November 17, 2016

A graphic from the Boston Foundation report illustrates the high rate of incarceration in several sections of Dorchester.

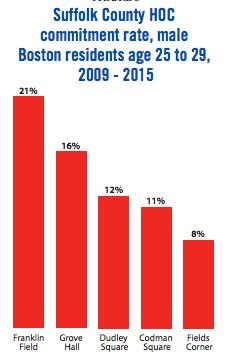

The imprisonment rate of residents of Boston’s communities of color – areas of Dorchester and Roxbury – are consistently double and triple the city average, according to a recently released Boston Foundation report titled “The Geography of Incarceration.”

City and state officials discussed the report at a panel discussion last Thursday where the following were among the findings:

• “In Franklin Field and Grove Hall, virtually every block was impacted by incarceration, and on many streets several residents were committed during the course of just one year.”

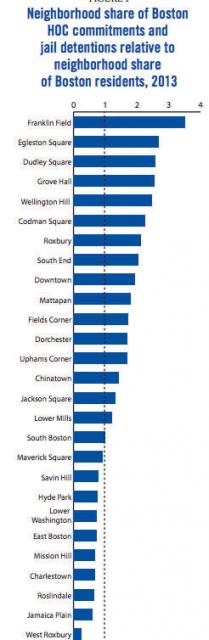

• Though only 1.4 percent of the city’s population resides in the Franklin Field section of Dorchester, that neighborhood accounts for 4.9 percent of the city’s commitments to the Suffolk County House of Corrections.

• More than one in five male residents age 25 to 29 in that area were imprisoned between 2009 and 2015, the highest rate in Boston.

The Boston Foundation collaborated on the report with MassINC and the Massachusetts Criminal Justice Reform Coalition. Last Thursday, Suffolk County Sheriff Steven W. Tompkins, state Rep. Evandro Carvalho, District 4 City Councillor Andrea Campbell, and John J. Larivee, president of the nonprofit Community Resources for Justice, talked about the impacts of such high rates of imprisonment on the communities that they serve and study.

After the discussion, Boston Foundation President Paul S. Grogan said that his organization is interested not only in the impact of widespread incarceration, but “also in human capital, in what kind of talent we’re going to have in this city that will continue to power the economy.” He added, “To have such a large number of particularly young African-American men incarcerated is really devastating.”

Imprisonment crosses generations, Tompkins said, recalling cases where grandfathers, fathers, and sons from the same household were incarcerated simultaneously at various stages in the prison system.

Boston Foundation Incarceration ReportThe disruption this causes in a community can be enduring, the report’s authors wrote, particularly when incarceration affects 50 percent of households in some areas of the city. The data “should serve as a wakeup call as leaders in Massachusetts consider how to reform a criminal justice system that has had disproportionate impact on urban communities like Boston, and especially destabilized high incarceration rate communities.”

Boston Foundation Incarceration ReportThe disruption this causes in a community can be enduring, the report’s authors wrote, particularly when incarceration affects 50 percent of households in some areas of the city. The data “should serve as a wakeup call as leaders in Massachusetts consider how to reform a criminal justice system that has had disproportionate impact on urban communities like Boston, and especially destabilized high incarceration rate communities.”

As rates spike, the neighborhoods consume correspondingly high amount of taxpayer resources. Dorchester comprised 18.6 percent of Boston’s population in 2013, but its 277 incarcerations were 33.7 percent of citywide commitments. Taxpayers were on the hook for $13,904,400 to house those prisoners.

Boston spent $66 million in 2013 in prison costs, a figure, the report notes, is twice the city’s combined $39 million budget for the Parks and Recreation and Youth and Families departments.

Given those kinds of numbers, Tompkins said, sheer economic pressure could be a driver for action. “Enough is enough,” he added, “We cannot any longer afford to incarcerate as many people as we do.”

To an extent, the report “doesn’t tell us anything we don’t already know,” said Rep. Carvalho. Some neighborhoods see prison as so normalized that it may lose its impact as a deterrent, he and other officials said.

“For me, it paints a picture of despair, but it also creates a sense of urgency,” Councillor Campbell said after the discussion. “So, when you look at districts where going to prison and spending time in prison is the outlook for that community, you have to question: what are our students looking like, are they getting a good education, are they getting adequate housing, are they getting good jobs? These are things we need to be addressing at the same time, and for me, this report I hope will push people to have the conversation and also to do drastic things.”

Savin Hill was the only Dorchester area listed as having an incarceration share lower than that of its population share – 1.6 percent to 1.9 percent, respectively.

Other villages with visibly fewer incarceration rates were not included in the report because of census sub-neighborhood boundaries, said Benjamin Forman, research director of MassINC and one of the report’s authors. Areas like Neponset and Columbia Point are not included in the neighborhood breakdown. Neither is the Ashmont area, which sees high rates of incarceration but has fuzzier boundaries that make population estimates imprecise, Forman said, noting that is a weakness in the data, mostly because it prevents them from clearly measuring the impact of incarceration rates in those areas.

“There’s no way we’re going to be able to make those communities strong if we don’t get to the root of the problem there,” he said.

The Council of State Governments Justice Center is working on refining policy recommendations to reduce incarceration and recidivism rates. While working sessions on the report will continue through the year’s end, the center expects to present a bill to the Legislature in 2017.

Topics: