2050 being 1.5 feet higher than the levels in 2000, the report notes, a uptick that could result in close to seven percent of the total land area of the city exposed to frequent stormwater flooding.

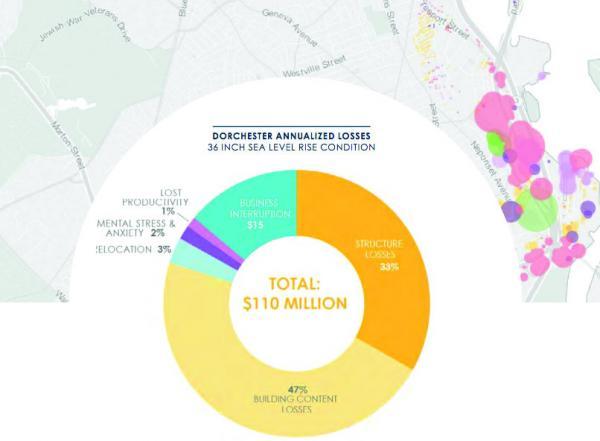

Dorchester’s sprawl along the coastline and the Neponset River leaves it vulnerable to “climate change impacts including heat, increased precipitation, stormwater flooding, sea level rise, and coastal and riverine flooding,” according to the report.

Areas along the Neponset could be inundated by an increase of up to 3 feet of sea level rise after 2070, the authors wrote. More immediately, they noted, Dorchester could become a conduit for flooding that reaches deeper into Boston, with extreme impacts within the neighborhood after 2050.

“As soon as the 2070s,” the report estimated,” close to 4,500 of Dorchester’s structures can expect some level of flooding from a low-probability event resulting in direct physical damage costs of $86 million.”

Flooding is already a common occurrence along the Dorchester coast. The heavily traveled Morrissey Boulevard is regularly closed or restricted to drivers by the overwash of high lunar tides or waves driven onto the roadway by the region’s stormy weather. An ongoing state Department of Conservation and Recreation redesign of the route could take almost a decade to complete if, as expected, the project takes place in stages and prioritizes the vulnerable middle section of road, officials told the Reporter last month.

“Frequent stormwater flooding is projected near major thoroughfares such as Columbus Avenue, Tremont Street, and Morrissey Boulevard, as well as Interstates 90 and 93 and along the MBTA Orange and Red Lines,” the report notes. “Additionally, many of these transportation routes are also designated evacuation routes, which may become increasingly more flood prone to coastal storms with heavy rainfall.”

One of the most immediately vulnerable areas in Dorchester is its northern coast, around Columbia Point. Projections for as early as the 2030s show a 1 percent annual chance of floodwaters leading to 9 inches of sea level rise at the end of Columbia Point below Joe Moakley Park in South Boston.

Although areas of Savin Hill are subject to more extreme and regular flooding during the same time period, other parts of Boston are more immediately at risk of flooding in the near term.

Aided by funding from the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management, the city will next focus on the East Boston Greenway and Charlestown’s Schrafft property site, two areas most likely to feel the impact of near-term flooding.

Downtown and South Boston will also be early focus areas, with those neighborhoods likely to take 70 percent of the economic losses in the case of a severe flood, seen as having a 1 percent annual chance of occurring between 2030 and 2050. The land around Joseph Moakley Park and I-93 is low lying, offering pathways for floodwaters that could reach South Boston, the South End, and even Roxbury.

Paul Nutting, an active member of the Savin Hill community who works for the state Office of Geographic Information, said the potential impacts extending beyond the immediate coasts are an unexpected hazard.“I think the most striking thing from the report is really the inland neighborhoods that could see flooding, because they don’t really think about it, because they aren’t near the ocean,” he said.

The area around JFK/UMass station, which, Nutting notes, were once ocean-side before the city filled them in, could quickly become an issue for those residents who assumed coastline flooding would, at most, disrupt their commutes.

“People who are in Andrew Square could be affected by what goes on at Carson Beach,” Nutting said. And for areas like the southern tip of Columbia Point, which could be cut off by flooding around the former Bayside Expo Center, Nutting said, “some neighborhoods are islands.”

An increasing frequency of heavy 24-hour rainfall events and spikes in heat waves will also impact large areas of inland Boston, the report said, disproportionately affecting populations of color and those with lower incomes or English proficiency.

As to solutions, the report has some proposals: By starting with consistently monitoring climate conditions, the city can then better attempt to educate and engage the communities depending of their specific levels of risk. Leveraging climate readiness can provide resiliency-based jobs and utilize underrepresented areas of Boston’s workforce.

Connecting direct stakeholders and establishing districts most in risk of flooding is just a first step in waterside protection, the authors wrote, particularly with the boom in coastal development. Engineering seaside structures to either stave off or weather the occasional severe flood would need to be implemented by flood district, depending on the areas at risk.

Climate Ready Boston is incorporated into the citywide planning initiative Imagine Boston 2030. Much of its resilience effort is funding dependent (The Barr Foundation, for example, has approved a $500,000 grant to support Boston’s climate preparedness initiatives).

In the event of an ambitious proposal like a harbor barrier, which would likely cost more than $10 billion, the report notes, Boston would be expected to coordinate with other cities, the state, and the federal government to address regional solutions.

Topics: