June 4, 2020

Two boys in uniform led a contingent of marchers representing the Vietnamese-American Community of Massachusetts in the Dorchester Day Parade last year.

Editor's note: Dorchester Day is traditionally observed on the first Sunday in June. However, the 2020 Dorchester Day Parade was cancelled due to the COVID-19 health emergency. In the spirit of safely celebrating Dorchester Day this weekend, this week's Reporter includes a package of Dot Day-related stories, including this one from our longtime friend and contributor Chris Lovett.- Bill Forry, Editor

An annual march that displays recurrence, resemblance, and change

The first time I saw a Dorchester Day Parade, I figured I was too old to be impressed. It was June 1977. I was a 24-year-old Dorchester native, barely emerged from college and the shallows of the counterculture. As a reporter on a weekly neighborhood paper, I showed up with a notebook and camera, expecting little more than a generic display trying to pass for spectacle. Not trying to relive the excitement of childhood, I would set my sights on the plain, particular, and momentary.

I didn’t know at the time this encounter with the parade would be repeated about 20 times over a period of more than 40 years. During that time, the parade, its route along Dorchester Avenue, and the whole city would change in ways I didn’t expect. What starts as plain, particular, and momentary—going from here to there—becomes something less linear: a composite pageant of recurrence, resemblance, and change.

Change also applies to observers. After so many revisits, an internal compass draws a map filled with landmarks and topographies, sites of places that or may not still exist. It’s a little like what happens in the John Cheever story, “The Swimmer,” where the idea of plunging through a succession of backyard pools generates the feeling of being “a pilgrim, an explorer, a man with a destiny.”

Like many in Boston, I had my earliest up-close encounters with a parade on St. Patrick’s Day, and the one I remember most clearly was when I was about 10 years old. My father was a Boston firefighter, so he arranged for me to watch the parade from the quarters of Engine 1 on Dorchester Street. Leaning out a window on the second floor, I had a drone’s eye view, with a swarm of spectators down below, parted by a stream of marching units making a turn at East 4th Street.

What parades do: Relax boundaries

What I took in were colors, formations, and music that were different from the everyday neighborhood, as were the groups of people dressed as soldiers, sailors, saints, and clowns. If there were first responders going by, there was no frantic race to an emergency—just sheer display, exultant with sirens. Those of us using a firehouse as a gallery were just one more exception from normal. That’s what parades do: relax boundaries, even between everyday reality and passing spectacle.

Fast forward to Dorchester Day in the late 1970s, and there I am, looking down from the second floor of another firehouse, Engine 18, in Peabody Square. When I check the view from the loggia in a black and white photo, I note the crowd. There’s little sign of racial diversity, but I’m really struck by how dense the crowd is, blurring boundaries between sidewalk and avenue, not to mention the difference between spectators, the marching band from St. Peter’s CYO, and the occasional kid on a bike.

Sometimes the difference between parade and spectators involves little distinction. If it were the band from St. Peter’s, St. Ann’s, or St. William’s, the marchers would be mostly young people from the surrounding neighborhoods—or parishes. The same went for other contingents in uniform from the Cedar Grove or Mill Stream little leagues. But these local units also had something in common with others going by in uniforms, whether active soldiers and sailors, veterans, or police.

You could say there was a difference was between those in outfits and those who came as they were. Sometimes the difference was more noticeable in behavior, with an orderly procession greeted by something more spontaneous. The greetings were mostly friendly, but sometimes there were insults or reminders of Boston’s acrimonious racial climate more than 40 years ago. There was even be a bottle lobbed at a tank that caused an injury, and the lone spectator on a sparsely populated stretch of the avenue near Glover’s Corner who accosted a governor with a handshake and some choice words unfit to print.

Urban streetscape icon: The doughty three-decker

Much more often, those who came as they were simply took in the show. If not standing along the avenue, they gathered on three-decker porches, perched in rows on a billboard, or on the roof of the Englewood Diner near Peabody Square. If some part of the parade seemed not so picturesque, I could just turn around and focus on faces looking down from windows. Or on the makeshift decorations that could just as easily been attached to a float.

What you see looking back from the parade is a landscape, part of a built environment dominated—more than anything else—by wooden houses, especially three-deckers. From one year to another, I would see a three-decker on the Dorchester tee-shirt sported by the longtime activist and community advocate Lew Finfer. If nothing else, he understood that the same building, like the avenue itself, could channel the passage of different people through the years.

“Imagine,” he wrote, “if you just could do a history of just one of these thousands of buildings in Dorchester and the many people who lived in even one of them over the last 100 years and what their lives were like with the blessings and tragedies.”

At Dorchester Park, the landscape had spectators on the grass under a canopy of trees, several in spots staked out with folding chairs. Farther downstream, the crowd would thicken again, at Peabody Square, St. Mark’s Church, Fields Corner, Savin Hill Avenue, and Edison Green. There was a progression of sorts, from the look of a small town to increasingly commercial density and visual clutter. Beyond the finish line at Columbia Road, in a gathering summer haze, there would be a far-off glimpse of something unlike the angular, wood-frame texture of Dorchester: the hard, rectilinear planes of downtown office buildings.

Taverns, funeral homes, and praying the Rosary

As one neighborhood leader wisecracked about 40 years ago, the avenue’s commercial design standards were dominated by bars and funeral homes. I didn’t go inside the bars all that often, but they were a kind of positioning system, marking your whereabouts with names like Tara Pub, Town Field Tavern, Irish Rover, Mallow’s, Peter & Dick’s, Tom English, and Vaughan’s. Little wonder that a number of the bars would be showcased one year by a parade float, complete with kids and adults at tables. I came across them before the start of the parade, just as they were looking across the street at the altar boys and First Communion girls arranged on another float with a sign that said, “Pray the Rosary.”

