October 4, 2023

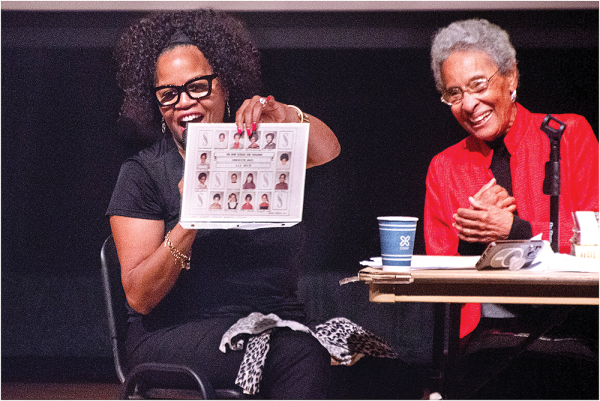

Kim Janey shows Gloria Lee and the forum audience her class picture from New School for Children in 1964. Chris Lovett photo

They marched, they protested, and they gathered detailed proof that the Boston Public Schools were racially separate and unequal.

When a stubborn school committee failed to acknowledge the problem and provide remedies, parents and activists organized one-day boycotts, carpooled, and raised money for student transportation to more adequate schools. They even opened their own “freedom schools” to surmount barriers of low expectations.

These were the actions taken by people in Boston’s Black community between 1963 and 1974, a period of more than ten years before school desegregation was ordered by Judge W. Arthur Garrity in response to a federal lawsuit filed by Black parents in 1972.

Overshadowed by the turmoil and strife that came after the ruling, that earlier history took the spotlight in a forum last month at Roxbury Community College sponsored by the Boston Desegregation and Busing Initiative.

“This is a much different narrative from the one that has dominated over the last fifty years,” said one of the forum’s panelists, Zeb Miletsky, author of the recently published “Before Busing.” “Like all Bostonians,” he said, “these parents paid the city taxes and were entitled to a quality education for the children from its public school system, a constitutional right, something which they had been denied.”

That point was made to the Boston School Committee – with 14 demands for remedies – by leaders of the Black community. They included Ruth Batson, the Roxbury parent and co-chair of the Boston NAACP’s Education Committee, and Paul Parks, the other co-chair, an engineer and activist who would later become the state’s first African American Secretary of Education.

Batson’s presentation took place after years of advocacy, but little more than one month after shocking news reports around the world showed non-violent demonstrators against racial exclusion in Birmingham, Alabama, being attacked by police dogs. Many of the demonstrators were of school age, taking part in a “Children’s Crusade” against segregation. With its prominent roles for young adults and children, the civil rights campaigns in the south would resonate with parents and activists in Boston.

Little more than a month later, after threats in response to desegregation of the University of Alabama, President John F. Kennedy, in a televised speech, called for new laws on voting rights, educational opportunities, and access to public accommodation. The speech aired on the same night as the presentation to the Boston School Committee, and the night before the assassination at his home in Jackson, Mississippi, of the civil rights worker Medgar Evers.

During the Sept. 26 forum, the north-south connection was even more explicit when the audience saw an excerpt from the recent PBS documentary, “The Battle Over Busing,” in which longtime activist Hubie Jones — the dean emeritus of the Boston University School of Social Work — singled out the showdown with the school committee as the point when the civil rights movement came to Boston.

Speaking at the forum, Jones said that on arriving in Boston for post-graduate studies, he saw “patterns of discrimination” that ranged from Boston’s public schools and public housing to the police and fire departments, even to a dearth of Black people in jobs interacting with customers at downtown department stores. “And they were almost invisible as a presence in the city,” he said, “so I saw this as an ‘Up South’ place, and something had to be done about it.”

That something was an event that turned invisibility into a one-day work stoppage and a march to the Boston Common, converging on a memorial gathering for Medgar Evers. “And the presence was felt,” said Jones, “and the message was sent.”

In 1965, following repeated unsuccessful attempts to pass a racial imbalance law, Rev. Vernon Carter mustered a different kind of visibility: a vigil outside the Beacon Street offices of the Boston School Committee that began just a few days after the march from Roxbury to the State House led by Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. and lasted almost four months—until the legislation was signed into law.

Rev. Carter’s daughter, Vernita Carter-Weller, devoted most of her time as a panelist at the forum to reading from her father’s account of how the vigil went from a crusade of one to something much larger. “But,” she noted, “during those days, he was shot at, screamed at, assaulted, and reviled. At the same time, newspapers and news sources from not only Boston but from all across the country reported that thousands of people who came to walk with him, pray with him…”

Another panelist, Charles Glenn, was a desegregation planner who, according to Ronald P. Formisano’s “Boston Against Busing,” would later be a critic of plans put in place by Judge Garrity. Before he took charge of urban education and educational equity for the state in 1970, Glenn was a student activist at Harvard and then an Episcopal priest at a church in Roxbury. That led to contact with teenage civil rights activists in North Carolina, some of whom were invited to events with students in Boston.

For Roxbury teens with limited interest in events in the south, Glenn said, the meeting in late 1963 with the youthful activists from North Carolina was “absolutely galvanizing.” A few months later, when urban and suburban teens gathered for a freedom school at St. Cyprian’s Church in the South End, Glenn said he decided to have all the teaching done by teenagers. He also asked the students to write about what freedom meant to them.

“In my view,” he said, “they weren’t talking about what we call ‘civil rights.’ They weren’t talking about laws—they weren’t talking about that kind of thing. They were talking about the dignity of standing up as a human being and the way in which they saw that reflected in the great bravery of the youth they had heard from North Carolina, and which they intended to express in their own lives. And many of them did.”

Another panelist, Batson’s longtime assistant, Lyda Peters, had her own example of how an activist’s life of service could inspire a movement.

“And when you work with someone who has that kind of strength, they also spread that strength, and that’s where action comes from,” Peters recalled. “That’s the kind of thing that makes people know that they have a mission in life and that the mission belongs to someone else: it’s for you to do something for other people.”

That was the mission cited by Jean McGuire, a panelist who formerly served as a Boston School Committee member and executive director of METCO. In September of 1974, when the desegregation order took effect, McGuire was with Batson, riding the first bus taking Black students to South Boston.

The event’s moderator, former Boston mayor and city councilor Kim Janey, asked McGuire why she was on the bus. “We wanted to protect the children,” McGuire answered. “We felt that if we as adults were there on the bus that would make the families who trusted us know that we put our lives on the line with their children, that it would be safe.”

Almost fifty years after being visible on a bus, McGuire was calling for political visibility, repeatedly urging people to use their right to vote.

Along with community control, visibility in educational content was among the goals of freedom schools organized in Roxbury and Dorchester in 1966. Instead of learning materials in which Black presence was invisible or marginal, organizers of the schools wanted to include learning about non-violence, Black history, and civil responsibility.

One of their ventures, The New School for Children, was established when parents took their children out of the Gibson School in Dorchester, where a year-long substitute teacher, Jonathan Kozol, had been fired for teaching a poem by Langston Hughes. In his book “Death at an Early Age,” Kozol said the firing had been triggered by a complaint from a single white parent.

Gloria Lee, a panelist who had worked for METCO, had taken part in a “Freedom Day Stay Out” in 1964. At the forum, she spotlighted her place in history by displaying a class photo from The New School for Children.

When Janey saw the photo, she asked for a closer look—and saw a piece of her own history near the upper right corner: a little girl, crowned with an upright, voluminous Afro. She then showed the photo to the audience—as a documentation, a discovery, and a trophy.