February 14, 2019

Boston Public Schools will start administering the entrance exam for its three “exam schools” during the school day next fall. Some activists praised the change as a step in the right direction, but said it will take more than a scheduling change to foster diversity at those prestigious schools, especially Boston Latin.

The change — which will cost the district around $340,000 — was announced on Feb. 6 as part of BPS’ proposed budget for the 2020 fiscal year.

Interim Superintendent Laura Perille described the new policy as an “equity investment,” adding that it “will help to flatten barriers for students and increase demand and appetite for students to take the entrance exam and apply to exam schools.”

In the past, students who hoped to attend Boston Latin School, Boston Latin Academy, or the O’Bryant School for Science and Mathematics would take the Independent School Entrance Exam (ISEE) on the weekends — which, district officials said, may have impeded some students from even taking the chance.

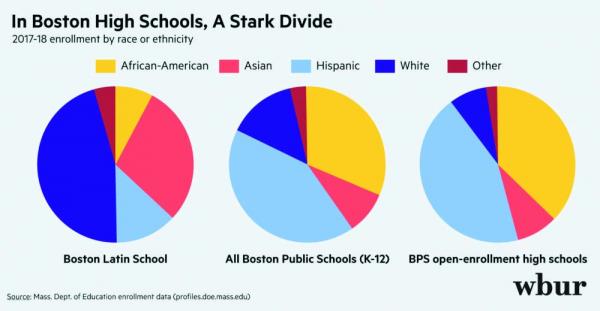

Procedural barriers like that may play a part in the alarming racial disparity separating the exam schools from their peer institutions that are open for all to enroll.

At Boston’s largest open-enrollment high schools, 87 percent of the students are black or Latino. At Boston Latin School, the number is 20 percent.

A report issued in 2017 by the NAACP and other organizations contended that none of the exam schools “reflect the diversity of our city,” and that students from private schools or majority-white neighborhoods had elevated odds of acceptance to the exam schools.

That report also found no shortage of exam school applications coming from minority students in the city, which may suggest that the test administration is not the only factor contributing to the disparity.

In 2016, Boston Mayor Marty Walsh committed to expand an annual test-prep program, free for all BPS students, calling it “an important step forward” for diversity.

This latest change will try to grow the pool of applicants to the schools. District officials project that administering the test during the school day will allow some 1,400 more students to take the test than did last year.

Monica Roberts, BPS’s chief engagement officer, said last week that those students will be chosen for their readiness based on past academic performance. “We will pre-select sixth graders, and identify and connect with those families,” she said. But she added that all “families who want to take the test [in school] will be allowed to do so” on an opt-in basis.

The organizations behind the 2017 report praised the new rule, though with some reservations about its hoped-for effects.

Among them was Iván Espinoza-Madrigal, director of Lawyers for Civil Rights, which has made exam school diversity one of its top policy priorities. “Administering the test is just one step. What are we doing to prepare students for this test?” Espinoza-Madrigal said. “None of our public schools teach a curriculum that prepares students for what is a private-school exam.”

Other advocates agreed that for many BPS students, the course work through sixth grade simply isn’t rigorous enough to prepare them for the ISEE. And they point to the numbers, with much higher ‘pass’ rates for students from majority-white neighborhoods and majority-white schools.

That’s proof enough for Rev. Willie Bodrick II, chair of the Boston Network for Black Student Achievement: “We’re looking at a situation where a lot of our young people, even if they did everything that was asked of them, aren’t prepared for that test.”

Bodrick added that an eternal question in education policy applies here, too. “How much should we depend upon [a] test to capture what a person’s trajectory might be — the person as a whole person?” Bodrick asked.

Neither Espinoza-Madrigal nor Bodrick proposed taking the exam out of exam school admissions altogether, though both raised questions about the use of the ISEE.

Espinoza-Madrigal, who is an attorney, proposed that Boston write its own test for its own particular environment and that it embrace something like Harvard’s “holistic” approach to admissions. Harvard’s approach is currently under scrutiny in federal court for its purported discriminatory effect on Asian-American applicants, but Espinoza-Madrigal stood by it.

“Because that case continues to be litigated, the formula used by Harvard continues to be legal — an option any school can consider,” he said. So balancing test scores and middle-school grades against personal characteristics, he added, is “good law, until the court says otherwise.”

Lawyers for Civil Rights will host a community forum on exam-school admissions at the end of this month, and Espinoza-Madrigal said they’ll continue to push the city for a more comprehensive change.