October 29, 2008

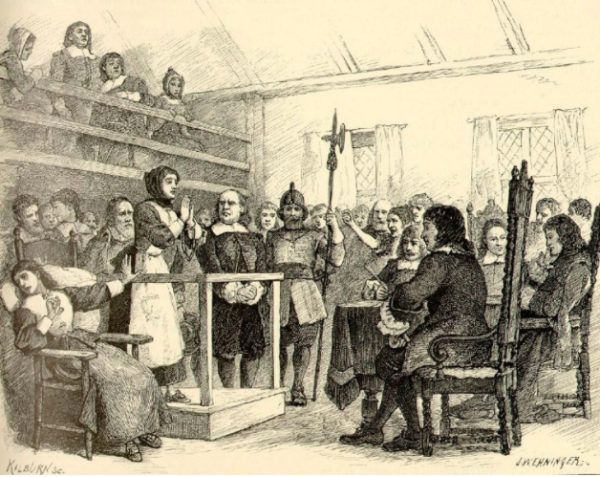

Illustration of the trial of Martha Corey, a wife of a Salem Village farmer who was convicted of witchcraft during the Salem Witch Trials of 1692. Illustration by John W. Ehninger in The Complete Poetical Works of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Houghton/Public Domain

Every year around this time, the town of Salem, MA observes a rather macabre part of their local history as they mark the executions of 14 women and five men, all accused witches, that occurred there over several days in 1692.

But decades before Salem began its bloody purge, Dorchester was the site of an apparent "witch" execution.

In 1648, eighteen years after Dorchester's first English settlers arrived, Alice Lake was arrested right here in Dorchester for witchcraft and, according to historical documents recently uncovered by a distant relative, was executed.

The story behind the story begins with a part time genealogist in Winnetka, California named Sean Wilson, who contacted the Reporter in 1997. Mr. Wilson, who makes part of his living tracing family histories for others, had set out on a search of his own roots, just around Halloween time. Like most people, Mr. Wilson had always believed that Salem was the birthplace of the witch hunt in America.

"Every year I'd see on the news, they'd be talking about Salem and really hyping it up," says Wilson. "I happened to have a note that one of my ancestors was accused of being a witch and executed. I decided to dive into it last Halloween when I saw all the footage."

When Wilson consulted some source books that included a family history of one of his lines, the Lake family, he struck a gold mine. In one study of families in Rhode Island, he found that one of his ancestors, Henry Lake, had come to Dorchester from Chidwell, a parish near Riverpool in Lancashire, England.

"He married Alice," says the author. "His wife was arrested for witchcraft. She must have been executed after 4 June 1648."

Digging deeper, Mr. Wilson next consulted a copy of The American Genealogist by G. Andrews Moriarty. In that work we find the most compelling evidence that Alice Lake was in fact executed for witchcraft in Dorchester. In referring to Henry Lake, the study says that "His wife was one of the earliest victims of witchcraft mania in New England."

The American Genealogist goes on to mention a correspondence from Nathaniel Mather, a minister in Dublin, Ireland to his brother, Increase Mather, in Dorchester that is dated 31 December 1684. Increase and Nathaniel Mather were the sons of Richard Mather, who was pastor of Dorchester's First Parish Church on Meetinghouse Hill until his death in 1669.

In that letter, Nathaniel asks his brother why he did not mention a certain incident in Dorchester in a book he had recently written.

Nathaniel writes: "Why did you not put in the story of ... H.Lake's wife, of Dorchester, whom, as I have heard, the Devil deceived by appearing to her in the likeness and acting the part of a child of hers lately dead on whom her heart was much set."

Nathaniel, the American Genealogist suggests, had left New England prior to March 23 1650, so Alice Lake "must have been executed" sometime before that. We can only assume that Nathaniel had first hand knowledge of Alice's execution.

One other vital piece of evidence from the American Genealogist: "Dorchester town records," it reads, "under the date of 12 (11) 1651, stated that it was agreed with 'brother Tolman' to take care of Henry Lake's child..."

Henry Lake, we are told in both sources, left Dorchester after his wife's execution, and must have left the care of a remaining child to his brother, Tolman. Henry left for Portsmouth, Rhode Island, where his branch of the family flourished, while other Lakes remained and are buried in "the old burial ground at Dorchester," according to one family history. However, questions remain about the last resting places of the Lakes, since no Lakes are listed in the roster of persons buried in Uphams Corner's Old North Burying Ground.

Earl Taylor, president of the Dorchestrer Historical Society, points to another important source. A book entitled A Modest Enquiry into the Nature of Witchcraft, written in 1702 by John Hale, makes the following reference to the Lake incident.

"Another [Alice Lake] that suffered on that account some time after, was a Dorchester woman. And upon the day of her execution Mr. Thompson minister at Braintree, and J.P. Her former master took pains with her to bring her to repentance. And she utterly denied her guilt of witchcraft; yet justified God for bringing her to that punishment: for she had when a single woman played the harlot, and being with child used means to destroy the fruit of her body to conceal her sin and shame, and although she did not effect it, yet she was a murderer in the sight of God for her endeavors, and showed great penitency for that sin; but owned nothing of the crime laid to her charge."

The Hale book indicates that Alice was the mother of four young children at the time of her death.

For Sean Wilson, though he admits it's a great conversation piece, it's frustrating not knowing the reasons behind his ancestor's demise. He surmises from Nathaniel Mather's letter that Alice had lost a young child, a common occurrence in the settlement, and that her grief was misinterpreted as witchcraft. Wilson hopes that further investigation will uncover questions to many more of his questions.

One thing is fairly certain: It is likely that if Alice was executed, she was hung, rather than burned. Common punishment for witchcraft in colonial America was hanging.

Another fascinating part of the Dorchester connection is the role of the Mather family. Richard Mather served as pastor of the First Parish Church from his arrival in Dorchester in 1635 until his death in 1669, and it is likely that he could have been involved in a case involving witchcraft in the community. His grandson, the famous minister Cotton Mather, played a key role in the persecution of the Salem trials in 1692. Is it a mere coincidence?

Not according to Sean Wilson, who believes there may have been many other witch executions in Dorchester in the years leading up to Salem.

"The phenomenon started, in my estimate, in the heart of Boston," says Wilson. "I think that Dorchester is really the heartbeat of the whole thing."

A version of this article first appeared in the October 30, 1997 edition of the Dorchester Reporter.

Tags: