January 9, 2019

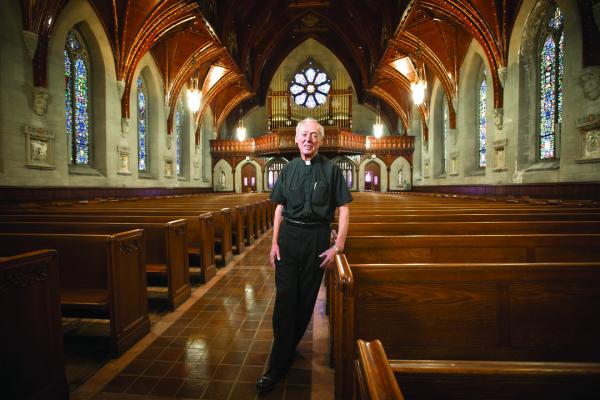

Rev. Richard “Doc” Conway at home in St. Peter’s Church in spring 2014. Tom Kates Photography

Late one recent afternoon, while the rest of us were worried about the big things in life, like Kate Middleton’s net worth, Melania’s safari helmet, and whether A-Rod feels constrained by JLo, an elderly Roman Catholic priest named Fr. Richard Conway, or “Doc,” as everyone knows him, was doing what he often does, walking the streets of immigrant Dorchester, speaking in English, Spanish, and Portuguese, and worrying about the small things in life, like whether Tony Barbosa would be deported, at age 30, to Cape Verde, a country he’s never seen, and whether Zamira, three, will sip booze from her great-grandfather’s plastic cup, and about the next tour Fr. Conway will lead for students of Boston College High School that will open their eyes to poverty, crime, and desperation in a part of Dorchester unknown on the hard-bitten streets of Hingham, Newton, and Wellesley.

The Boston Irish Reporter is honoring Fr. Conway for his remarkable ministry in Dorchester as an indefatigable advocate for marginalized youths, and yet, that does not fully describe the six decades in which he has contributed to Greater Boston, and especially now, at age 80, what he is giving to the youth of Dorchester, to the image of the Catholic Church, and to the heritage of Irish clergy.

In nine years, Fr. Conway is the first person to offer not to receive the Boston Irish Honors award. After recipients were notified, the Roman Catholic Church was rocked by news of a sex scandal in Pennsylvania, and in an act of grace, Fr. Conway telephoned the publisher of the Boston Irish Reporter, Ed Forry, to say that if the newspaper wanted to withdraw the award, he would understand.

His ministry in St. Peter Parish on Meetinghouse Hill, St. Ambrose in Fields Corner, and St. Teresa of Calcutta on Columbia Road, formerly St. Margaret’s, and especially his courageous walks through gritty neighborhoods to encourage troubled youth, rather like a Shepherd of the Streets, he is a reminder that when Jesus said to his disciples, “Follow Me,” what he may have had in mind was Fr. Conway, or as Christ would have called him, “Doc.”

•••

Richard Conway grew up in Roslindale, graduated from Boston College High School and St. John’s Seminary, and was ordained in 1963, but it was not until 1980, after he had served parishes in South Weymouth, Framingham, West Quincy, and Hyde Park, that he found his ministry to the poor at St. Patrick’s, Lowell, a parish suffocated by debt and challenged by rampant immigration, by an impoverished congregation that had dwindled from 5,500 to 2,000, and by financial credit so weak the parish could no longer borrow money. Even the milkman was owed $2,000.

Later, after serving in Newton, Concord, Shirley, Randolph, Brockton, and Somerville, Fr. Conway was assigned to Dorchester, and in its focus on the poor and upon immigrants, the Dorchester ministry is a bookend to his early work in Lowell, where he learned lessons not taught at seminary.

“In our Lowell parish most immigrants were Southeast Asian, and they had nothing,” he recalls in his office at St. Teresa. “They were sleeping on floors, and we hustled mattresses, beds, any furniture. We had access to cheap government surplus in Taunton, but we needed an inexpensive way to move it, and I thought, maybe a tractor-trailer.”

Driving a tractor-trailer is another lesson not taught at seminary, so Fr. Conway found a junkyard where he could practice on a 27-footer so decrepit the passenger seat was a folding chair. Because the truck would not qualify for a sticker, the owner, an ex-cop, got in touch with a guy who finagled a sticker.

Alas, however, Fr. Conway flunked the driving test.

“The cop said, ‘I’d give you the license, Father, but my boss has been watching you knock over all these orange cones.’ So he sent me to a guy in East Boston, and after a few lessons, I passed.”

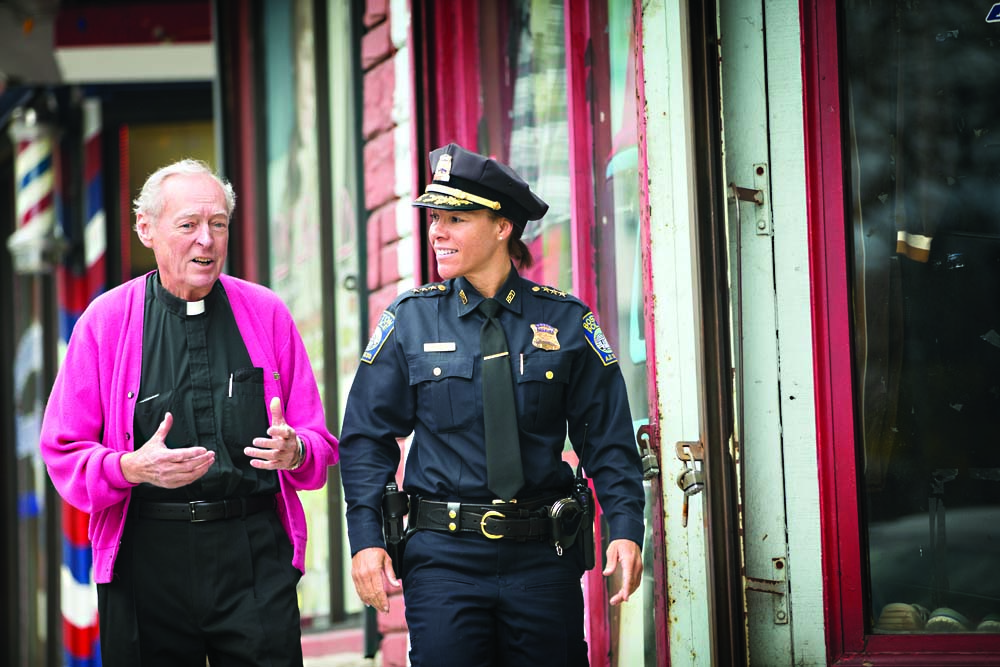

Nora Baston, now a superintendent in the Boston Police Department who heads up the new Bureau of Community Engagement, has long worked with Rev. Conway as they pursue an improved quality of life on inner-city Boston’s streets. “Father Doc is being far too modest in saying that all he does is walk the streets,” said Baston in 2014. “There’s so much more to the daily life and charitable work of thistruly remarkable human being.” Tom Kates Photography/for BC High web site and publications.

He cannot be the first priest to have wondered whether seminary might have better prepared a young priest to run a big parish by dropping one course in, say, the Pentateuch, and adding a course in – plumbing.

In Lowell, Fr. Conway said, “the equipment was old, but we had a plumbing-heating guy in the congregation who gave me lessons in using alligator clips, wired together, to jump-start the boiler and also in how to drain its water.”

The seminary might have dropped that course in Liturgical Chants in favor of a class in conflict resolution, because parish priests run into conflicts every day. Fr. Conway’s docility camouflages a tenacity against anyone taking advantage of God’s churches, and here’s an example:

In Newton, at Our Lady Help of Christians Parish, Fr. Conway was troubled by a parishioner who parked illegally every day in church lot, making it difficult to plow, so he left a note telling the man not to park there.

“The guy said, ‘But I’m in the parish.’ I said, ‘Then, you get our report and know the average weekly contribution is $2?’ Yeah, he said, and so I told him, “You’re telling me that for two bucks a week, you want three priests, a heated church, and free parking in Newton? You gotta be crazy.’ Well, he hung up, but he never parked there again. I can be a son of a bitch.”

After assignment to Concord and then Shirley, Fr. Conway was assigned to St. Margaret’s in Brockton, home to so many Cape Verdeans that he enrolled in a course to study Portuguese.

Another class not taught in seminary is how to handle inspectors who arrive on Friday to shut down a decrepit Brockton church.

The conversation was brief.

“You’re not closing this church,” said Fr. Conway.

“Oh, yes we are. We’re going to put a notice on the door.”

“I’ll take the notice down.”

“We’ll chain the door.”

“Then I’ll break the chain. We’ve got Mass on Sunday and a funeral Monday, and I’m gonna bury the guy out of this church.”

Thanks to that defiance, Mass was celebrated Sunday and the funeral Monday, but eventually, the diocese closed the church rather than invest a million dollars in repairs. In the interim, and with approval of the diocese, Fr. Conway arranged for Roman Catholic Masses, weddings, and funerals, to be held at the neighboring Lutheran Church, an ecumenical collaboration unheard of at the time.

“When the closing of the parish was upon us, we had $2,000 in the bank, and the parish council met for a regular meeting, then reassembled across the street at the Cape Cod Café, where a decision was made to blow the money on a big parish picnic, which we did.”

•••

For Fr. Conway, the next stop was Dorchester, St. Ambrose, and needing to preach in Spanish, he took lessons from a secretary.

“The first time I preached in Spanish without notes, I was talking about the parable of the mustard seed, but I couldn’t remember the word for it. I shouted, ‘What’s the Spanish word for mustard seed?’ Nobody understood, so I gestured, ‘You know, the stuff you put on a hot dog?’ And everybody yelled out, ‘Semilla de mostaza.’"

At a time in America when enmity has displaced comity, Fr. Conway navigates the poor neighborhoods with the tact of Jesus, and no one is more in awe of his skill than Boston’s new commissioner of police, William G. Gross.

“Fr. Conway is one of my favorite people in the world. I met him after a controversial shooting near Uphams Corner. The neighborhood was upset, but when I saw him talking to kids, I liked his demeanor, his candor, and I thought, ‘Wow, here’s a priest who doesn’t hide behind the pulpit, but goes into homes of gang members and speaks to Cape Verdeans in Portuguese, and in his duty to God, he’s tenacious, a real bad ass.”

After the nomadic years, Fr. Conway has settled into what may be his most productive ministry. Technically retired, he works a full week, officiating at services and interacting with parishioners in an area that encompasses half of Dorchester, Boston’s most diverse neighborhood (Pop. 124,000).

“I fight with Boston College High School all the time. There’s a teacher who asks me to walk her kids around the parish. Nora Baston comes with me. She’s a superintendent with the police. We walk Bowdoin Street, and I tell the students, ’I don’t’ know what you pay for sports equipment, but kids here don’t have money for that. They struggle. They live in three-deckers, one parent, the threat of drugs and a shooting on the streets every week, for crying out loud.”

“After one tour, I got a letter from a junior at BC, Ryan Murray of Scituate, who said the stories about drugs, gang violence, shootings, and domestic violence had touched his heart. “I highly admire your work of trying to bring the community together through block parties … because they aren’t blessed with the privacy of huge backyards like other people have.”

•••

“Rents for a two-bedroom start at $1,800. How do these people survive? They depend on extras. We run a food pantry twice a week. We’ve got people coming out of a family shelters, and they get into an apartment under Section 8. We went into one new apartment and all they had in the kitchen was two pots, one for beans, one for rice.

“So we made a list: plates, glasses, bedding, a bathroom plunger, and sent it to parishes and said ‘Help us.” We collect the stuff in a garage behind St. Peter, and we send word to shelters for people to take what they need.”

Capt. Jack Danilecki, a night commander with the Boston Police who met Fr. Conway 12 years ago in Roxbury, describes him as an inspiration.

“A hot summer night, eight o’clock, and he’ll call to say we should walk the neighborhoods. I’d moan, ‘oh, c’mon, Doc,’ but I couldn’t say no. So he in his collar and me in uniform, we’d walk tense neighborhoods and he’d talk to kids bad to the core. Having Doc in my life makes me a better man.”

•••

The tales Fr. Conway tells are not always flattering to clergy.

“In Hyde Park. I was with a priest who loved the horses. So, we get a call from the State Police because they found this little black box at Suffolk Downs, the racetrack, on Good Friday. ‘Yeah,’ the priest told the cops. ‘It’s my Mass kit. After services, I thought I’d catch a couple of races.’"

Fr. Conway is bold enough to disagree with the Vatican on controversial issues, like women as priests.

“The church should operate like the missions. My sister was in Peru as a nun, in prisons and hospitals, and she told me that many priests in missions have a “housekeeper,” and people don’t care. Women as priests? We could adjust.”

Along with many priests, he was in the front lines of Boston history during the busing crisis. As the only white person aboard a bus bearing

black youngsters to school in South Boston, he heard the hateful language and heard the rocks pinging off the bus. “I felt so bad for those kids, and for the cops, too, because people turned on them.

At 11 o’clock Mass at St. Teresa, before a magnificent altar of wood, stone, and marble, where candles flickered and morning light shimmered through stained glass windows onto sprays of Autumn flowers, Fr. Conway delivered a brief homily on family life in words of comfort, neither condemnatory nor demanding.

“The breakdown of family is probably the biggest problem in our society … In St. Peter Parish in 1945, there were 180 weddings. Last year there was one, and the year before, none … the greatest support for marriage is dependence on God through prayer and worship … ask God to be part of your marriage and family.”

Sitting on the sidewalk, Arthur Gerald is dining on what he identifies as Chinese chicken, and sitting in his lap is his great granddaughter, Zamira Alexander, 3, who offers her plastic fork with a morsel of chicken to Fr. Conway. “No, you have it,” he says, and then whispers to Gerald, “Don’t let her drink any of that,” he says, pointing to plastic cup with alcohol. Boston Police photo

On an hour-long walk along littered Bowdoin Street, he visits the usual commercial enterprises, beauty parlors, fast food joints, popup “universal” churches behind grated windows, and the occasional exotic establishment like Cesaria, where stewed goat with yucca is served along with live Cape Verdean Creole music.

Teenagers wave from across the street. At Johnny’s, barbers leave customers in the chairs and come to the door to greet Fr. Conway. Sometimes he has to speak above flashy convertibles blasting cacophonous Caribbean music.

Here are highlights:

• “That house,” he said, pointing to a three-decker, “a girl accused her mother and stepfather of bullying, and so the girl moves in with her grandmother in Charlestown. So I get her a job with the city, and when she finishes her application, she asks me: ‘Will they take you if you’re pregnant?’ Well, she had twins. The father was a drug dealer. She was 15 years old.”

• An older man interrupts the tuning of his guitar, and grasps Fr. Conway’s hand, pressing it to his forehead, a Portuguese bid for blessing.

• Fr. Conway leans down to a schoolgirl tapping her cell phone. “Did your boyfriend text you back?” She looks up, suspiciously, then laughs. “I ain’t got no boyfriend.”

• “We had a shooting here, a guy was shot right through that door.”

• Sitting on the sidewalk, Arthur Gerald is dining on what he identifies as Chinese chicken, and sitting in his lap is his great granddaughter, Zamira Alexander, 3, who offers her plastic fork with a morsel of chicken to Fr. Conway. “No, you have it,” he says, and then whispers to Gerald, “Don’t let her drink any of that,” he says, pointing to plastic cup with alcohol.

Richard Conway never had a second thought about being a priest, but what else might he have done?

“If I had been thrown out of seminary, a strong possibility, I would have taught political science. Philosophically, I’m a Bill Buckley Republican, and for president, I wrote in ‘Jesus Christ.’ “

Having survived triple-bypass surgery, he jogs several times a week to keep his weight at 155, but at 80, the thought of death is never far off, and he’s planned his funeral.

“If I get shot, then my funeral will be at St. Peter, with dinner at the teen center, and if I die of natural causes, it’ll be at South Weymouth, because they have a downstairs where you can have dinner and an open bar.

“The music will be the “March of the Hebrew Slaves” from “Nabucco,” he says, humming a few bars. First reading is from the prophet Micah, about walking with the Lord, and the Gospel from Matthew, about separation of sheep and goats.

“For the program, most people use a picture of themselves, but I’ve chosen a formal photograph of my parents, my siblings, and me, because, without family, where the hell are you?”

Asked about the first paragraph of his obituary, which will sum up his life, he demurs from mentioning his many achievements.

“I would hope it acknowledges that God was good to me.”

Jack Thomas was a reporter, editor, columnist, and ombudsman during a 40-year career at the Boston Globe.