January 18, 2017

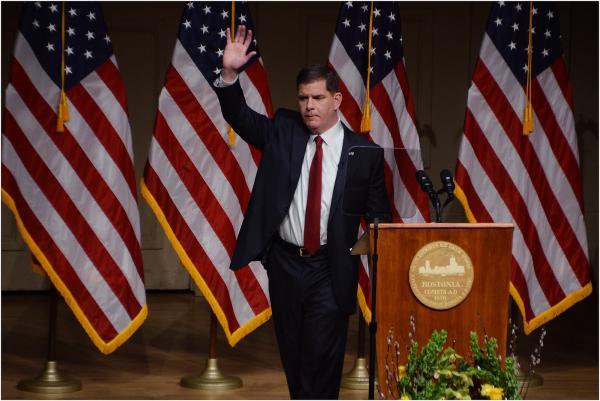

Mayor Martin Walsh waved to the crowd in Symphony Hall on Tuesday evening. Chris Lovett photo

Mayor Martin J. Walsh gave a rousing account of his administration’s first-term accomplishments to a receptive audience of nearly 1,000 civic and political leaders on Tuesday night at Boston’s Symphony Hall.

The mayor’s third State of the City address moved well into campaign rally terrain in its closing moments as the 49-year-old incumbent pledged to “fight for our values— whatever happens nationally.”

The shadow of Friday’s installation of Donald J. Trump as president was not the only political challenge that loomed as Walsh mounted the stage Tuesday night. Just feet away sat City Councillor Tito Jackson, a former political ally who last week formally began what promises to be a spirited challenge in this year’s municipal election.

Walsh’s speech was dense with the tick-tock of achievements that will no doubt be the core of his re-election bid: an overall unemployment rate that has hit a new low on his watch at 2.6 percent; a booming city with 30,000 more residents and 19,000 new homes over the last three years; and a falling crime rate.

“We’ve made historic progress, and we’re just getting started. Together we’ve built the foundation. Now we’re ready to soar.”

The speech crystallized education as the mayor’s “big ticket” item: He pledged to spend $1 billion over ten years to “invest” in Boston’s school buildings. He proposed legislation that would allow for free pre-kindergarten for the city’s 4 year olds — a plan that depends on tourist tax dollars and approval from the state Legislature.

Walsh touted achievements in the public schools that generated justifiable enthusiasm from the crowd, which was— as always— heavy with city employees. Chief among them: a deal with the city’s unionized teachers that extended learning time.

“We extended the school day, giving kindergarten through eighth grade students 120 more hours of learning time, or the equivalent of 20 added school days a year,” he said. Walsh also noted that 725 additional students have been enrolled in pre-K.

The evening’s loudest and most sustained cheers came when Walsh saluted two Boston policemen — Richard Cintolo and Matthew Morris—who were shot and seriously wounded in East Boston last fall. Both men survived and were greeted with a standing ovation.

Walsh addressed the subject of public safety with a reality check on his own report card: While overall violent crime— as calculated by Boston Police— has dropped some nine percent in the last three years and shootings decreased by six percent in 2016, Walsh said “the work is far from over. We had 45 homicides in our city last year. That’s unacceptable. One is too many. And zero is our goal.”

Walsh received a standing ovation— one of four on the night— as he referenced the creation of so-called “Neighborhood Trauma Teams”— which the city heralds as a new approach to coordinating “immediate response and sustained recovery for all those affected” by violence.

Walsh also highlighted the resurrection of the Boston Police Cadet Program— noting that the current crop of aspiring police trainees were seated prominently in the hall’s balcony perch on stage left. He noted — again to a standing ovation— that the class is “the most diverse ever, with 70 percent people of color, 33 percent women and 100 percent Boston residents.”

There were notable omissions in the mayor’s remarks.

Development and the planning essential to its transformative impacts on neighborhoods like Dorchester— was a scarce commodity. Nowhere in the speech could be found any reference to the city’s official planning arm— the Boston Planning and Redevelopment Agency, or BPDA— the successor agency of the BRA, which underwent a re-branding effort last year.

There was no specific mention of any of the planning initiatives aimed at spurring redevelopment in Jamaica Plain or South Boston— both undertaken by the BPDA last year. (In fact, the mayor dropped a line referencing those planning activities from his delivered speech.) Nor did Walsh reference an important Dorchester element included in his 2016 speech: plans to launch a similar initiative in Glover’s Corner, the heavily industrial crossroads of Dot Ave and Freeport Street.

Walsh referenced the hyper-active nature of the boom when he noted that “We advanced 35 million square feet of new living and working space spanning every neighborhood of our city. Women and men are hard at work building $6.5 billion worth of it right now— from Brighton to Hyde Park.”

Walsh boasted that his administration’s long-term planning process – dubbed Boston 2030 – made Boston a city “with a plan…for the first time in half a century.”

He repeatedly invoked the Fairmount Line as a priority project— both as a transportation node and as a potential job creator. “We’re going to make the Fairmount Line a jobs corridor, with affordable housing, through the heart of our city, from Newmarket, to Roxbury, Dorchester, Mattapan, Hyde Park, and Readville,” the mayor said, without giving any specifics of how that goal might be accomplished.

As Walsh hurried through his final paragraphs to beat a television deadline at 8 p.m., his rhetoric turned defiant as he invoked his parents’ immigrant experience in a clear rebuke to the federal threat that looms from the next president.

“We don’t just welcome immigrants in Boston, we help them thrive. And we won’t retreat an inch,” he pledged as his audience stood and cheered, a cacophony that drowned out his closing statements in the hall.

“In a time of uncertainty, we will step forward with confidence in our values,” he added. “With trust in government at an all-time low, we prove that government can work for all the people. At a time when cities must lead, Boston is the leader of cities.”

Topics: