December 17, 2020

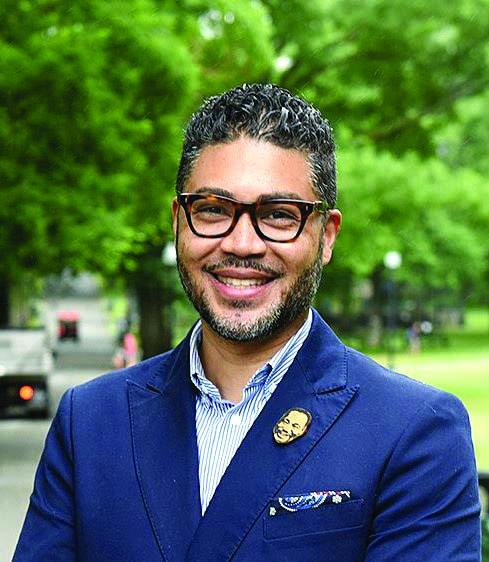

Imari Paris Jeffries

In 1966, a year after Martin Luther King Jr. came to Boston for the historic Freedom Rally march for fair housing, education reform, poverty reduction, and race equity, he went to Chicago to help local leaders fight discriminatory housing practices, one of the many ways that racism manifested itself in northern cities like Boston.

The Chicago campaign set the stage for national housing discrimination reform. As the country lay in mourning and crisis after Dr. King’s assassination on April 4, 1968, Congress moved to pass the Fair Housing Act, a law designed to safeguard people from racism and discrimination when looking to rent, buy, or finance a home.

But no single law could undo what decades of inequity and predatory practices had done to low-income people and people of color. Today, researchers from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition rank Boston as the third most gentrified city in the country. Our current fight against rampant gentrification and for affordable housing can be traced to widespread discriminatory housing policies in the mid-20th century.

Predominantly Black neighborhoods like Roxbury were redlined, denying residents the full benefits of homeownership. Predatory lending practices, artificially high-interest rates, and sales schemes resulted in home repossession, community instability, and created a subset of people who were confined to rental vulnerability.

Over the decades, Boston has topped lists of the most expensive cities to live in as we have seen dramatic increases in home prices and rents. Even during the pandemic, we see a surge in those prices despite dramatically declining inventory numbers. With those increases, diversity pays the cost. According to a recent Boston Magazine story, two-thirds of Black Bostonians live in one of three neighborhoods: Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan. And the most recent census data tell us that of the 147 Greater Boston municipalities, almost half —61— are at least 90 percent white.

For some reason, Boston has gotten away with being segregated. The last time the city had an opportunity to create a new neighborhood from scratch was the Seaport. And by any measure, diversity was not a consideration. For the companies, homeowners, to pre-COVID watering holes, the same patterns of segregations hold. The Seaport could have been different, a better reflection of the city we want to become.

In Dorchester, however, we are getting a second chance. The Dorchester Bay City project on the site of the former Bayside Expo Center is slated to be a $6-million-square-foot hub of housing, retail, and office space on Columbia Point. It promises new public spaces, access to the Harborwalk, retail, and a mix of live, work, and play.

As we are moving toward post-COVID and post-racial unrest and into a community of equity that Boston really wants to be, the Bay City could be the beginning. Here are a few ideas that could help:

Invest and offer incentives for Black, indigenous people of color (BIPOC) to establish and develop in the new neighborhood;

Increase the amount of affordable housing from 20 to at least 25 percent;

Ensure that there are workforce development and career opportunities so that residents also can have live/work experiences;

Subsidize non-profits to have offices and programming space in the community;

Have potential companies commit to the principles in the Black Mass Coalition’s re-imagining Boston document.

In his work, Dr. King laid out his vision of “the Beloved Community.” He described affordable homeownership as a crucial component to family stability and a proven means for providing families and communities with long-term benefits, like increased educational attainment, improved health outcomes, equity building, and civic engagement.

The promise of Dr. King’s Beloved Community requires Boston to acknowledge the full extent of housing insecurity and inequity in our city and establish housing as a right - and part of a new social contract. Put simply, the city must work together with local advocates and housing organizations to build and secure housing for all Boston residents.

And it can all start in Dorchester.

Imari Paris Jeffries is the executive director of King Boston, a nonprofit dedicated to honoring the legacy of Coretta Scott King and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. while addressing economic and racial inequities.