September 9, 2020

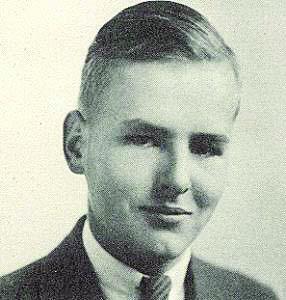

Joseph Beard

Dot soldier marched on Bataan in 1942, then died; remains were deemed lost--until now, it seems

The fog of war has hung over the family of US Army Staff Sgt. Joseph W. Beard for more than 75 years now, but maybe, just maybe, it is lifting a bit with the US Defense Department making inquiries about relatives of the soldier who died in the Philippines on June 14, 1942, after being taken off the Bataan Death March by the Japanese and assigned to cleanup duty back in Manila.

Joseph W. Beard was born on Aug. 25, 1921, one of the seven children of Joseph E. Beard and Mary Ann Hepp-Beard, who lived at 14 Linden Street, Dorchester, between Adams Street and Dorchester Avenue. He grew up in St. Peter’s Parish and later moved to Port Clinton, Ohio, where he lived with his grandparents and worked as a hotel bookkeeper. In 1938, at age 17, he joined the Ohio National Guard and was assigned to his hometown tank company, beginning a short life of service to state and country that took him over the next four years to Fort Knox in Kentucky, to Camp Polk, Louisiana, and, in the summer and fall of 1941, to Ft. McDowell on Angel Island in San Francisco, to Honolulu, to Guam, and, finally, for him, to the Philippines.

His ship entered Manila Bay, at 8 a.m. on Thurs., Nov. 20, 1941, and docked at Pier 7 later that morning where his company was greeted by an armed military party whose commander told the soldiers to “draw your firearms immediately; we’re under alert. We expect a war with Japan at any moment. Your destination is Fort Stotsenburg, Clark Field.”

The information above and what follows have been taken for the most part from US government files compiled after the war.

Dec. 7/8, 1941: Bombs Away

On Dec. 7, just before 8 a.m. Hawaii time, Japanese planes dropped out of the clouds over the island of Oahu and wreaked devastation on the people, ships, and property at the US Naval Base at Pearl Harbor. Ten hours later, but across the international dateline, making it Dec. 8, Sgt. Beard and Co. were in the field when bombs began exploding around them, dropped from Japanese planes that seemingly never stopped coming. For this St. Peter’s boy, the war was on and he was in it, along with his comrades and many millions of others, looking at a future with lots of unknowns attached. And for those facing the invading Japanese forces in the Philippines, the following four months were rife with the chaos of battle as American and Filipino forces fought the Japanese wherever they encountered them. But the dogged defenders were outmanned and eventually found themselves backed into dire straits in the province of Bataan on the island of Luzon.

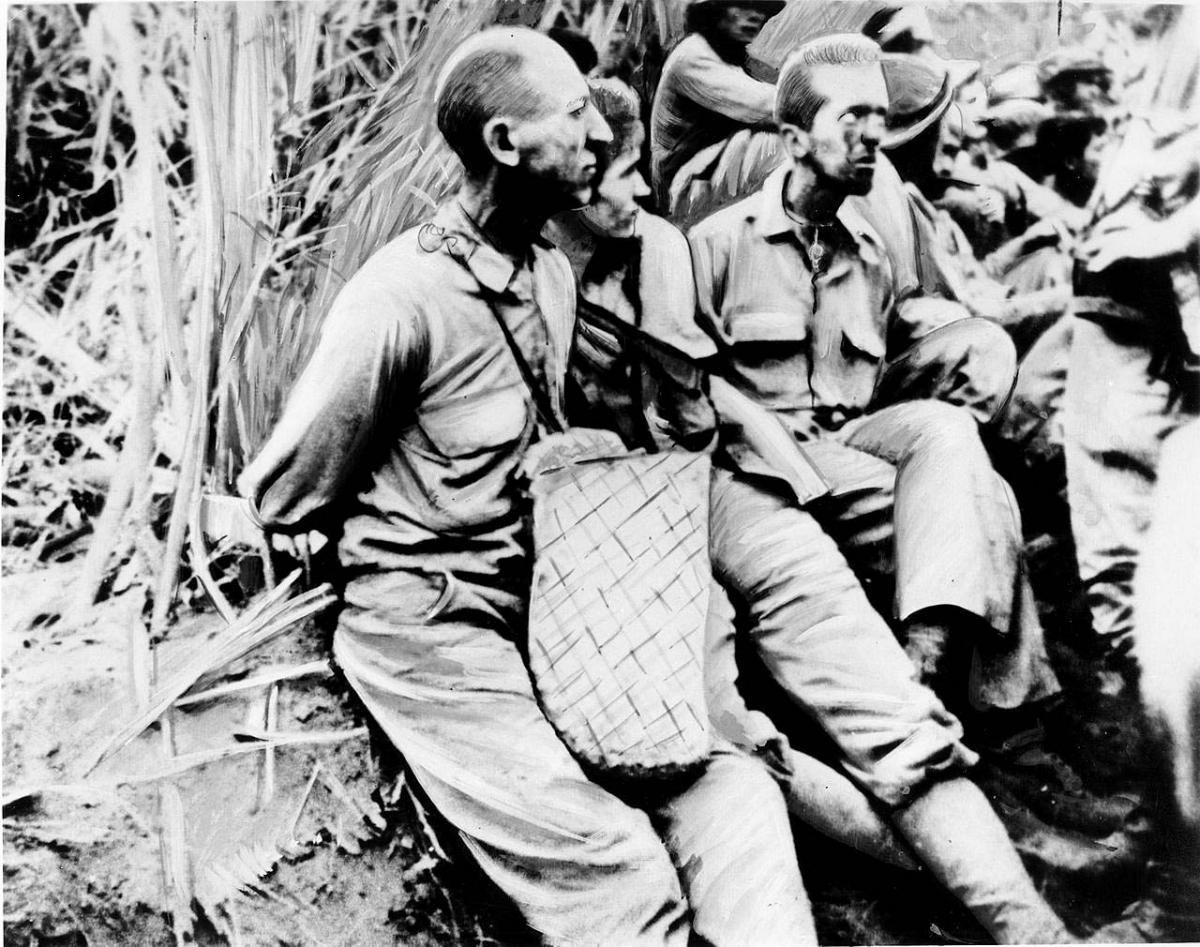

On April 8, 1942, the commander on scene, Gen. Edward P. King, decided that further resistance was futile and gave up the fight, and his combined forces. On April 9, Joseph Beard was among some 75,000 American and Filipino soldiers who were now prisoners of war. Their captors then organized a march of some 65 miles to the trains that would take the POWs to prison camps. Participants reported later that they were brutally abused by Japanese guards, given little food and almost no water. As Sgt. Beard and his company made their way north, they walked past artesian wells with water flowing from them. Anyone attempting to get a drink was shot or bayoneted.

Certifiable figures concerning the Japanese march of American and Filipino POWS on Bataan in April 1942 are hard to come by, as is extensive photographic evidence. Consensus estimates are that of the 75,000 or so POWS forced to traverse the 65-mile route, about 54,000 survived. This Associated Press photo by way of the US Marine Corps was reportedly stolen from the Japanese during their three years of occupation of the Philippines during World War II.

According to records kept by officers of his battalion, Sgt. Beard was reported missing during the march. He apparently had been selected out of the line by the Japanese for a work detail back at Fort Stotsenburg where he and other prisoners cleaned up the grounds of the base and lived in their former barracks.

While on the detail, Sgt. Beard reportedly became ill with dysentery and died on June 14, 1942. He was said to have been buried in a grave with four other POWs in the cemetery at Ft. Stotsenburg. For some reason, the Japanese apparently never reported his death to the Red Cross, so his family did not learn of his passing until after the war, in late 1945.

His father passed away early that December, and a funeral Mass was said for him at St. Peter’s Church. The liturgy also served as a memorial Mass for his son, the sergeant.

Early the next year, in February, a report that suggested finality, at least for the Army, as to what happened to S/Sgt. Beard noted that his remains and those of the men buried in a grave at Fort Stotsenburg had been exhumed and reburied at the American Military Cemetery at Manila.

A mother seeks information

But the story doesn’t end there, at least not yet. For one thing, Mrs. Mary Ann Beard, the sergeant’s mother, wasn’t satisfied with the crisp assertion of her boy’s death by the Army, and as late as 1950 was writing letters in longhand inquiring of various Army offices: “What did my son die of? Where? Where is he buried? Also, if he had a priest? If you can’t give me what I ask for, please say so.”

That last plea evoked a letter from a Capt. J. F. Vool on May 19, 1950, which said, in part:

“It is with deep regret that your government finds it necessary to inform you that further search and investigation have failed to reveal the whereabouts of your son’s remains. Since all effort to recover and identify his remains have failed, it has been necessary to declare that his remains are not recoverable.

“Realizing the extent of your great loss, it is with reluctance that you are sent the information that there is no grave at which to pay homage. May the knowledge of your son’s honorable service to his country be a source of sustaining comfort to you.”

This was the last word that his family received from the government. Since his remains have never been identified, S/Sgt. Joseph W. Beard’s name appears on the Tablets of the Missing at the American Military Cemetery at Manila, according to bataanproject.com, a website that continues to chronicle the lives and times of those forced to make the death march in April 1942.

An inquiry from Washington

Last month, Jim Opolony, the curator of bataanproject.com, was contacted by a researcher for the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA), the Department of Defense branch charged with recovering the remains of some 80,000 missing members of the US armed forces.

Wrote Opolony in a letter to Earl Taylor of the Dorchester Historical Society, who sent it along to the Reporter: “It appears that Sgt. Beard’s case is considered active by the Department of Defense and they are doing research on him. This means they will be attempting to find family members for DNA. If you go to bataanproject.com and search for Joseph W. Beard, his page will come up. Open the page and you can read about him.

“All I am doing is attempting to make his relatives aware that DNA is wanted so his remains will be identified and possibly returned home. In particular, children or grandchildren of his sisters will be wanted for DNA because of the archaic DNA testing done by DPAA. The family can initiate the DNA testing, but does have to wait for the DPAA to contact them.”

The next step? Hard to tell

That last admonition by Mr. Opolony is well taken, at least by the Reporter. I was given two names at DPAA to contact if I wanted to get some supporting information for this story. Late last month I wrote a letter to that department’s Gregory J. Kupsky and I called the section’s public affairs office (703-699-1420). A Sgt. Sean Everette answered with a message noting that he was working from home during the pandemic and could be reached at his email address. So I sent him a letter by email.

In my correspondence, I asked them if they could in any way amplify details from this report for Reporter readers who might know how to contact later generations of members of the Beard family that lived in Dorchester. Mass., before, during, and after World War II.

To date (Sept. 10), no replies.