February 26, 2020

A section of the Neponset River between Hyde Park and Lower Mills could be up for "superfund" designation by the EPA.

‘Superfund’ status, clean-up could be in play years later

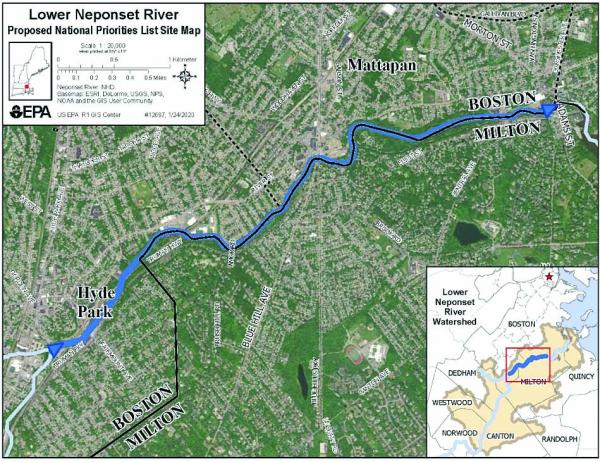

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) will seek a “national priority” designation for a 3.7-mile section of the Neponset River that flows from Hyde Park to Lower Mills, according to agency officials who briefed a group of about 70 people at a public meeting on Monday night at Mattapan’s Mildred Avenue Community Center.

This is a step that may eventually make the river eligible for federal “Superfund” status leading to the clean-up of the designated section, which remains contaminated from industrial pollution that has been deposited into the river over more than two centuries.

Sediment in the Lower Neponset contains elevated levels of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), which are hazardous to human health, fish life, and the environment. The PCBs are a grim reminder of the Neponset’s polluted past, when factories along its shore used the river as a place along its shores would dump their chemical waste into the water.

“At this point we want to talk about the fact that we think we’re going to move forward with this action, and we want to continue communicating with folks about the process,” said Meghan Cassidy, the EPA’s supervisory environmental engineer in New England.

The state’s Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) asked the federal agency to consider adding the Lower Neponset to the EPA’s National Priority List (NPL) two years ago, according to Steve Johnson, the state agency’s Northeast Regional deputy director.

“From my experience working with the EPA, this process seems like the best move for a site like this, one that might otherwise not get cleaned up,” said Johnson. “The EPA has taken on some of the more complicated and costly site cleanups in the state.”

He added: “In this case, MassDEP was asked to help identify sources of PCBs that were behind the dams in the Neponset River going back ten or twelve years. We took a survey that identified some really high concentrations of PCBs at Mother Brook and saw that this was going to be a very complicated and expensive liability case.”

The EPA evaluates sites by conducting preliminary assessments, Cassidy said, that determine if they “rise to the caliber” worthy of a designation to the NPL, which then establishes a site’s eligibility to receive Superfund program assistance.

She noted that the classification — and any federal funding that might come with it — is contingent on determining responsibility for the pollution, a legal process that involves researching past practices and assigning culpability. The EPA cannot delve into those investigations or complete a comprehensive site evaluation without first adding the site to the priority list.

“The work we have done to date is by no means an effort to fully evaluate the extent of contamination,” explained Cassidy. “The EPA cannot do that until after we place the site on the NPL. These studies are in no way, shape, or form meant to be comprehensive. The full evaluation comes later.”

Attendees expressed curiosity about what parties that might be responsible for pollution, besides the Lewis Chemical Corporation, which dumped hazardous material into the Neponset during the last century.

“We don’t have a full list of responsible parties, that investigation doesn’t happen until the site is added to the NPL,” explained Cassidy.

Sites are added to the NPL through federal rules, one of which requires a letter of concurrence from the governor. After a site is proposed to the NPL, a 60-day public comment period ensues before the proposal is finalized. When a site is added, the next step for the EPA in its long-term Superfund process is to begin the comprehensive probe of parties responsible for the pollution and then start initial clean-up efforts.

The EPA is already at work assessing where the Neponset River site fits in its Hazard Ranking System, which is documentation that they need to propose the site to the NPL. Other things being equal, the team thinks that the EPA could finalize the site to NPL sometime next year.

“We want to be open and clear that the Superfund process is a lengthy one. The investigation will take several years and the cleanup will take many more,” said Cassidy. “Right now, we’re at the very start…and we will be having many more meetings.”

Many of those who were at Monday’s meeting flagged concerns over the current signage along the river, saying that in some areas, signs don’t warn the public not to fish or swim in the water. A few also pointed out that the signage isn’t accessible in languages other than English.

Leon David, an aide to state Rep. Dan Cullinane, said that the signage issues are on Cullinane’s radar, adding that “there have been changes within DCR that have slowed the process down, but he is aware of concerns for appropriate signage along the river and we’re in the process of working on that.”

Ian Cooke, the executive director of the Neponset River Watershed Association (NepRWA), said he’s very excited to see the process getting started. His group has spearheaded efforts over several years to clean up and improve areas of the river. Those efforts prompted MassDEP to investigate the build-up of sediments around dams, which led to the discovery of hazardous PCBs.

Cooke asked the EPA team to explain exactly where and how people might come in contact with the contamination.

“The sediment is at the bottom of the river, and if you aren’t exposed to something, there’s no risk,” said Cassidy. “If you’re not swimming or walking through it, we don’t expect that there would be exposure.” She noted that PCBs bioaccumulate in fish, and communication of that issue to the public has been a longstanding concern.

Fatima Ali-Salaam, chair of the Greater Mattapan Neighborhood Council, asked the EPA officials to connect with local organizations by meeting local civic groups and neighborhood associations where they gather.

“In the effort of trying to be healthy and be active, people want to be engaged with projects like this because they want to use public spaces like the Neponset River,” she said. “It would be great if you came out to the neighborhoods, which are all connected; information will compile and travel.”

She also noted, “There are members of major groups here tonight,” pointing out people and listing neighborhood associations, “Within this room tonight, I think we could pull together 1,000 people in our networks. If you really want people to buy in you have to come out and engage them where they are,” a sentiment that moved the attendees to break out in applause.

Doug Gutro, EPA’s regional Director of Public Affairs, said the team would definitely engage with local groups going forward.

“We can be a resource and we will be a resource. We know that we’re in this for the long haul and this is your community and your backyards,” said Gutro.

Marcus Holmes, the EPA’s Environmental Justice coordinator, is working to create a team that will work more closely at a hyper-local level. “We’ve been doing a lot of work coordinating with our city and state partners,” he said, “but I want to let you all know that we’re also trying to do a better job of getting down on the local level. One of the things I’m trying to do is put an internal team together to do exactly that type of outreach.”