August 4, 2016

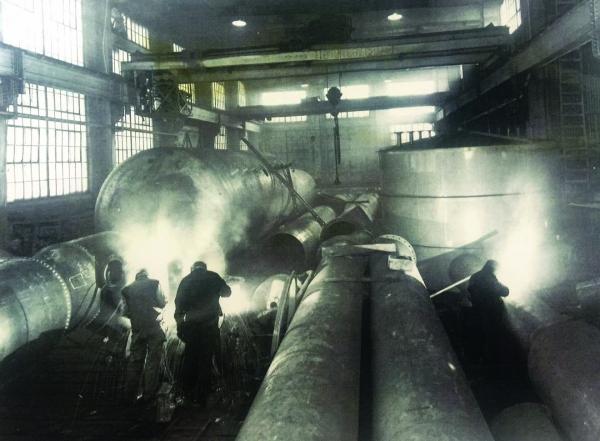

Workers are shown inside Russell Engineering Works in this undated photo from the mid-20th century. Photo courtesy Libby Russell

Over five generations, the Russell family built landing crafts to storm the beaches in World War II and hydrogen tanks for the space program. Richard Russell even engineered and supervised the construction of the foundation of one of Boston’s most iconic skyscrapers, the tower at Prudential Center.

They did it all from a sprawling complex of foundries and workshops tucked into a nondescript assortment of warehouses and sheds tucked along Dot Ave near Savin Hill.

Last week, after 142 years of Dorchester-based innovation and craftsmanship, the James Russell Engineering Works fired its furnaces for the last time. Richard Russell’s children, none of whom followed in their dad’s engineering footsteps, sold the firm to the Ohio-based conglomerate Worthington Industries in 2014, three years after their dad passed away at age 82. Last year, in a separate transaction, they sold the buildings and land for a reported $5.25 million to the Morningside Group, which is controlled by a China-based businessman named Gerald Chan.

Neither Chan nor his representatives have responded to the Reporter’s requests for comment about their plans for the property.

Managers for Worthington Industries had leased the space and continued to run the engineering works — which has been specializing in building vessels for cryogenic agents like hydrogen and liquefied natural gas — since the acquisition in 2014. The company’s lease ended on July 31, and operations were shut down two days before, according to Sonya L. Higginbotham, a spokesperson for Worthington Industries.

“The business was moved to our cryogenics facility in Theodore, Alabama, where they make a similar technology and have the space to accommodate the needs of the business with room to grow,” said Higginbotham. “When we purchased the business in 2014, we informed employees at that time that the business would be moved from its current location due to space limitations.”

Libby Russell, one of Richard Russell’s four children, has no direct say over what will be done with the property that Chan now controls. She says that the family had discussions with the developers of the massive DOT Block project that will create a new mixed-use community across the street.

“We weren’t able to come to terms,” said Russell, who added that she hopes Chan’s outfit will find a way to preserve some of the company’s footprint.

“I think it would be nice to see a mixed-use,” said Russell, who walked the perimeter of the two-acre site with the Reporter last week. The property is bordered by Dewar Street, which likely was named for her great-grandfather, Duncan Dewar Russell.

“I personally love the old, main building,” she said. “The windows are awesome; it’s a great space. It’s going to take some vision, but I’d love to see someone do something interesting with that.”

James Russell started his business in the 1860s as a blacksmith in the days when Dorchester was still an agrarian town, independent from the city on its northern border. In 1874, he launched a metal fabrication firm that focused on making large boilers. On the watch of Warren Russell, Libby’s grandfather, the company was enlisted to fuel the war effort in the 1940s, outfitting large barges and landing craft.

Her dad Richard, who attended Yale before serving in the war and then attending MIT like his father, was thrust into leadership earlier than expected due to his father’s untimely death. The post-World War II market was vastly different: the boilers that they company had mass-produced with such skill for decades were becoming obsolete.

“He inherited this company in a financial crisis,” said Libby Russell. “So he switched over to cryogenic applications. The company until very recently designed and manufactured vessels that that transport cryogenics— like LNG and hydrogen.”

It was not, of course, a one-man show. Up to 60 employees worked under Richard Russell as he re-tooled his family’s enterprise. A Yankee who was famously frugal, he was also deeply rooted in Dorchester and would make frequent visits to his grandparents home on Melville Avenue.

“My dad was known as an engineer’s engineer. He would hire people off the street who’d start at the bottom. One of them started as a broom pusher and is now one of the best aluminum molders in the world,” she said. “He didn’t believe in financing. They would run double shifts. But they were like a family. A lot of these guys were there for 30, 40 years.”

Russell Engineering Works building as seen from Dorchester Avenue in Aug. 2016. Bill Forry photoFor his part, Dick Russell and the family brand became known internationally for their high-quality, safe and durable cryogenic transports, supplying huge companies like Dow, DuPont, Monsanto and, as the space shuttle program ramped up in the 1970s, NASA.

Russell Engineering Works building as seen from Dorchester Avenue in Aug. 2016. Bill Forry photoFor his part, Dick Russell and the family brand became known internationally for their high-quality, safe and durable cryogenic transports, supplying huge companies like Dow, DuPont, Monsanto and, as the space shuttle program ramped up in the 1970s, NASA.

The company was seen as the “gold standard” outfitter for specialty, aluminum trailers that were custom made in Dorchester for long-haul use. “It is not uncommon for our own design/built products to be in use for 35-40 years,” David Hahn, Russell’s general manager, told the magazine CryoGas International in 2013.

Dick Russell was also proud to assist in the construction of the Prudential Center. He designed the innovative foundation of the 52-story tower – built in the early 1960s – using rolling cylinders to allow the building to better absorb wind pressures.

When her father passed away in 2011, Libby and her siblings attempted to take over, but soon realized that their skill sets were not suited for running an engineering firm. “We had a real crisis,” she said. “We had to sell the company to keep it going. [Worthington] was looking for a platform to get into the cryogenic transport business.

"Our people built the best trailers in the world. They would build the chassis here, and do repairs here too. We separated the land from the company because most buyers wanted to expand the business and you really can’t do it here,” she said.

Libby Russell says she is not sure what the new owner, Mr. Chan, who controls many holdings in Cambridge, will do with the Dorchester property, but she’s hoping that he will find a way to keep a connection to her family’s history.

“It was my understanding that he’s interested in preservation. I don’t know what he can and cannot preserve here. The blue building is not something you’d want to preserve. It’s just a big shed, so I don’t know.

“It could make for a very nice residential setting, she thinks. “It would be tricky, but I think it would also have water views when you get high enough.”

Villages:

Topics: