October 28, 2010

Aaron Larget-Caplan: Group home next door was source of frustration in Uphams Corner.First of two parts.

Aaron Larget-Caplan: Group home next door was source of frustration in Uphams Corner.First of two parts.

Charles Hollins is accustomed to dealing with skeptics as he goes about his business of persuading residents that there will be no problems when his company, Bay Cove Human Services, locates a group home for either the developmentally disabled or those in need of psychiatric services in their neighborhood.

And he’s good at his job as director of advocacy; Bay Cove, one of the largest social services providers in Massachusetts, operates 19 such homes in Dorchester and 31 more throughout the city, according to an independent human services accreditation firm.

But the response that Hollins received at the Cedar Grove Civic Association several years ago still leaves him shaking. The outcry from residents over Bay Cove’s plans to locate a residential facility for six developmentally-disabled people in a nearby home was intense, reaching its peak when one father held his toddler over his head and asked if the child would be safe living in the neighborhood.

The neighborhood’s concern was hardly a surprise; residents are often anxious when a residential facility filled with people who have psychiatric problems, or are developmentally challenged, or are recovering from substance abuse, or are homeless is being planned for their neighborhood.

“There’s always going to be some hesitation, maybe even initial resistance,” Hollins said in a recent interview. “But once we tell them what we’re about and the degree of care and caution we operate with, people are willing to accept us.”

While Hollins said that Bay Cove, like other providers, works hard to gain neighbors’ acceptance on the facilities’ social value, it is the homes’ pledge that they will properly supervise and care for their residents and be strictly overseen by the state that allays concerns in the end.

Bay Cove’s pledge that the home would be constantly supervised was not persuasive for the people of Cedar Grove. A day after the contentious meeting with the neighborhood association, Hollins found that someone had thrown a volley of eggs at the house that Bay Cove was considering converting into a residential home for people with developmental disabilities. A short time later, the company abandoned its plans for locating the home in the neighborhood.

The Cedar Grove experience remains the only time that Hollins, who has been with Bay Cove for eight years, can remember the company abandoning an effort to locate a home for either the developmentally disabled or in need of psychiatric services anywhere in the state. Bay Cove CEO Stan Connors said he can recall only one other backing-off instance in his 32 years with the company.

“Only by showing them that our homes will be safe and supervised will we welcomed as good neighbors,” Connors said.

State Rep. Martin Walsh, a Democrat who represents parts of Dorchester, said while he was pained by some of the overzealousness of the Cedar Grove neighborhood, he understood their frustration. “Many in Dorchester feel that they are overburdened by the presence of so many such group homes,” Walsh said. “I know I feel sometimes that we are overburdened.”

Yet, a six-week investigation by the Reporter found that 12 of the group homes that exist in Dorchester – those that provide residence and services to people with psychiatric conditions – are allowed to go unsupervised for some periods of time during the day. Although state mental health officials said they were confident that neither those residing in the homes nor neighbors has ever been at risk, a neighbor of one Uphams Corner group home had to seek the assistance of his neighborhood association during the summer following a year-long struggle to gain the attention of the home’s supervisor.

Rep. Walsh is a member of the Joint Committee on Mental Health and Substance Abuse, and has long been regarded as an advocate for those in need of such services. In an interview he said that while he has never done an actual count on their number, he believes that Dorchester has a larger proportion of residential homes providing round-the-clock counseling, care, and/or other services to the developmentally disabled, those in need of psychiatric care, the homeless, or people with substance abuse problems than other Boston neighborhoods.

A precise count comparing Dorchester with the other neighborhoods is impossible to obtain from official records. While the locations of group homes for the homeless and for people with substance abuse problems can be identified, the whereabouts of residences for people with developmental disabilities or severe mental conditions cannot. The state Executive Office of Health and Human Services, which oversees the homes’ providers, is prohibited by federal law from revealing those locations because of concerns about the privacy of their residents.

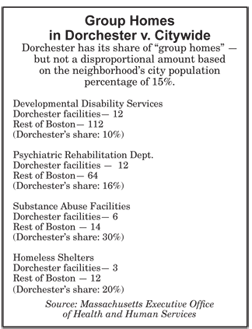

Group homes: Dorchester v. citywideHowever, after polling the providers of homes for the developmentally disabled and those in need of psychiatric services, the Reporter found that the percentage of group homes in Dorchester is about commensurate with its percentage share of the city’s population. To be specific, Dorchester is the city’s largest neighborhood and its nearly 100,000 residents constitute 15 percent of Boston’s population. Of the 235 residential homes for developmentally disabled, those in need of psychiatric services, the homeless, or former substance abusers that are located throughout the city, 33 of them (or 14 percent) are in Dorchester.

Group homes: Dorchester v. citywideHowever, after polling the providers of homes for the developmentally disabled and those in need of psychiatric services, the Reporter found that the percentage of group homes in Dorchester is about commensurate with its percentage share of the city’s population. To be specific, Dorchester is the city’s largest neighborhood and its nearly 100,000 residents constitute 15 percent of Boston’s population. Of the 235 residential homes for developmentally disabled, those in need of psychiatric services, the homeless, or former substance abusers that are located throughout the city, 33 of them (or 14 percent) are in Dorchester.

Overall, the Reporter found that about 600 individuals reside in the group homes in Dorchester, about half of them in the three facilities for the homeless that are located in Uphams Corner. Under state law or contracts with the providers, around-the-clock supervision is required at the homes for people with developmental disabilities, those being treated for substance abuse, and the homeless. But such is not the case at the 12 or so facilities that provide housing and care for those with psychiatric problems in Dorchester.

Marcia Fowler, deputy commissioner for mental health services for the Department of Mental Health (DMH), said homes for those with psychiatric conditions do not need to have a manager on site during those daytime hours when all of the residents are out of the house at work, perhaps, or at a counseling program, or when residents have achieved “home alone” status, which means they have been psychologically stable for an extended period of time.

“We monitor this very closely,” Fowler said. “Proper supervision is maintained at all times. But there are times during the day when no supervisor is needed.” These homes are always staffed during the nighttime hours to ensure safety, Fowler said, adding that they are also routinely inspected. None of the homes in recent memory has lost its license or even been disciplined for failing to provide adequate supervision of residents, she said.

Rep. Walsh said he was surprised to hear that some residential homes for those with psychiatric conditions may not have staff on site during the day. “One of the principal selling points is that these facilities are going to be providing constant care and supervision,” said Walsh. “If there’s a problem inside or outside, neighbors have to know that there’s someone always there.”

However, a couple who had bought a house in Uphams Corner a year ago complained recently that they had been regularly frustrated in trying to gain the attention of the supervisor of the group home located next door to them in an effort to resolve their problems with some of the residents of the home.

Aaron Larget-Caplan said that he and his wife were frequently disturbed by the loud commotion coming from the 15 or so residents of the group home. He said his aggravation with the noisemaking, excessive smoking, loud coughing, and, on occasion, public urination was heightened when he was unable to find any supervisor at the home to complain to. “I would call and get no answer, and then go over and knock on the door and no one would answer, so I wound up eventually calling the police as a last resort,” Larget-Caplan said.

Finally, he took his complaints to the Uphams Corner West Side Neighborhood Association, which sought a meeting with officials from Vinfen Corp., operator of the group home. That September meeting and a later one finally brought relief to Larget-Caplan: Vinfen has constructed a six-foot fence between his home and the facility, reducing the noise and cigarette smoke that has aggravated him and his wife. In addition, Vinfen has — temporarily, at least — added a second staff person at the house during the day to ensure that the home will never be unsupervised.

However, Larget-Caplan said he was concerned to learn at the meeting that neither Massachusetts law nor Vinfen’s contract with the state requires the company it to staff the house with a supervisor at all times.

“With supervision, our only requirement is to make certain that those residing at the home are safe and provided for,” said Jon Murphy, director of mental health services for Vinfen in Massachusetts. The supervisor can leave the home unattended during the day, Murphy said, as long as the home is unoccupied or those residents who are there have been determined to be sufficiently stable over a long period of time to have “home alone” status.

Murphy said the state Department of Mental Health, which oversees residential facilities for people in need of psychiatric rehabilitation services, had determined that Vinfen had supervised its residents properly and had dealt with Larget-Caplan’s complaints in a proper fashion.

Vinfen operates a total of 32 mental health facilities in Boston – 14 for residents in need of psychiatric rehabilitation services, like the home in Uphams Corner, and 18 for people with developmental disabilities. Five of the homes, with a capacity of 37 residents, are located in Dorchester.

The state pays for the operation of all group homes – those providing services to people with developmental disabilities, to people in need of psychiatric services, to substance abuser, and to the homeless.

While the state could not provide a breakdown as to what it pays to Vinfen and Bay Cove, its two principal providers of residential services for those with psychiatric problems, for the homes they operate in Boston or Dorchester, the state spends more than a third of the $621 million it pays for such care to all providers on “community-based” programs, including group homes, Fowler said.

Around-the-clock supervision is mandated by the state Department of Public Health at the residential homes that treat substance abuse. In Boston, there are 20 such facilities serving more than 550 individuals. As with mental health homes, Dorchester has the most of any city neighborhood, six homes with a current capacity of 139.

The state pays the homes $75 per day for each individual residing at a group home that deals with substance abuse. At that rate, the private companies that operate the 20 homes throughout the city are being paid a maximum of $15 million for providing their care, with $3.8 million of that sum is going to run the six homes in Dorchester.

In all, the state pays $130 million a year to maintain these residential homes throughout the state. To maintain optimum performance at the sites, the Department of Public Health inspects the operations of all licensed facilities within six months of their commencing operations, and every two years after that, said Hilary Jacobs, DPH’s acting deputy director of the Bureau of Substance Abuse.

The inspections ensure that the homes are meeting all state requirements that the residents be housed in safe environments and receive mandated levels of treatment, Jacobs said. However, two of the homes operating in the city of Boston were closed during the past year, unable to maintain the standards expected by the DPH, Jacobs said.

A program run by the Salvation Army was closed after the state found it was not meeting “minimum treatment requirements,” according a Public Health spokeswoman. And a program for women with substance abuse run by HRDI closed because it failed to provide the access to care that was called for in its contract with the state, the spokeswoman said.

“We are intent of maintaining the standards,” said Jacobs. “We are vigilant in maintaining the standards.”

NEXT: A focus on sober homes located in the neighborhoods.

Stephen Kurkjian is the Senior Investigative Fellow and Pat Tarantino is a reporter at the Initiative For Investigative Reporting in the School of Journalism at Northeastern University. Their work for the Dorchester Reporter is funded by grants from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and the Ethics and Excellence in Journalism Foundation. The foundations are committed to supporting investigative and watchdog journalism by community news organizations in the Boston area.

Stephen Kurkjian can be reached via e-mail at stephen@dotnews.com, and Pat Tarantino can be reached at pat@dotnews.com.

Topics:

Tags: