October 31, 2024

Last week, Mayor Wu and four major business groups struck a compromise that would increase property taxes for both residential and commercial owners in Boston and avoid a significant increase only for homeowners.

In a statement announcing the deal, Wu’s office said, “the proposal allows for a modest modification to the current tax system with clear guardrails to prevent too great of a burden from being placed on commercial taxpayers.”

The agreement would cap the commercial tax rate at 181.5 percent for fiscal year 2025 before incrementally decreasing it throughout the next two fiscal years to its current level of 175 percent. Her office previously said that without a plan, residents in an average single-family home would face a quarterly tax hike of 28 percent in January.

The deal reached last week would allow the city to fund its $4.6 billion budget without any spending cuts.

A disconcerting trend

Boston is facing challenges funding its budget because of a divergent trend regarding property values. According to preliminary estimates by City Hall, overall residential property values rose by 4 percent while commercial values declined by 7 percent.

The impact on the budget is particularly severe because Boston relies on property taxes far more than any other major US city. Property taxes currently account for about 72 percent of the city’s revenue. Businesses contribute 58 percent to the property tax revenue while residential owners come up with the remaining 42 percent.

A recent analysis by the Pew Charitable Trusts showed that Boston had the highest reliance on property taxes as a percentage of revenue in 2020 among 10 major cities like Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia. For half of the cities in the study, property taxes generated only about 32 percent of revenue. Boston was the outlier: 67 percent of its budget depended on property taxes in 2020.

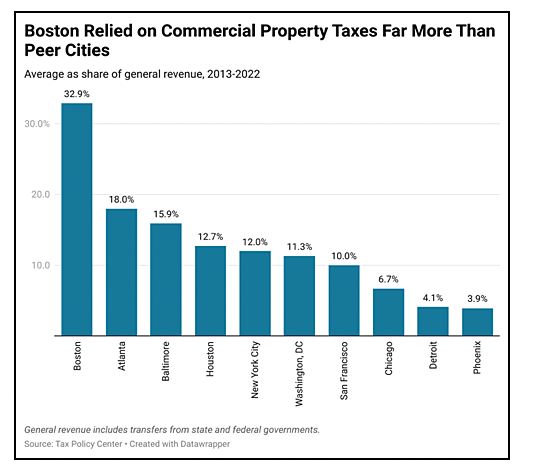

In another study by the Tax Policy Center, researchers analyzed how 47 major cities relied specifically on commercial property taxes between 2013 and 2022. The results again showed that Boston relied far more on revenue from commercial taxpayers than any other city. A third of the city’s total revenue depended on commercial property taxes. It was far above the average reliance on commercial property taxes in Houston (13 percent), New York City (12 percent), and Washington, DC (11 percent).

Given how much Boston relies on commercial tax revenues, a drop in real estate values would, therefore, have significant impact. A report from the Center for State Policy Analysis at Tufts University estimated that the city will face a $1.2 billion to $1.5 billion revenue shortfall over the next five years. The report, which was funded by the Boston Policy Institute, warned that “this is not a short-term challenge but the arrival of a new normal.”

Remote work, rising office vacancies

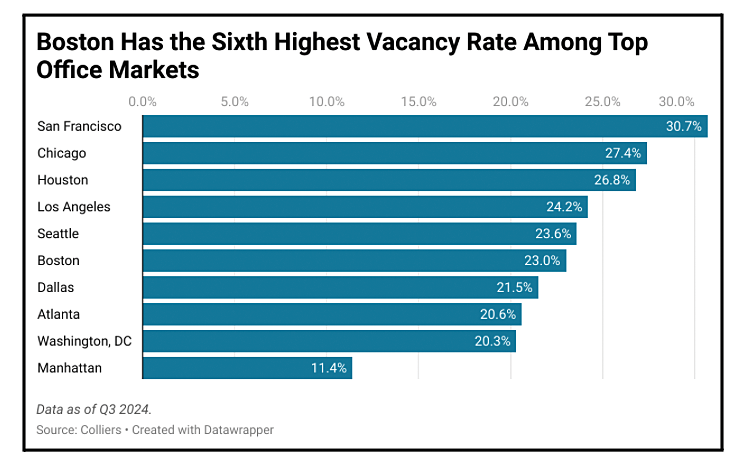

One of the main reasons commercial property values have declined in Boston is because companies have pulled back on their need for office space as employees continue to work remotely. The vacancy rate in the Boston metro area was 23 percent in the third quarter of 2024, according to a report by Colliers, a commercial real estate service firm. The average national rate was 17.7 percent.

The vacancy rate across the past few quarters in Boston has reached record levels, says Jeffrey Myers, research director at Colliers.

“And that doesn’t matter whether you’re talking about the Class A top end of the office market, or the Class B or modest end of the office market. Landlords across the spectrum have really had to deal with the highest vacancy rates that we’ve ever had on record,” he said in an interview.

The situation in Boston is not unique, Myers indicated. “I think that the decrease in commercial property values is something that’s being experienced across the country.”

Other cities and lower office demand

In New York City, office buildings account for 21 percent of all property taxes. Last year, the city’s comptroller investigated four scenarios that estimated how a decrease in demand for office space may impact the city’s budget. In the “doomsday” scenario, the value of the office market would drop by 40 percent and lead to a budget shortfall of about $322 million in 2025 and $1.1 billion in 2027.

The highest vacancy rate is currently in San Francisco, where about 31 percent of office spaces are empty. Last year, 10 percent of the city’s budget relied on tax revenue from commercial properties.

In a recent study, Capital Economics, an economic research firm, described the city’s office market as having “the poorest outlook.” Its findings predicted that property values will drop by over 40 percent between 2023 and 2025.

San Francisco’s Controller, in an analysis of the city’s proposed budget, noted that remote work as well as high interest rates “continue to have significant impacts” on property taxes.

One positive indication from the quarterly office market report that Myers authored about Boston is that office demand is trending upwards. However, Myers is cautious about the finding.

“It’s trending in the right direction, but we’re starting from a very low point,” he says. “And trending in the right direction doesn’t mean you’re necessarily growing. It could be just you’re shrinking less slowly.”