June 8, 2016

Dorchester is home to 17% of Boston’s pre-1978 housing stock, but it contained a disproportionate number of the city’s lead poisoning cases – 36% – between 2009-2013, according to the state Bureau of Environmental Health. Cole Rosengren photo

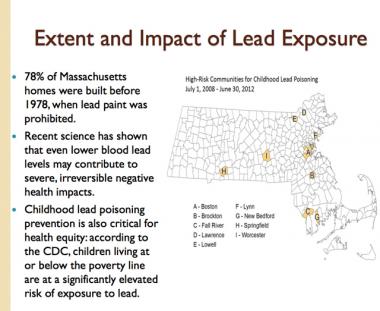

Boston still ranks among the state’s highest-risk communities for childhood lead poisoning, but that ranking is not due to a lack of funding, city officials say.

Since the early 1990s, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development has given Boston more than $34 million in lead abatement funding. Cases of elevated blood lead levels in children under six - the most vulnerable age group - have decreased dramatically during that period. Yet any housing built before 1978 – the year lead paint was banned – could still be a risk as paint is the primary source of most childhood lead exposure.

The city says its biggest challenge now is raising awareness and answering questions about perceived financial burdens of doing the necessary work. “We’ve got money, we’ve got help, it’s affordable, and we have capacity,” said Lisa Pollack, director of public relations for the Department of Neighborhood Development.

The Lead Safe Boston program offers forgivable loans of up to $8,500 per unit for eligible property owners; a state tax credit of $1,500 is also available. In each case, city specialists will walk applicants through the paperwork and construction process. Residents can also take certification courses to do basic work themselves.

Despite all of these resources, state data ranks Dorchester first among all Boston neighborhoods with 36 percent of incident cases in the city between 2009 and 2013. Mattapan accounted for 6 percent of the total cases in Boston.

The problem is broader than the stark numbers. Children who are never exposed to lead can be affected negatively because some landlords of non-compliant properties refuse to rent to families with children in the first place. This practice is illegal, but common.

Professor William Berman, the director of Suffolk University’s Housing Discrimination Testing Program, said that a fear of the unknown is often the driving factor for landlords of houses with lead-paint issues. A lack of education among real estate brokers is an issue as well.

Lead Paint

Lead Paint

“The problem is there’s a relatively significant financial incentive for people to discriminate,” said Berman. “They just don’t want to deal with it and they’re not quite sure what they’re facing.”

Even with available government money, the process can be time-consuming and more expensive than funds will cover.

John MacIsaac, president of locally based ASAP Environmental Services, said in an interview that property owners have a variety of options when it comes to lead abatement and they can vary widely in price. In many cases, the immediate lead hazard will be abated, but not permanently. For example, a door might be scraped or sealed but not removed.

“We’re not trying to make Dorchester lead-free. That would be nice,” said MacIsaac, “but it’s not realistic. We’re trying to make it lead-safe.”

Davida Andelman, former director of the Lead Action Collaborative and a longtime health professional, told the Reporter that the distinction between lead-safe and lead-free is at the heart of the issue. A property certified as lead-safe years ago may no longer be in compliance as lead paint can become re-exposed over time, especially if major work is done on the building by un-certified contractors.

Ideally, Andelman says, city funds should cover all owners of pre-1978 homes, even if children aren’t currently living there. “At some point in time there will be a family that has kids under the age of six, so just do it now,” she added.

City funding is only available now to owners who plan to rent to low- and moderate-income families or to give preference to families with children under the age of six. Officials will be continuing a campaign to spread awareness about these funds at community meetings and neighborhood events throughout the city.

Legislation proposed by state Rep. Jeffrey Sánchez of Jamaica Plain could also help change the conversation. Under his bill, discrimination penalties would be increased, the state tax credit would be raised to $3,000, and definitions of blood lead levels would be updated to align more closely with modern research.

Even with all of these programs and developments, everyone involved with lead-paint issues agrees that one of the most important things is to make sure people know that lead poisoning remains an ongoing issue.

“People think lead is dead,” said Andelman. “Lead is not dead.”

Topics: