March 25, 2021

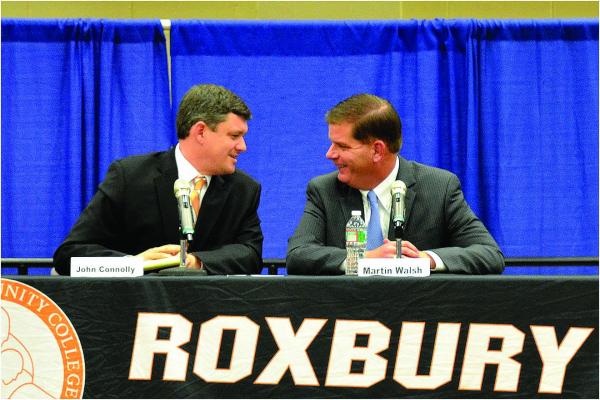

Rep. Walsh and Councillor John Connolly shared a lighter moment during a candidate’s forum at the Reggie Lewis Center in Roxbury. Walsh and Connolly prevailed in the city’s preliminary election in September 2013. Chris Lovett photo

In this edited excerpt from his campaign trail ebook “This Way to City Hall,” published after the 2013 mayoral race, former Reporter news editor Gintautas Dumcius describes the campaign’s last days as the two finalists faced off in November after clearing a 12-candidate preliminary.

In the weeks after the September 24 preliminary election, Marty Walsh and John Connolly crossed paths frequently as they were leaving and entering meetings with neighborhood and activist groups, often shaking hands and sharing hugs. They looked at each other, shared a smile and maybe thought, Can you believe it’s down to us?

They had run into each other numerous times during their respective climbs up the ladder of local politics. Six years apart in age, they first met at the State House: Walsh, a freshman state representative from Dorchester, and Connolly an intern on the House side of the Judiciary Committee, working for a West Roxbury state representative.

The Walsh and Connolly families were immersed in local politics. Walsh had heard talk of the labor movement and local campaigns at the dinner table, and he made trips to the Dorchester union hall as a child with his Uncle Pat. He would see the numbers 223, which denoted the laborers’ union.

“I didn’t know exactly what they meant at the time, but I knew I wanted to be part of it,” Walsh said. “As you can imagine, growing up in the Walsh household, those numbers led to a lot of discussions about the labor movement, about politics, and the importance of being involved.”

Connolly had seen public service through the eyes of his father and mother: Michael Connolly was first elected secretary of the Commonwealth in 1978, when John was five years old. Lynda Connolly, John’s mother and a Roslindale attorney, was active in politics herself and was appointed to a judgeship in 1997.

While they first met at the State House, Walsh and Connolly connected in a more personal way at a summertime gathering in Cape Cod in 1999 or 2000.

It was a Fourth of July party at the Timilty house. Walsh was the guest of Walter F. Timilty, the scion of another political family who had been elected to the House in 1999 as a state representative from Milton.

The party had a mix of politicos and Cape Cod locals. As everybody else began to dip into the available booze inside the home that night, Connolly remembers that he and Walsh, who was several years sober at that point, went outside and started to toss a Wiffle ball around and talk politics.

During that conversation, it became clear to both that the two of them would run for mayor someday. Each one had designs on City Hall’s top job, never truly thinking, before the 2013 race, that they were going to be vying for it at the same time. It was one of the consequences of Mayor Thomas Menino staying in office so long that Walsh and Connolly started heading down the same road at the same time, Walsh believed.

For Walsh, Congress wasn’t an option, since Stephen Lynch, whose 2001 campaign both Connolly and Walsh had worked on, had settled into his seat. So had Menino, with five terms under his belt heading into 2013.

In 2005, an at-large Council seat opened up, due to Jamaica Plain’s Maura Hennigan attempting to block Menino from a fourth term. “If you ever run for office, I’ll be with you,” Walsh had told Connolly when they were both at the State House. Walsh made good on his pledge when Connolly jumped into the race for Hennigan’s at-large slot in 2005.

An old video surfaced on YouTube in the closing days of the 2013 mayoral race, showing the future rivals knocking doors together in 2005. They both wore the same outfits then that they would wear eight years later on the mayoral campaign trail: Walsh in a polo shirt, Connolly sporting a gold tie and rolled-up shirtsleeves. The only difference was that in 2005 both were wearing “Connolly for Council” stickers on their chests.

Catherine O’Neill, a local political activist and playwright who had her own cable access show at the time, had filmed the two of them on the at-large trail as a way to bring some attention to the down-ballot race. They were smiling, casual, and friendly, with none of the tension that would surface years later when they were pitted against one another citywide. “This is how you get elected,” Walsh said in the segment. “Retail politics. You go out, knock on doors, and you talk to people, explain who you are. This is how you win. The information superhighway doesn’t win elections.”

Connolly, a first-time candidate, finished third in the preliminary, but fell short in the final election, coming in fifth in the race for four at-large slots. But he won Walsh’s Savin Hill – Ward 13, Precinct 10 – with 428 votes.

A ‘risky’ play

After the preliminary, Walsh still had a name recognition deficit. “Right now, voters know little more than Marty is an Irish-Catholic union guy from Dorchester,” Bud Jackson, a Democratic media consultant, wrote in an email to donors. “That may have been enough to win the preliminary, but he now needs to bust out of that mold if he is to persuade other available voters in other Boston wards.”

Jackson, who hailed from Haverhill and worked on several local campaigns before decamping for Washington, D.C., led American Working Families, an outside labor-affiliated group with money to spend. Jackson’s group, like others that backed Walsh and Connolly, had legal leeway to raise the cash without limits and spend it without disclosing where it had come from in a timely way. After the election, the donors were revealed to be a variety of unions, from pipefitters to ironworkers and firefighters.

In an appeal to women voters, one populist-flavored ad from his group had teal colors and a warm font. Another positive and popular spot, called “Gunshot,” focused on a stray bullet that hit Walsh when he was 22 years old, then pivoted to Walsh’s work on legislation on a gun offender registry. “It is more difficult to move voters with just positive messaging alone. Is it possible to win by staying positive?” Jackson wrote in another email to donors. “My conclusion is yes it is possible. But it is also more risky.”

Jackson’s group started laying the groundwork early for a Walsh preliminary win, specifically focusing on the minority voters who were expected to be crucial in winning the final election, according to emails blasted out to donors and obtained by the Reporter. An Aug. 8 memo raised the possibility that African American, Hispanic, and other non-white voters would have to find a new candidate after the preliminary, since it was looking likely that two white Irish guys would be the finalists.

The American Working Families ad campaign, dubbed “We are Boston,” hoped to make a down payment in targeting minority voters and featured people of color. “We believe this will give Walsh a head-start at attracting these voters into his column for the November election,” the memo said.

A month later, Jackson provided an update to donors and prospective donors: He was working to cobble together enough money to target Latino voters, since it seemed unlikely that the Walsh camp, based on publicly available campaign finance filings, would have enough money to focus on those voters. It would be up to American Working Families to step in.

The negative ads the outside group put together took aim at links between the education reform groups backing Connolly and Big Business, like JP Morgan and Bain Capital. One ad opened with a snippet from one of Connolly’s television ads, which had him saying he will be the “education mayor.” The screen showed an empty teacher’s chair in a darkened classroom. His education plan is “backed by corporate interests and billionaires,” the ad continued. But the negative television ads, and those of other groups, would never end up airing, since neither side wanted to pull the trigger. They kept waiting for the other to go first. And Walsh had publicly stressed that he wanted to keep the campaign positive. When Working America PAC, another pro-Walsh group aligned with labor, distributed a flier attacking Connolly’s background, labeling him a “son of privilege,” running against a “son of immigrants,” Walsh angrily condemned it.

On the pro-Connolly side, Democrats for Education Reform, which had held its fire after the councillor said he did not want outside money in the race, was closely watching the pro-Walsh advertisements go up on the airwaves. On Oct. 11, the group’s Massachusetts branch said it had decided to disregard Connolly’s public request. Led by Liam Kerr, an alumnus of political campaigns in Massachusetts and Vermont, the group noted that both Walsh and Connolly “care deeply about improving our public schools” but they endorsed Connolly. “With just 25 days until the election and over one million dollars already spent by other groups, we feel compelled to directly tell voters the value of John Connolly’s experience as chair of the City Council’s education committee, as a middle school teacher, and as the father of a student in a turnaround school,” said the group, which released an ad featuring a Black social worker praising Connolly.

As campaign ads filled the airwaves, a bigger get was in the offing for Walsh: He pulled in crucial endorsements from former mayoral rivals such as Charlotte Golar Richie, John Barros, and Felix Arroyo, all candidates of color who didn’t make it past the preliminary. Just before a rally in Dorchester got underway, they joined Walsh in painting a powerful picture as they started to walk up the street to the microphone. That picture, snapped by campaign photographers and news cameras, would soon be everywhere – in campaign literature, on four-by-eight signs, and blanketed across Boston’s communities of color. The three supporters also appeared in a campaign video for Walsh, titled “One Boston.” “Marty Walsh will stand up for every person here in the city of Boston and every neighborhood in the city of Boston. Marty understands the struggles of working people because he’s lived it,” Golar Richie said in the commercial.

The one endorsement from a former rival that could have trumped all of the others was the one neither Walsh nor Connolly would publicly get: that of Thomas Menino. The popular mayor was leaving City Hall with a 79 percent approval rating, per a Suffolk University poll of 600 likely voters conducted just before the preliminary election. If he had a preferred candidate, Menino did not directly say so publicly, though there were whispers he had started directing some of his people to Connolly.

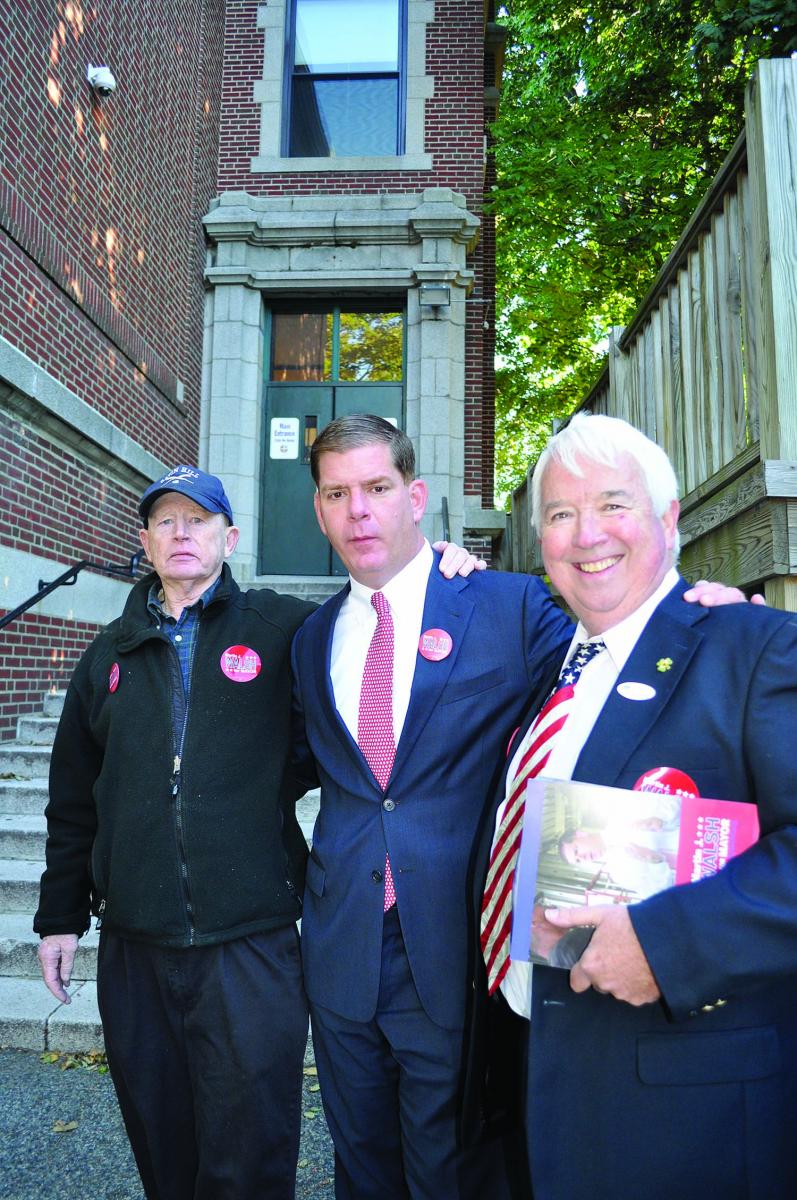

Rep. Walsh on Election Day 2013 outside of the Cristo Rey School in Savin Hill, a polling location for voters in Ward 13, precinct 10. Walsh is flanked by Danny Ryan, left, and Roger Croke, right. Walsh campaign photo

Election Day

On the final day of the campaign, Walsh broke off from the trail and his public schedule, and, joined by his girlfriend Lorrie Higgins, headed to Cedar Grove Cemetery, which spanned several acres along the Neponset River and featured a MBTA trolley line regularly rattling past the graves. His father John was buried there, near the front entrance, after succumbing to emphysema and skin cancer at age 82 in 2010. After they prayed together, the Dorchester lawmaker asked to have a minute alone with his father. As Lorrie started to walk back to the car, they both heard somebody call. “Vote for Marty Walsh!”

Walsh looked up and turned to Higgins, who swirled around. Was it a sign? “Oh my God,” she said. One more time, a tinny voice rang out from a campaign sound truck, making its way past the cemetery: “Vote for Marty Walsh!” Said Walsh, “It’s unbelievable.”

Connolly and his family, including his mother, his wife Meg, and others, spent much of the day spread throughout Hyde Park. After a quick stop at Holy Name Parish Hall, a super-polling location for four precincts, he headed to the Greenwood School, a high-voting location with a mix of Haitian, Caribbean, and white working-class voters. Connolly felt upbeat, but he noticed that campaign workers for two candidates gunning for the same District 5 City Council seat, Public Works Department aide Tim McCarthy and Haitian American activist Jean-Claude Sanon, were pushing Walsh. The sight made him uneasy.

Connolly had good reason to worry about Ward 18. The behemoth Hyde Park-Mattapan-Roslindale ward constituted the motherlode of election day swing votes. And the local contest between McCarthy and Sanon fueled the electorate in unexpected ways. Sanon was running a strong race and drove Haitian voters who were eager to add their first countryman to the council. Recently elected State Sen. Linda Dorcena Forry had thrown her support to Sanon, along with former state Rep. Marie St. Fleur. The pair were also allied with Walsh and were aggressively pushing both Sanon and Walsh on Haitian language radio and television programs. The Sanon-friendly precincts in the ward were expected to break Walsh’s way. But what of the McCarthy voters, who were dominant in Tom Menino’s side of the ward closer to Cleary Square and Readville? Was it possible that both Sanon and McCarthy voters would tilt into the Walsh column?

At 6 p.m., Walsh arrived at the Park Plaza Hotel and headed up to the penthouse suite on the 15th floor. He was still nervous. West Roxbury, Beacon Hill, and Back Bay had seen a high number of voters turn out. But he trusted his field team. “I heard it all day long on Election Day,” Walsh said. “People came up to me and said their doors were knocked on three or four times throughout the campaign.” Campaign workers were stationed at all four of the MBTA’s Red Line stops in Dorchester, pulling voters. “There were Walsh bodies everywhere,” the candidate recalled.

Inside the hotel room, he was joined by his mother Mary; his brother John; his cousin, Martin F. Walsh; Higgins and her daughter Lauren; his campaign manager, Meg Costello; and Tom Keady, one of his closest advisers and a top government relations official at Boston College. Walsh didn’t write down a concession speech, not out of arrogance, but believing that if he had to deliver one, he would speak from the heart. “At 7:30, I just got a feeling, a feeling came over me, that we were going to be okay,” Walsh said after the election. “And the nervousness went away.”

Fifteen minutes after the polls closed at 8 p.m., the numbers started to stream in. Sitting in one of the penthouse suite’s chairs, Walsh received text messages from friends and campaign workers who were feeding him results from precincts around the city. Alessandra Petruccelli, state Sen. Anthony Petruccelli’s wife, was the first to message him, telling him that he had won her East Boston precinct. She texted him again soon afterwards: He had won East Boston. The official tally later showed it was a squeaker: Walsh had eked out a win by 66 votes.

The numbers slowly reached the rest of the world as they were processed by the city’s Elections Department and shown on television. As the minutes ticked by, all but 13 precincts had come in. The Walsh campaign was up by about 2,100 votes. One of the precincts left was Ward 13 Precinct 10, where Walsh lived. He knew he had a 700-to-800 vote cushion there, and he repeatedly turned to Costello and asked, “Is Savin Hill in yet?”

Inside the offices of a local accounting firm, Team Connolly had set up the boiler room and it was busily crunching the numbers. Around 8:30 p.m., campaign manager Nathaniel Stinnett called him from the boiler room while Connolly was in the car on the way to the Westin Copley Hotel. “Look, we’ve got a little over half the city in and it doesn’t look good,” Stinnett said. All the numbers weren’t in yet, but they were not getting over 65 percent in West Roxbury, they were losing badly in Hyde Park, and they were waiting on the figures from downtown and Dorchester. Connolly got out of the car, and on his way into the hotel, he ran into several supporters. As his stomach churned, he struggled to smile.

Around 9 p.m., Stinnett called Connolly again. Eighty percent of the vote was in, and Connolly was down by roughly 4,000 votes. Looking out the hotel room window, Connolly saw the city stretched out before him, West Roxbury in the distance. He dialed Menino. “It doesn’t look like I’m going to make it,” Connolly told him. “I don’t have final numbers in yet, I’m waiting on downtown,” Menino said, urging Connolly to check in with him again later. The candidate called him back in five minutes: Things still looked bleak. He thanked Menino for being a “great mayor,” then stepped inside a windowless and smaller room off of the bathroom to make the call to Walsh.

For Team Connolly, the conversations in the closing days of the race always came back to Ward 18. They didn’t have a good sense of which way it was going to swing; their polling was all over the map. Walsh, whose campaign had sent door-knockers to Hyde Park the weekend after the preliminary, ended up winning every precinct in Ward 18, according to official results issued after the election, winning Menino’s home precinct in Hyde Park nearly two-to-one, 670 votes to 388 votes. The official final tally: 72,583 votes for Walsh and 67,694 for Connolly. Walsh’s winning margin was 4,889 votes.

Just before 9 p.m., Joe Rull, one of Walsh’s top field organizers, looked at his laptop inside the Walsh boiler room and realized they had won. As the realization spread around the table, the campaign’s staffers and volunteers looked at one another, attempting to comprehend what they had accomplished. Rull then stood up, his face turning bright red as he raised his fists into the air. “We won!” he shouted.

Matthew O’Neill Jr., a member of Walsh’s inner circle, called Walsh with the news. Walsh put O’Neill on speaker mode, so his words could be heard by the entire room: Marty Walsh was going to be the forty-eighth mayor of Boston. Mary Walsh and Lorrie Higgins started to cry and Marty’s brother John hugged him. The mayor-elect himself sat in shock and disbelief.

Connolly called soon after. “Congratulations,” Connolly said, as Walsh became emotional. “I should be the one crying,” Connolly joked. “You’re my mayor, I’m going to support you, and I know you’re going to do a good job,” he added.

Downstairs, in the Park Plaza’s Imperial Ballroom, Walsh consultant Michael Goldman, a veteran of Massachusetts political wars, was dealing with reporters who were hungry for the results. Goldman called up to the 15th floor and heard Keady tell him that they were on track to win. Armed with the information, Goldman walked over to Alison King, a New England Cable News reporter, and passed the word along: They were going to be victorious.

“What if you’re wrong?” King asked. “Hell, I’m old,” Goldman said, “who’s going to remember what I said?”

As Goldman made his way through the ballroom and up to the separate party for campaign staffers, he ran into a familiar face: Jackson, the head of American Working Families. With the polls closed and the election over, Jackson was allowed to be in the same room without running afoul of campaign laws. He and Goldman had once worked together in the 1990s, when Jackson was fresh out of college, but they had rarely talked since Jackson left for Washington. Goldman, like others, had noticed Jackson appearing at the end of the American Working Families commercials, as he was required to do in “I approve this message” fashion. “Jesus, your face is on TV more than anyone’s,” Goldman said.

Connolly gave his concession speech inside a small meeting room jammed with supporters and reporters at the Westin, three blocks away from Walsh’s celebration. “I respect the voters’ choice,” he said.

Back at the Park Plaza, Walsh was running late in delivering his victory speech. President Obama called to convey his congratulations. Vice President Joe Biden made several attempts to reach his future labor secretary, impeded by the fact that Walsh was not the only “Marty Walsh” in Boston politics. (The others included Walsh’s cousin and an unrelated political consultant.)

Walsh also took a call that night from the man he would be succeeding in January. “I’d like to have breakfast with you tomorrow,” Menino said. “Where would you like to meet, Mr. Mayor?” the mayor-elect asked. “Your new office,” Menino said.

Mayor-elect Walsh watched as confetti dropped from the ceiling at his victory celebration in the Park Plaza Hotel in Boston on Nov. 3, 2013.

Chris Lovett photo

Gintautas Dumcius is the digital editor of Boston Business Journal. He served as news editor of the Dorchester Reporter from 2010 to 2014. His ebook “This Way to City Hall” is the definitive account of the 2013 mayoral election in Boston. For a copy, send an email to gin.dumcius@gmail.com.