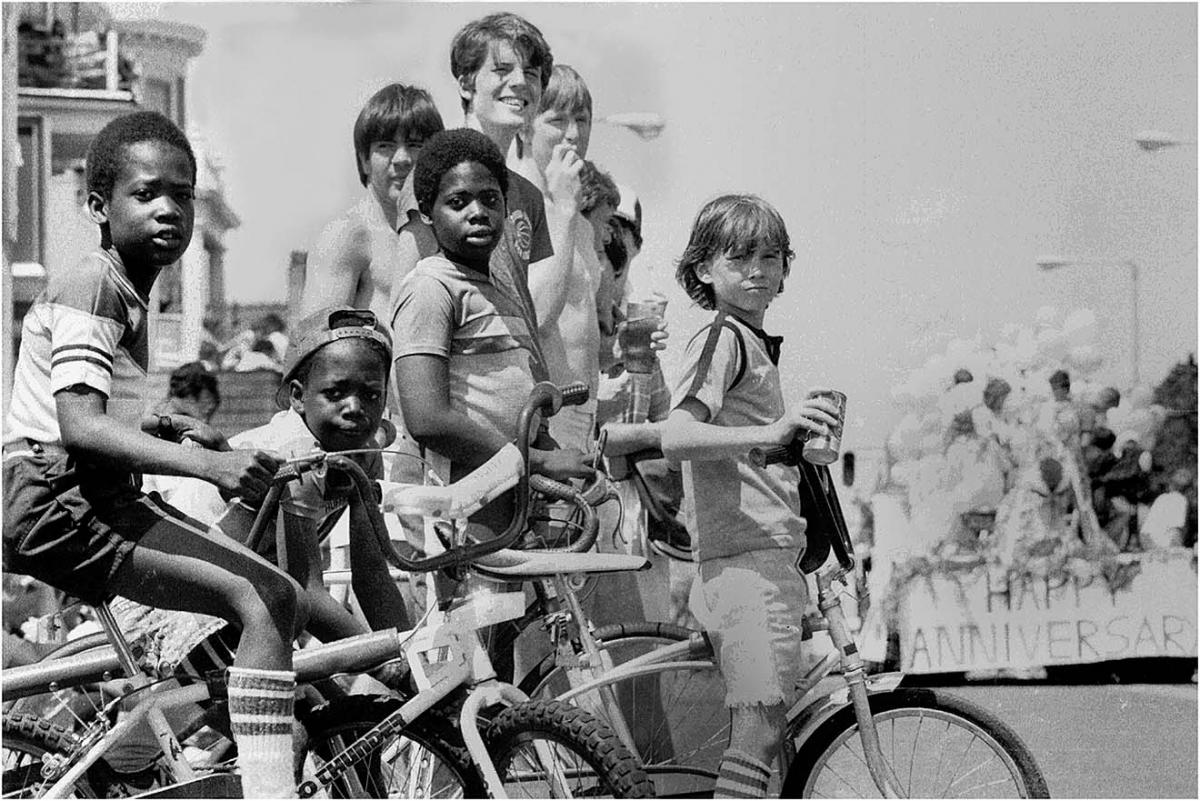

By the early 1980s, the cross-section of people at the parade noticeably reflected changes in Dorchester’s population. That could mean the diverse group of soccer players from the All Dorchester Sports League, which was organized in the 1980s to help surmount racial divisions. But there were other times when racial diversity could also be a random mix of people enjoying the view from Dorchester Park, or boys—possibly from different streets, who pulled up with their bikes to watch from the same place on the avenue.

Just as the influx of Vietnamese immigrants would be reflected in the avenue’s stores and restaurants, they would also make their contribution to the parade. There were South Vietnamese military veterans in uniform, beauty queens, kids dressed for martial arts displays, and rotating crews of lion dancers. As they slithered from one side of the avenue to another, the lions would always find people—usually kids—reaching out their hands. Each time, a boundary would be crossed, from the practiced performers on the street and more spontaneous performers along the sidewalk.

The fluid boundaries would be more noticeable as the parade was joined by Caribbean-American contingents dressed for carnival. By “playing mas,” everyday people could take on the role of royals or something more colorful and fantastical, even blurring the distinction between fauna and flora.

‘As diverse as the crowd that surrounds us’

The floats by DotOut were a warm-up for Boston’s Pride Parade, conspicuous but far from the exception in their celebration of artifice and exaggeration. The topics changed from year to year, from beachgoers to abominable snow creatures. On the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, the DotOut float was a collage of causes. The message was about things in common between different people, but also about straddling the boundary between earnest protest and the spirit of play.

For DotOut president Chris McCoy, there’s a connection between his experience as a ten-year-old seeing the Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade in New York City and what he describes as the “palpable feeling of excitement and emotion” decades later on Dorchester Avenue. “For us,” said McCoy, “we have been providing a unique perspective around the LGBTQ community in Dorchester and how we are real people, as diverse as the crowd that surrounds us.”

Over the years, diversity would also mean a succession of dancers, like different numbers from the same musical or ballet: Irish dancers, then choreographic columns of Estrellas Tropicales, Fuerza Internacional, Roberto Clemente 21 Dancers, and 4 Stars Dance Studio. I note the formations, the changing colors of costumes, and likewise for outfits worn by the Thomas Kenny Elementary School Marching Band. With a camera, I also search for signs of excitement, fatigue, concentration, or someone recognizing a friendly face. And, not the least, there’s that Irish dancer who, caught in one fraction of a second, will forever be in mid-flight above her shadow on the pavement of Dorchester Avenue.

For the Smedley D. Butler Brigade of Veterans for Peace, the most consistent marker is the yellow banner. In the 1980s, the groups of Vietnam-era veterans looked less like former soldiers than young protesters. Decades later, the banner and the message are the same, but the brigade has become a fixture, while its aging members show the parade is also a journey through time.

Just walking the length of a single parade can exert fatigue and dehydration, especially for the most active participants. Burdened with only a camera, I could just walk, even savor the rare opportunity to go on foot where it’s usually off-limits to pedestrians. Without its usual traffic, and the normal sense of going from here to there, the avenue becomes more of a here and now.

Dorchester Town Greeter “Boston Billy” Melchin was a familiar presence at the parade for a generation. He is shown here traversing Dot Ave in 1980. Chris Lovett photos

The welcoming white-gloved hand

If there’s an overextended gap between parade units, the sense of formation dissolves and people start roaming in the avenue, as if driven by an urge to fill a vacuum. At a loss for something to shoot, I meander or look in different directions. And that’s when the young people on wheels take over.

Usually restricted to cruising Dorchester’s side streets, the kids see this unclaimed interval as an opening. In one year, there’s the impromptu squadron biking in a formation of its own through Fields Corner. In a black and white photo from more than 30 years earlier, there’s one kid on a bike and another on a skateboard—separately threading a maze of wayward spectators. In the middle of it all stands the Dorchester Town Greeter, “Boston” Billy Melchin. With a raised hand in a white glove, he stands with a look of gentle authority, for all I know, maybe telling anyone who might care to notice that they’re welcome to avenue.

Tags: