October 26, 2023

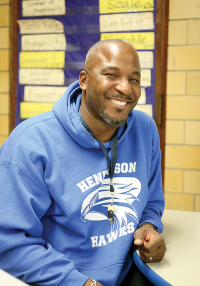

Former teacher Barbara Henry, center, with Connell Cloyd and several Henderson Upper staff members during Henry’s surprise visit to the school in September shortly after Cloyd had been announced as the winner of the award named in her honor. Seth Daniel photos

For award-winning seventh grade math teacher Connell Cloyd of the Henderson Upper School, the secret to reaching a tough age group in a subject like math is to be crazier than they are.

The 43-year-old Cloyd, a Memphis native who lives in Dorchester and has taught at the Henderson Upper for 13 years, laughed during a recent interview when he shared that he once jumped up on top of a school desk to show 12-year-olds his authentic enthusiasm for math.

Kids that age, he said, can sniff out a fake miles away.

“Everyone in middle school has the middle child syndrome,” said Cloyd. “You have to help them to understand it’s okay to be weird and awkward and that it’s just temporary.”

Despite that, he noted, “They still have a passion to learn even though they may give you attitude. On the flip side, I act crazier than they act, and they don’t know what to do with that.”

Cloyd is a popular teacher with current and former students whom he often sees around the neighborhood. “They remember me standing on the desk, and they know that I wasn’t lying about my excitement for math,” he said.

But his classroom skills have drawn attention beyond the neighborhood, landing him this year’s Barbara Henry Courage in Teaching Award, an honor bestowed on only one educator in the country.

Henry, who attended Girls Latin School in Codman Square and is from Boston, was recognized internationally in 1960 when she was the only teacher who would instruct Ruby Bridges – a young Black girl who desegregated New Orleans public schools. Henry, now in her 90s and living in Boston again, established the teaching award in 2021 and it has quickly gathered acclaim for its awardees.

After a difficult year at the Henderson Upper School with safety issues and other incidents, Henry picked up on the news reports and personally nominated him, Cloyd said.

“Out of nowhere [in September], Mrs. Henry walks into the Henderson building one day,” said Cloyd. “It still hasn’t really sunk in because you’re talking about a prominent figure in history. I was humbled and I didn’t know what to do … It feels good someone recognizes the things you’re trying to do and the sacrifices you’ve made.”

Growing up in Memphis, Cloyd experienced the lingering effects of the segregation that Henry and Bridges endured. Prior to living with his grandfather from the age of 12, Cloyd said, he underwent experiences no child should have to endure.

They caught up to him later in life. Despite being a go-getter who was always involved in math and science camps, as well as athletics, he acknowledged that he “harbored a lot of trauma from my younger years and I’d learned to hide it and mask it very well,” he said. “The things I was exposed to at an early age I had to succumb to or understand them. I understood them.”

A “life-changing” moment occurred when Phillips Andover Academy came to Memphis to recruit minority students for their school, and for a multi-year math and science summer program. Cloyd said he didn’t have anyone to push him to go for the school, but his guidance counselor insisted he at least participate in the summer program.

That brought him to New England every summer, and he fell in love with the region. That sparked him to stay at Phillips for a post-graduation year. He flourished there, joining the theater program as a stage actor, playing basketball, and running track.

Cloyd attended Tufts University in Medford so he could stay in New England. He found great success there in his sciences studies while also, on a whim, pursuing an improbable yet successful diving career.

But his years of trauma, and an up-to-then undiagnosed Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD), struck him head-on in his junior year. He pivoted from the sciences to education, where an “Intro to Child Development” class changed his life.

Cloyd said it was then that he began to understand himself and realize that he had serious issues he needed to address. “When I got with the elite of the elite in college, it wasn’t good enough anymore; the way I had coped caught up with me,” he said.

As he worked on healing and took education more and more deeply, he said an “epiphany moment” led him to the classroom. “I began to imagine how it would have been different for me if I had someone like me leading the way to help with all of these things,” he said. “I just came to the conclusion that I had to be a teacher. I had fought it forever…but I felt I had so much to offer. It was a calling.”

After a stint in Medfield and a teaching position at a Department of Youth Services (DYS) program, Cloyd was hired in Boston as the seventh grade math teacher at the Henderson Upper School in 2010, where he has been multiplying his impacts ever since.

“Kids this age can sniff you out and they can tell what you’re in it for,” he said. “If they can tell you’re in it for the job and to get a paycheck, they’ll be all over you. If they see you really want to teach them and care about that, they will buy in.”

Cloyd employs his own methods in the classroom, like using supermarket circulars as teaching tools, striving to have his students buy in to his view that math is an asset in everyday life. He also shares his personal story and how he overcame traumatic times. “I don’t sugarcoat it,” he says. “I tell my students exactly what happened to me in my life without forcing it.”

Living in Dorchester near the school has also helped him to bridge gaps in what can be a tough environment. Students often see him around the neighborhood, and many times he knows parents before they're kids.

“They see me and know I’m a real person and I live right here where they live,” he said. “One year many of my students lived right in my immediate community and always wanted me to come down and play basketball with them … It’s become very important in my relationship building.”

As for the Henry award and the publicity that he’s had, Cloyd said it won’t change his focus on his school community. “I just can’t see myself going anywhere else but the Henderson,” he said. “There have been opportunities, but I’m so rooted here, I can’t do it.”