March 7, 2024

Community members signed on to the lawsuit were present in great numbers on Wednesday in the courtroom, with former School Committeewoman Jean McGuire (second from left) taking in the action. Pool photos by Jonathan Wiggs/Boston Globe

Judge’s ruling expected by end of March

Justice Sarah Ellis put a short hold on the White Stadium pro soccer and public school renovation plans on Wednesday during an preliminary hearing in the Civil Division of Suffolk Superior Court on Wednesday, pledging to decide whether the proposal can move forward by the end of the month.

The gravity of the matter was not lost on Judge Ellis, who noted the packed and emotionally-charged courtroom and promised to decide the case quickly – also getting assurances from the city that no demolition of the stadium inside Franklin Park would proceed until her decision is made.

“By March 13 let’s have a response filed by the plaintiffs, and by March 15 we’ll have a deadline for the defendant’s to file their response, upon which I will take the matter under advisement and endeavor a decision as soon as possible,” Ellis said, thanking the standing-room-only crowd of officials, litigants, and neighbors who had gathered to hear the controversial matter.

The judge had requested a longer time originally, taking the matter under advisement with a March 22 deadline, but city attorneys protested, saying they had already started a process to hire a contractor for partial demolition of the facility.

“The city does have a problem with that,” said Attorney Sammy Nabulsi, who noted the city wanted to continue the process of vetting construction managers and contractors and having public meetings but conceded “there’s not going to be any demolition in the month of March.”

Judge Ellis said the city could do whatever it wanted, but cautioned her decision could change everything.

“There is no injunction today that enjoins the city to stop its process, but any contract you enter into prior to my decision – you do so at your own peril,” she said.

The 90-minute hearing sought to flesh out the “true meaning” of a 75-year-old will, the necessity of the pro team to get cleats on the ground by 2026 or face financial ruin, and even an obscure legislative action in the 1950s that may or may not have declared White Stadium a “school building and schoolyard.” All matters of minutiae were laid out before the court.

The hearing was the result of a lawsuit filed last month by the Emerald Necklace Conservancy (ENC) and 20 residents against the City of Boston, the George Robert White Fund Trustees, and Boston Unity Soccer Partners – the lead group on a proposed public-private renovation of the dilapidated city-owned Stadium that would be shared by a women’s professional soccer team and Boston Public School (BPS) students.

Opposition to the matter has been strong from residents surrounding the park and community members afraid of being displaced by the pro team, but it has strong support from Mayor Michelle Wu – who has listed it as a top priority of her administration.

In court, both sides made powerful arguments.

“White Stadium is in need of repair — no doubt — and has been for decades,” said Attorney Ed Colbert, for the ENC and other plaintiffs. “It’s indisputable…But what’s the urgency today and why wasn’t there any urgency back then? The Stadium should have been repaired and it’s embarrassing it wasn’t, but there is no irreparable harm getting it right today.

“(Getting it right) can’t come later after the fact when demolition has already happened,” he continued. “It will be too late and there would be no remedy.”

Colbert and a panel of two other attorneys made the case that the current project would be illegal based on the last will and testament of George Robert White – whose money bequeathed to the city allowed it to purchase the land and build the stadium in the 1940s. Colbert said that transferring the property’s use – in this case through a lease and renovation agreement – would violate White’s intentions.

“If this project were to go forward…and the transfer of the site is made to a for-profit pro sports team as the plan leads us to believe, they will have violated the terms of the White Charitable Trust and it would no longer be for the exclusive use of Boston residents,” he contended.

The plaintiffs also cite their interpretation of the 1972 Public Lands Protection Act, or Article 97 in the Massachusetts Constitution – contending that the city and Boston Unity needs to go through that prescribed process, which would add a great deal of time that Boston Unity says is “onerous” and would result in “killing the project by delay.”

“It’s the law,” said Colbert. “There are lots of laws some people might find onerous or inconvenient, but it’s important not to lose any public lands or parks in our state.”

On the other side of the debate, Attorney Gary Ronan, of Goulston & Storrs, spent 45 minutes attempting to debunk those arguments and present the city’s evidence that neither the will, nor Article 97, applied.

“You heard from them this Stadium is going to be conveyed, or sold, or transferred to a for-profit entity,” he said. “That’s simply not happening…The question is whether the City of Boston can renovate its sports stadium that is in terrible shape…The City has a tremendous opportunity here to create a wonderful facility to be used by and benefit of the City of Boston students and used by the public…That is a public benefit.”

He also noted the property would remain under the ownership of Boston Public Schools, and under the auspices of the White Fund and that Boston Unity would only be leasing the property on very strict terms and would be contributing $30 million to the $80 million renovation project at their own risk.

“To talk about it as though they are taking away something from the public and student athletes is just inaccurate,” he said.

Ronan contends Article 97 does not apply because in the 1950s, the state legislature voted to grant a waiver to the 14 acres containing White Stadium, thus taking it out of Article 97 consideration and leaving the rest of Franklin Park under its protections.

“The state said the entire 14-acre site should be determined to be a school building and yard and shall be improved, altered, and expanded in the same manner as a school,” he said. “What is it not? It’s not an open park the residents of Boston have access to.”

Shortly after, he delivered a zinger to the court regarding the will, saying all kinds of organizations lease property from the White Fund, including plaintiffs ENC, who lease the Curley House in Jamaica Plain from the trustees.

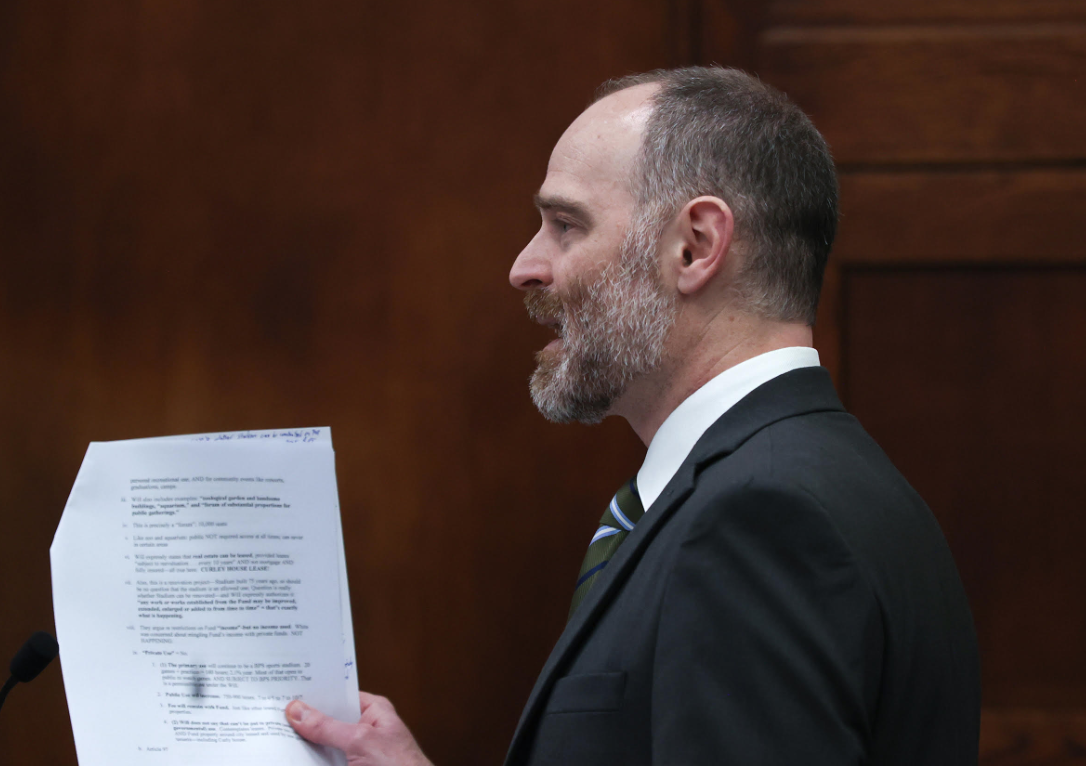

Above: Gary Ronan, of Goulston & Storrs, argued the counterpoint for the City of Boston in defending the lawsuit on Wednesday. Pool photos by Jonathan Wiggs/Boston Globe

“The ENC leases a building (the Curley House) from the George Robert White Fund,” he exclaimed.

“I suppose they would argue they are doing a service with their non-profit work,” said Judge Ellis.

“Oh, I’m sure they would,” smiled Ronan. “There is no difference in the will between for-profit or not-for-profit…as long as the property is being used for the use and enjoyment of the residents of Boston.”

Outside in the hallway afterwards, parties clashed on different viewpoints and public relations professionals from both sides rushed to get their points of view in front of members of the media.

At one point, BPS Cross Country Coach Hatim Jean-Louis teed off on those suing the city and Boston Unity.

“Not anyone here looks like any of the kids in the district,” he said, exasperated. “It’s one side. Who spoke with the kids and what they need?

Suing the city is hindering White Stadium and the future of Boston…The people making these decisions, do they look like BPS? I don’t see it.”

That comment drew the ire of Carla-Lisa Caliga and other community members attached to the lawsuit who were gathered in the hall, and a yelling match ensued.

“I’m a BPS parent with multiple kids and I’m going to tell you something, they have $50 million…,” said Caliga.

“I’m here to serve the kids,” said Jean-Louis.

“We’re trying to help the kids,” said another litigant.

“When?” exclaimed the coach.

“Now,” said Caliga.

“Where have you been the last 10 years?” asked Jean-Louis. “The city kids don’t know who you are.”

“I’m telling you, you are fighting the wrong people,” said Caliga.

The exchange was broken-up by a Court Officer who came out to disperse the loud crowd because it was disturbing other courtrooms.

Dorchester’s Louis Elisa, who is a member of the project’s Impact Advisory Group (IAG) and a plaintiff in the lawsuit, said he didn’t think the city and Boston Unity were being forthcoming.

“Now more than ever the request for an injunction is necessary because it seems the proponents are not being realistic when they give times about the improvements and things taking place there,” he said. “They’re not thinking through what is going to happen for real. They said the only time they will use it is for four hours with set-up and break-down and I say they’re not being genuine.”

On the other hand, Caroline Foscato, president of the Soccer Unity Project based in the South End, said, “I’m really excited about the opportunity to bring a professional women’s team back into the city to have our young women have representation and be able to have these role models right in their neighborhoods. It would really give BPS the state-of-the-art facility they’ve deserved for decades.”

Villages: