February 16, 2012

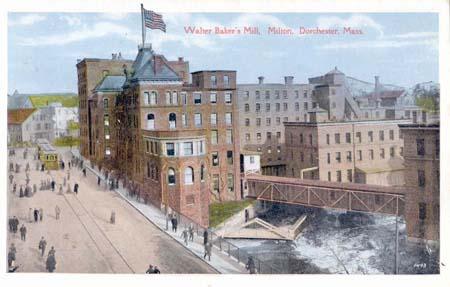

Chocolatier to the World: The Walter Baker factory in Lower Mills in its heyday. Postcard courtesy Earl Taylor, Dorchester Historical Society

Editor’s Note: This Sunday, the Dorchester Historical Society will host its Great Chocolate Cook-off— featuring a tasting contest and a look back at the historical roots of chocolate production— both here in Dorchester and beyond. Sunday’s event starts at 2 p.m. at the DHS headquarters, 195 Boston Street. Those participating in the cook-off should deliver their creations by 11 a.m.

The following are excerpts taken from an article by Peter F. Stevens originally published in the Reporter in 1998.

In the fall of 1764, Dr. James Baker smelled an opportunity along the Neponset River. A mouth-watering, money-making product - that was what materialized that autumn in Baker’s chance encounter with down-on-his-luck Irish immigrant John Hannon.

Baker, a Harvard graduate who had practiced “physicke [sic.],” medicine, for a time and had run a Dorchester store, met Hannon on a local road and soon discovered that even though the Irishman did not have a shilling in his pocket, he did possess a prized skill.

John Hannon knew how to make chocolate, for which colonists were willing to part with steep sums. And even after paying for the pricey product, imported from the West Indies, people had to “work” for their “fix” by grinding chocolate with mortar and pestle or with cumbersome, expensive “hand mills.”

Most significantly for Baker, the Irishman not only knew how to make the “sweet stuff,” but also how to set up and run a chocolate mill. But he was not in the business for the long haul, just for a quick and lucrative profit. Baker, once he had determined that the Irish immigrant knew the chocolatier’s trade, staked both savings and energy on the venture, which he hoped would prove long-term.

In the spring of 1765, Hannon was ready to put the plan to the test by grinding cocoa beans between two massive circular millstones. Now, his Dorchester partner would learn whether the Irishman knew his craft or had sold him a proverbial bill of goods.

Hannon set the top millstone to one third, the speed used to grind corn.

As the stone groaned and began to spin, he poured cocoa beans into a hole cut through the stone’s center. Then, the Neponset’s flow set the bottom stone whirling, and the motion of both “wheels” pulverized the beans into a thick syrup. The Irishman and Baker poured the liquid into a giant iron kettle and then into molds, where the concoction cooled to form chocolate “cakes,” more like “bricks” in weight and consistency.

With that first batch, Hannon proved that he could deliver the goods. America’s first bonafide chocolate factory had been born along the banks of the Neponset River in Dorchester.

Baker and Hannon were soon hard-pressed to keep up with sweet-toothed neighbors’ demands for the duo’s “hard cakes.” Sold under Baker’s name and advertised in Dorchester, Boston, and beyond in handbills, the chocolate was intended to be scraped by customers and boiled in water to make heavily sweetened cocoa.

Rising orders compelled Baker and Hannon to move the operation in 1768 to a larger space on the Neponset, Baker renting a fulling (cloth) mill from his brother-in-law, Edward Preston. Preston, however, was not satisfied with merely being the chocolatiers’ landlord. He had his eyes on the business - literally. For the moment, he appeared “interested” in only a curious fashion, but all that would change.

In 1772, Baker, with sales continuing to swell, opened a second Dorchester mill. Speculation that he and Hannon, who continued to operate the other plant, had quarreled and had either parted ways or forged a looser partnership, abounded. Baker had learned much from the Irishman: the new mill turned out nearly nine hundred pounds of chocolate in 1773.

With the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1775, the Dorchester chocolate-makers struggled to stay in business. Their dependence upon cocoa from the West Indies forced the pair to smuggle shipments of beans through the web of Royal Navy warships prowling the eastern seaboard.

In 1779, Hannon reportedly vanished on a voyage to buy beans in the West Indies. No one in Dorchester ever again saw or heard from him.

Baker was soon enmeshed in legal wrangles with Hannon’s “widow,” who seemed intent on running her husband’s mill with his capable apprentice, Nathaniel Blake, as her workhorse. Blake, deciding that Mrs. Hannon was running the business into the ground, walked out on her. He had little trouble in finding a new post - with James Baker.

In the 1790s, James Baker, the Harvard doctor and businessman who had launched America’s first permanent and profitable chocolate factory, stepped down after nearly four decades as “the king of cocoa.” He chose his son Edmund as the successor to run the family business.

Edmund expanded sales from the Northeast to the western outposts of the young republic’s widening borders. But in 1812, America’s second war with Britain suddenly heaped upon him the same shipping problems his father had suffered during the Revolution. This time, the Royal Navy’s squadrons choked off cocoa shipments so effectively that the kettles and molds inside the Baker chocolate mill stood virtually empty for two years.

Still, Edmund Baker’s prescience in expanding into the grain and cloth industries kept the family’s finances afloat, and, in an impressive act of faith that the aroma of chocolate would again waft above and along the Neponset, he tore down his chocolate mill to build one bigger and better.

Having taken the chocolate business to new heights, Edmund Baker entrusted the company to his son Walter. One of Walter’s first gambits was to expand his work force. In a sign of the changing times in the nation, two of the Dorchester businessman’s hires were young women, Mary and Christiana Shields, who walked onto the plant floor in petticoats in 1834. By 1846, Baker’s payroll included several women.

The Baker workers made their boss the first name in American chocolate. Such success also led to tough competition from two chocolate-making interlopers. By 1835, the Preston mill rolled out 750 pounds of the product a day. The Neponset featured a third chocolate competitor, Webb & Twombley, by 1842. The scent of chocolate permeating the area led locals to call the site “Chocolate Village.”

The pressure to fill endless wagonloads of “brown gold” was acute for Baker and his Dorchester rivals alike, for, with refrigeration for chocolate products nonexistent, the millstones ground to a halt in summer. Finally, in 1868, the advent of refrigeration turned the Chocolate Wars into year-round “combat.”

Walter Baker died in 1852, before the family could reap refrigeration’s benefits to the business. His passing marked the end of the Bakers’ hegemony in the chocolate business, which they had ruled for nearly ninety years. They had profited, persevering in the face of war, cut-throat competition, embargos, recessions, and fires. Although other men would run the company, the Baker name and the outfit’s logo would endure.

The Baker Chocolate Factory continued to turn out its near-legendary products along the Neponset until 1965. In that year, two centuries after a Dorchester doctor and shopkeeper and an Irishman set their first two millstones into motion, General Foods, Baker’s parent outfit since 1927, shut down the venerable red-brick plant and moved the operation to Dover, Delaware.

It is in the annals of Dorchester, not Dover, or anywhere else, that the proud legacy of Baker Chocolate truly lives on. For Dorchester was the site of America’s first successful chocolate mill, where Dr. James Baker and John Hannon turned cocoa into cash.

Villages: