October 7, 2021

Andrew Haile’s property on Millet Street has a garden comprising six apple trees, four pear trees, two fig trees, two plum trees, one mulberry tree, and, his latest additions, four pawpaw trees along the property’s wooden fence.

Take a look at Andrew Haile’s property, and it’s clear where his passions lie. The 36-year-old Northeastern professor’s yard on Millet Street west of Washington is brimming with a variety of trees that he has planted over the last three years. Nestled in his 5,000-square-foot yard is a garden comprising six apple trees, four pear trees, two fig trees, two plum trees, one mulberry tree, and, his latest additions, four pawpaw trees along the property’s wooden fence.

But Haile’s backyard is an exception across his neighborhood. Beyond his home, he said, the neighborhood is bereft of trees, save for a few freshly planted ones scattered throughout the area. The disparate spread of trees in the city as a whole is an issue that the Parks and Recreation Department is trying to address.

“The reality is that the tree canopy is not equitably distributed in the city,” said the Rev. Mariama White-Hammond, City Hall’s chief of environment, energy, and open space. “There are some neighborhoods that are leafy green and some neighborhoods that have lots of hardscape. … the tree canopy conversation is really about how we right these historical wrongs, and how we take seriously the health and well-being of every single resident in Boston.”

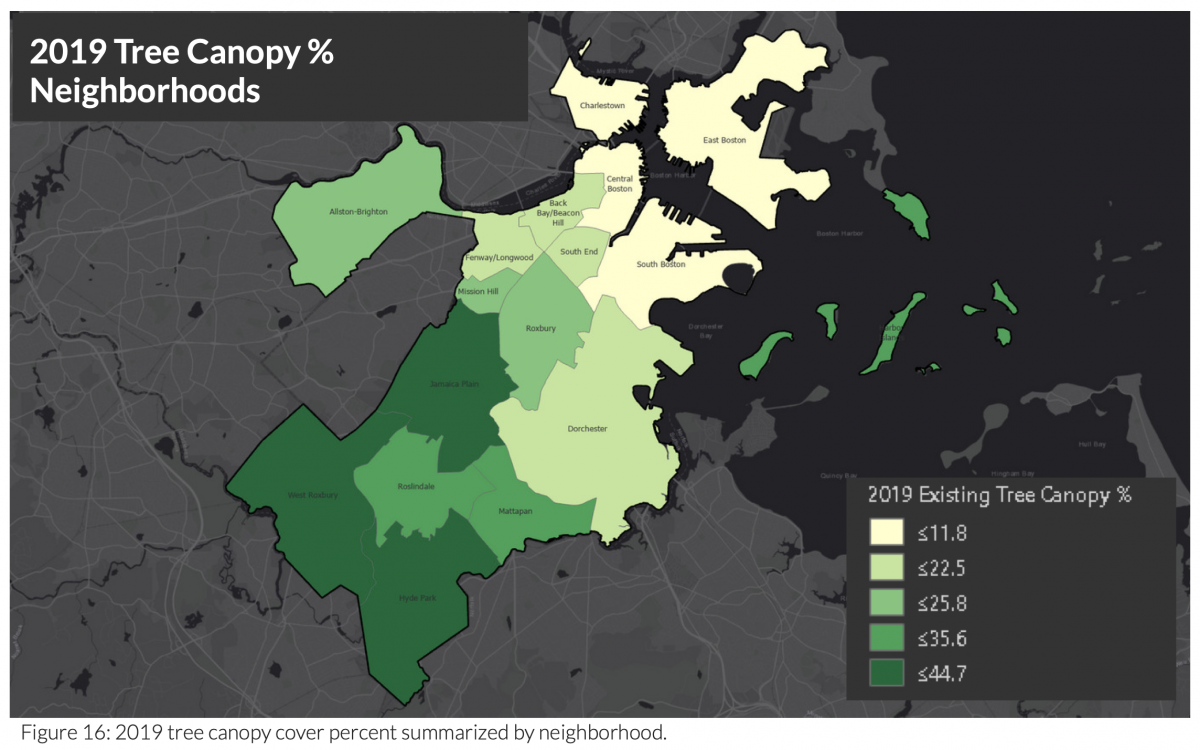

The Parks Department has mapped out the losses and gains in the so-called tree canopy – the percentage of land covered by trees – from 2014 through 2019. According to the report, total tree canopy coverage remained stable in the city over the six-year period, dipping from 26.6 percent to 26.5 percent.

The study narrowed in on where these slight losses occurred, and it showed that residential properties across Boston experienced the largest decrease in tree canopy coverage compared to nonresidential properties.

In Dorchester, close to 20 acres of tree canopy coverage were lost on residential properties—the highest loss of any neighborhood – but that decrease was offset by canopy gains on commercial properties, open spaces, and nonresidential lots.

As temperatures continue to climb due to climate change, White-Hammond said, planting more trees will become essential to combating the additional warmth. New trees could also prevent more areas in Boston from becoming “heat islands,” the term for urban spaces that are typically hotter than rural areas.

Above, Andrew Haile with a pear tree.

Residents who live and work in tree-starved neighborhoods are more likely to experience the adverse effects of the sun beating down on shade-less asphalt, including threats to their overall health and skyrocketing utility and electricity costs for air conditioning.

Without trees, White-Hammond added, residents will experience higher rates of asthma, an increasing number of hospital visits, and more cases of heat stroke, particularly for people who have to work outside.

“The ability to take a moment under a tree could be life-saving,” she said.

Some city neighborhoods are already experiencing the negative effects of lower tree canopy coverage. Chinatown comes to mind for White-Hammond as an area that has been particularly affected by a lack of leafy canopies. It has few trees to help clean the air of pollutants, she said, so it’s no surprise that children who grew up in Chinatown are experiencing higher rates of asthma.

The unequal distribution of trees can be traced back to the 1950s and 1960s, said White-Hammond, when so-called redlining – banks and loan companies refusing to give financial services to applicants based on where they live, areas that were said to be outlined in red – segregated potential home buyers by race. Where residential streets were lined with trees, the values of the homes were usually higher.

“If you look at redlining and what parts of the city were redlined and what parts of the city had heat islands and low canopy, there is a striking overlap,” White-Hammond said.

In Mattapan, its tree canopy has dropped nearly one percent over the last five years. On residential properties, close to 13 acres of tree coverage were lost, a change that Fatima Ali-Salaam, chair of the Greater Mattapan Neighborhood Council and a member of the Urban Forest Plan board, has seen happen. The community advisory board has roughly 50 members, including Millet Street’s Andrew Haile.

“Many trees that were on the street are no longer there, and you’ll see long stretches of it where there are no trees,” Ali-Salaam said.

She believes that replanting trees throughout the city is an urgent issue that, if addressed effectively, can help combat the impacts of climate change. Like the case in in Chinatown, Ali-Salaam said, an increasing number of residents in Mattapan are also experiencing asthma.

“We can’t keep going the way we’re going,” she said. “There is a price to pay, and it’s going to be our health.”

Though the Parks and Recreation Department plans to plant trees in the areas they’ve noticed have experienced the greatest loss, residents, taking their cue from Haile, can always plant the seeds for trees in their backyards.

Not to be left out of the conversation is the fact that trees – the survivors and the newly planted ones – add beauty to neighborhoods. “I think we form a bond with those trees,” White-Hammond said. “They tell the stories of our neighborhoods, and they’re a part of our neighborhoods.”

Right off Dorchester Avenue where White-Hammond lives, she had grown especially fond of a tree outside her home that bloomed pink blossoms in the spring. Before it was uprooted due to its declining health, she said, it used to shade the front of her home.

Over time, her neighborhood has gotten less green, and it’s now considered a heat island— a situation that has become even more unbearable since she lost her favorite tree.

Trees “look like they’re just standing there,” White-Hammond said, “but they’re really putting in work that we can’t do ourselves.”