June 12, 2019

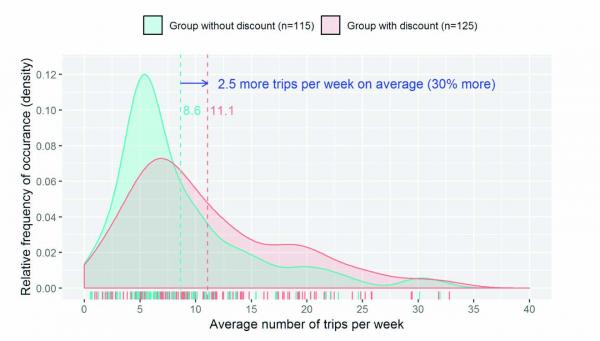

Low-income riders who received reduced-cost CharlieCards took 30 percent more trips per week on average than low-income riders without them, an MIT study has found.

Activists are urging MBTA officials to work toward a fare subsidy for low-income riders, saying rising transit costs are forcing too many riders to choose between traveling to jobs and medical appointments or buying food.

At an MBTA board meeting on Monday, Boston City Councilor Michelle Wu and others pointed to a MIT study showing that low-income riders who received a subsidy took more MBTA trips, including trips for health care and social services, than those who used a non-subsidized CharlieCard.

“The preliminary findings of the MIT study released this morning provide strong evidence for something that every T rider knows is true,” Wu said. “The cost of fares matters for those who need public transit the most and we need to make sure we’re doing everything we can to lower barriers that the fares impose.”

In a study of 240 low-income riders during random two-month periods between February and May 2019, MIT researchers placed participants in either a control group or a group receiving a deeply reduced transit pass.

Researchers tracked CharlieCard usage data to determine any differences in travel behavior, such as the average number of trips taken by each group and the time of day those trips were taken. They also collected daily travel diaries from each participant using the automated ChatBot, incentivized through a $5 daily lottery with multiple winners. Participants answered survey questions before and after the study, addressing topics like barriers to using public transportation.

A full analysis of the report is not yet available, researchers note, but top-level takeaways showed a dramatic alteration in transit habits for riders receiving a 50 percent discounted CharlieCard.

“In sum, we found that low-income riders in the study took 30 percent more trips as a result of receiving a subsidy and took more trips to access health care and social services,” the report’s authors wrote. “We also found that, compared with the average MBTA rider, the low-income individuals participating in the study took more of their trips during off-peak times, relied more heavily on buses and Silver Line, made more transfers among modes and routes (e.g., subway to bus to another bus), and more often paid with stored value on a card rather than one-day, seven-day, or monthly passes. They also reported reliability, affordability, frequency, and crowding as top concerns.”

The report notes that little is known about the impact of measures to address transit affordability measures, though regions like San Francisco and Seattle offer discounts to poor riders and federal policies mandate discounts for the elderly and physically disabled. The MIT study, funded in part through the MBTA advisory board, aimed to assess the usage patterns for food stamp recipients when given more affordable public transit access.

Paul Regan, executive director of the MBTA Advisory Board, said at the meeting that “the overall fare levels are a factor in the social safety net.”

MBTA fares, which are scheduled to increase on July 1, have risen 41 percent since 2012, said Wu, who also protested rising commuter rail fares that she said will soon require a person living in Readville, a section of Boston, to pay $232 for a monthly pass.

During debate about the fare increases in February, Wu submitted a petition with thousands of signatures opposing the proposal and even argued that MBTA service should be free to all riders.