April 5, 2018

Residents of Dorchester and Mattapan are familiar with the paradox: Their neighborhoods, tethered to reputations as unsafe parts of Boston, are seeing encouraging declines in numbers of serious crimes while homicides remain disproportionately concentrated inside their boundaries. City and police officials are advocating for an intersectional approach to crime in the neighborhoods, highlighting increasing amenities and village strengths while working to reach individuals who may still view their zip codes as determinative of their futures.

“When I’m talking about incidences of violence, I don’t talk about Mattapan or Dorchester as violent neighborhoods,” City Council President Andrea Campbell said in a recent interview. “Instead, I pull it back and say, what causes incidences of violence in certain neighborhoods? Is it the quality of the neighborhood — concentrated in poverty, with low-performing schools, segregated, susceptible to redlining? Is this neighborhood receiving less resources for parks, open space?”

The rate of unemployment in Dorchester and Mattapan is consistently higher than the city average and household income levels are lower, according to the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey and projections based on the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“I’m pushing the city to direct resources to the very needs of the community so that the next time we don’t have an incident of violence,” said Campbell. “Instead, we have the young person graduating high school. It’s so easy to say, “we have a shooting and need to have a better response,” but it’s much more difficult and requires more work to do something about the poverty, schools, development, vacant lots, and properties.”

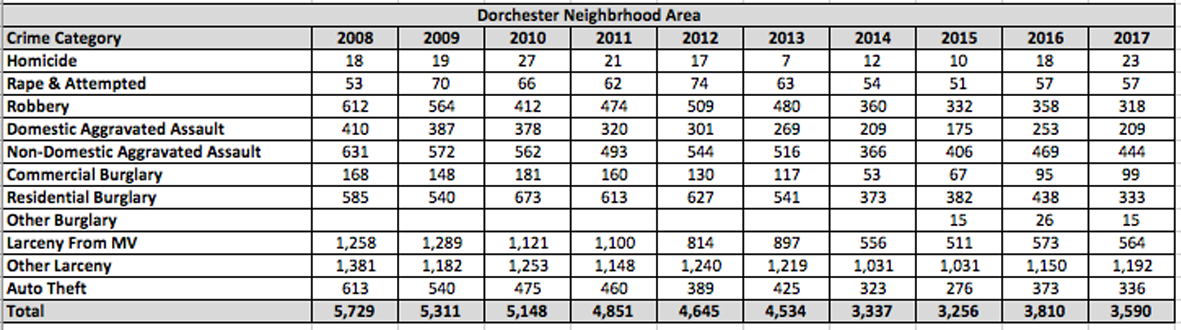

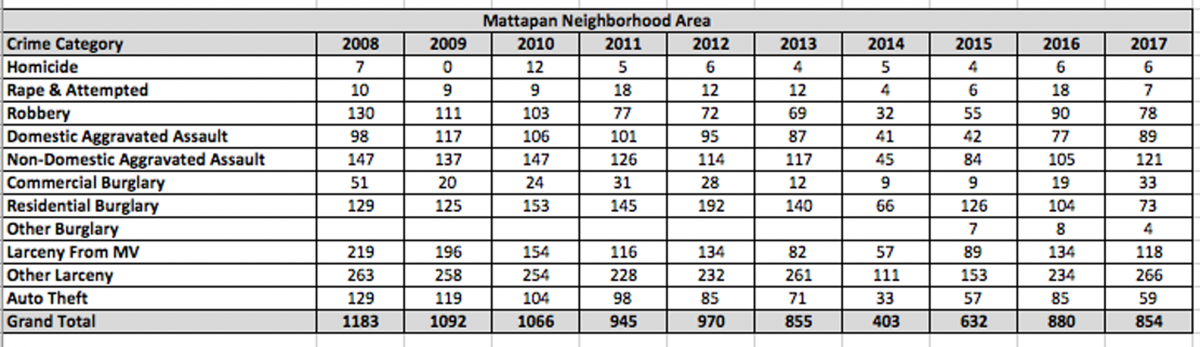

An end of year review of Boston Police data from 2008 to 2017 shows instances of homicides, rapes, robberies, aggravated assaults, burglaries, larcenies, and automobile thefts — which the department defines as part one crimes — are down by 27 percent in Mattapan and 37 percent in Dorchester with respect to neighborhood boundaries.

Despite a dip in Dorchester homicides from 2013 to 2015, murders in both neighborhoods have remained at about the same level, with a spike in Dorchester in 2017, even as their populations have grown at a slow but steady rate compared to the rest of the city.

In a Reporter mapping, Dorchester and Mattapan were the locations of at least 23 and 6 homicides, respectively in 2017. The proportion seems to be borne out in the number of murders this year as well. Of the 12 homicides so far in 2018, seven were in Dorchester.

Campbell, a Mattapan resident and councillor for the demographically diverse District 4, says there seems to be an evolution in attitudes about public safety moving south through the city.

“I think there has been some shift when talking about parts of Dorchester, I think a little bit less so with Mattapan,” she said. “In District 4, I not only highlight positive qualities of Dorchester and Mattapan. Residents who are actively engaged with their government, who are at the forefront of pushing for mixed-use development, such as [in] Mattapan Square, Codman Square with their farmers’ markets… These are the things I choose to highlight for both.”

In Mattapan, both Councillor Campbell and Boston Police Capt. Haseeb Hosein says an old, pejorative nickname for the neighborhood— “Murderpan”— grates on many longtime residents and on police, who have seen positive changes in recent years.

Hosein points out that the district he commands— Area B-3— has had a 10 percent drop in crime since 2016. Through last Sunday, April 1, compared to the same time last year, crime in B-3 was down 25 percent. It is the largest decline by district in the city, and level to last year, with a single homicide.

“How do we deal with the perception of it being ‘Murderpan?’ That’s hard,” Hosein said. One step is talking with more than 20 community groups monthly, “and every month when we go we stress that crime is down this much (22 percent) over three years.”

Of the city’s 57 homicides in 2017 – up 10 from the year before – areas B and C together – including Dorchester, South Boston, Roxbury, and Mattapan – accounted for 49.

Parsing the crime data by police district is useful in comparing geographic boundaries and change year-by-year, even if there is not a clear neighborhood profile or population estimate associated with it. C-11 falls entirely within Dorchester, though the neighborhood sprawls into significant portions of C-6, including most of South Boston, B-2, including much of Roxbury, and B-3, which is split between Dorchester and Mattapan.

The district boundaries “really are historical,” said police spokeswoman Rachel McGuire. “They have not changed in the recent past really at all… We’re not especially concerned so much with district lines, but more in terms of where is the crime occurring, how do we address hotspots, and where should we allocate resources.”

The reallocation of police resources occurs constantly, she said — daily, weekly, monthly — based in part on these hotspots.

It is up to district captains to guide the community policing within their districts. Capt. Tim Connolly, who just finished a two-year stretch as commander at C-11, said he often tried to contextualize the types of violence being perpetrated. “I explain that, hey, these aren’t random shootings, and 95 to 99 percent of them are targeted between different gangs and the violence that has been associated with that,” he said. “They’re hits. They’re assassinations.”

C-11 also saw a 10 percent drop in part one crime in 2017, and as of April 1 is looking at a 17 percent decline over last year, although up one homicide to three total.

Since some types of part one crime are much more common — larcenies account for about 58 percent of all part one crime and occur far more frequently in districts like the South End’s D-4 and Downtown’s A-1, each of which saw two homicides in 2017 — smaller proportionate downward swings in larcenies can completely overshadow increases in more serious crimes, like homicides, which account for 0.3 percent of overall part one crime in the city.

For Campbell, “there’s no separation in terms of categories. Violence is violence, so that’s how residents expect us to talk about it. Remember that even if incidences of violence are decreasing in communities, if there is one larceny, one homicide, that shakes the core of community, because they don’t care that violence numbers are going down, they care about that one incident.”

“We need to be mindful of what they are feeling,” she said. “A decline usually doesn’t bring them comfort.”

Connolly and Hosein both say that allaying community fears with overall drops in crime is still a regular part of the job. Each violent incident kicks up a new round of concern from Mattapan and Dorchester residents, Hosein said.

“Within the neighborhood, it’s the fear of crime, right? Every time there’s a shooting it gets glamorized, it gets TV coverage,” he said. Though the homicide and shooting count has been on a moderate downward trajectory, “it’s the number of shootings and the number of homicides that perpetuate the ‘Murderpan” story,” he said.

Warm weather is on its way, and with it the seasonal spikes in violence that accompany more time outdoors and school being dismissed for the year. Hosein noted that even as homicides remained level or increased slightly, incidents involving teenagers have doubled since last year.

Much of the police time and attention is therefore spent on education, coordinating programs like Chelsea-based Roca to talk with high-risk young men, to innovate ways to divert younger kids from going down a damaging path, he said.

“We still need to engage with the schools and the kids, we still need to get the message out any chance we can that crimes down,” he said. Again, just “working on the fear of crime, working on that large history of Murderpan and Mattapan.”

Some of it comes from within the neighborhood, he said, and there is an additional burden on young people to represent themselves well even if they do not have many models for how to do so.

“With the kids, it’s just working with them to deter them from becoming the statistic,” Hosein said, in a rueful tone of voice. “Stop playing into stereotypes because we’re a black and brown neighborhood. The crime has to stop.”

Most policing takes place quietly and strategically around removing guns from the street and watching hotspots, the captains say. Both districts are using Cam-Share pilots that allow police to monitor private cameras through a voluntary program.

But increasingly they have been building up connections between the districts and the community fabrics. Connolly said C-11 stays connected with local business districts like Bowdoin-Geneva through a shared messaging app, and Hosein highlights partnerships with the Department of Youth Services.

“Over the past 10 years, we are seeing a downward trend, and it’s pretty steady, and that has to do with the fact that we are out there and we’re always assessing where we need resources and what does the community need,” McGuire said. “We work with the community to get them what they need, whether it’s more of addressing quality of life issues or more officers addressing homicides.”

She pointed to restructuring around the homicides unit in 2012, where extra detectives were added to the unit amid expanded training. “The whole thing is, if the community asks for it, basically that’s what we’re going to give them,” she said.

The community can help to fine-tune her council priorities and requests for additional resources, Campbell said.

“My residents know how wonderful and diverse and vibrant those districts are. Those who choose to learn about the community from media spaces versus visiting, they’re the ones who I often have to push back on.”

Topics: