December 4, 2014

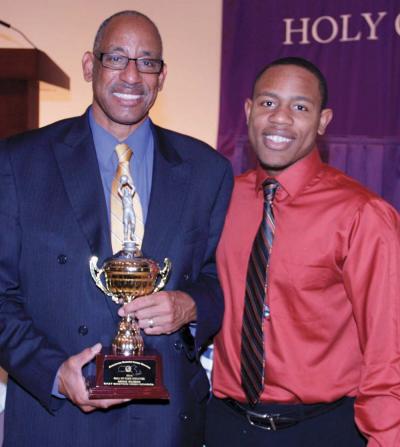

Longtime East Boston High School coach and former headmaster Michael Rubin was inducted into the Massachusetts Basketball Coach Hall of Fame on Nov. 23 at the College of the Holy Cross. At right is his son Michael, who is now an assistant coach at Quabbin Regional High School. Photo courtesy Michael Rubin

Longtime East Boston High School coach and former headmaster Michael Rubin was inducted into the Massachusetts Basketball Coach Hall of Fame on Nov. 23 at the College of the Holy Cross. At right is his son Michael, who is now an assistant coach at Quabbin Regional High School. Photo courtesy Michael Rubin

Mattapan’s Michael Rubin, a longtime coach and administrative leader at East Boston High School, was inducted into the Massachusetts Basketball Coaches Association Hall of Fame during a ceremony in Worcester on Nov. 23.

Rubin, 59, retired as the headmaster at the high school in September 2013. He stepped down as head coach of the basketball team in 2003 to assume the headmaster’s role. During his 24-year career, Rubin won four state Division 2 championships and was named coach of the year by the Boston Globe in 1985-86.

A native of Memphis, Tenn., who came to Boston in the 1970s to pursue an education at Tufts University, Rubin originally planned to go to law school. But he decided that he would devote at least one year to work as a teacher and coach.

“I said, ‘You know what, this is what the Lord put me here to do,’ ” said Rubin. “And I was good at it, relating to the kids. Back then, in 1978 and 79, we were still on the edge of the busing crisis and there was a lot of tension between black and white kids. But I wasn’t much older than them and I could play basketball, so I had an instant bond with both the black and white kids. But, it was a bad, bad scene.”

Rubin and his wife Danette, also a retired teacher, raised five children (two sons, a daughter, and two nieces) in a home on Rosewood Street near Mattapan Square. For three decades, his life revolved around his family in Mattapan and his extended East Boston family – especially the boys whom he coached year-round. Some of those boys are now adults with families and careers of their own, like Jeichael Henderson of Roxbury, who was on Rubin’s 1992 state championship team. Henderson, who now works as the assistant director of the Counseling and Intervention Center for the Boston Public Schools, was given the honor of introducing Rubin at the Hall of Fame dinner last month.

“The same man that was trying to counsel me and support me as a 14-year old kid is the same man doing that for this 41-year old man,” said Henderson, who recalled that Rubin was a hard-driving disciplinarian, but one who was ready to offer counsel every step of the way,” and long after graduation.

In the early ‘90s, amid budget cuts that disrupted the East Boston team’s travel arrangements and surging street violence, Rubin went into his own pocket to find a solution. “Coach fixed up this blue station wagon he had in order to drive myself and others teammates home after practice to avoid having to take public transportation through the gang and drug infested streets,” explained Henderson. “Insuring a safe ride home with extended time for mentorship and bonding was instrumental in our growth and development as young men.”

Rubin’s rigorous approach to coaching proved to be a winning strategy, one that was particularly welcome at a high school that had not enjoyed a successful season since 1949. His teams won 12 Boston city north titles and ten overall city titles, along with the four state banners.

“I instilled discipline and work ethic and we began to change to culture, to make sure they were at school – every day. My rule was no school, no practice, no games. We all wore a shirt and tie to away games. And, some people don’t like this, but we practiced seven days a week. And that’s how we started to turn that thing around.”

East Boston went 16-1 in 1983-84 and won back-to-back championships in ‘85 and ‘86. He won two more state titles with teams in 1992 and 1999.

“I had some talented teams that didn’t win the state championship,” said Rubin. “The players all have to buy into the team concept and into everything you are doing. Especially in the city, they have to stay out of trouble in school – on the court and off the court. When they come together as a team and are all in it for each other, that’s when you know you have something special.”

Most special for Coach Rubin, however, has been watching former players excel.

“The greatest reward is seeing my kids be successful at life,” said Rubin, who said he was “brought to tears” by Henderson’s introduction. “Because of my life circumstances, I constantly preached about the value of education to all of my players. I told them to look at my life and see what an education can do.”

Rubin was an orphan at age 11, having lost his mother at age 9 and then, two years later, his father as well. He was raised by an aunt on the south side of Memphis and excelled as a student-athlete at Melrose High School. There, he was mentored by teacher and coach Levon Bridges, whom he still considers his idol. A guidance counselor— Yvonne Greene— connected him with a program called A Better Chance, which sent Rubin to the Taft School in Watertown, CT.

That opportunity, Rubin says now, was a game-changer and put him on a track to help other less fortunate city kids. Now in his first full year of retirement, Rubin is staying busy as a consultant and board member for the Massachusetts Interscholastic Athletic Association (MIAA), the governing body that oversees student-athletics in the state. He is leading an effort to diversify the organization’s various committees, including the board of directors. He also serves as on a board that hears grievances within the Boston Public School system.

And, when he’s not “busy” being retired, Rubin still touches base regularly with many of his former players. “He was a heck of a coach, but he was also a father figure to so many of us,” recalls Henderson. “When practice ended or the season ended, he was always checking in on you. He was overbearing at times, but for good reason. He’s a big part of my success.”

Topics: