July 1, 2013

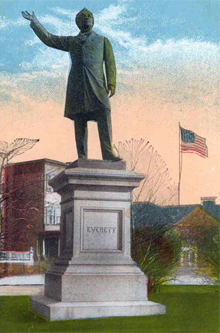

Edward Everett statue: From a turn-of-the-century postcard.Edward Everett — the name is a familiar one to Dorchester residents. If asked who he was, many people would reply that he's a guy they named a school and a square after; some would also point out that a statue was raised to honor him.

Edward Everett statue: From a turn-of-the-century postcard.Edward Everett — the name is a familiar one to Dorchester residents. If asked who he was, many people would reply that he's a guy they named a school and a square after; some would also point out that a statue was raised to honor him.

Still, a great many people might not realize just how important a figure he was not only to 19th century Dorchester, but also to the nation. Everett loomed large on the historical stage as a statesman, orator, and politician.

He was born in Dorchester on April 11, 1794, the son of a minister. From his early days, Edward Everett displayed a keen intellect, and few in Dorchester were surprised when he graduated at the age of 17 from Harvard at the top of his class. During his years there, he had served as editor-in-chief of The Lyceum, the college's journal.

His editorial and literary flair notwithstanding, Everett looked in different career directions. Although he evinced an interest in the law, he took the advice of renowned cleric and orator Joseph Stevens Buckminster, who convinced the young Dorchester man to study for the ministry. Everett, before he was 20, ascended the pulpit of the Brattle Street Unitarian Church, and his polished, erudite sermons garnered attention all over the region. As his theological reputation swelled, in 1814 he wrote a tome entitled Defence of Christianity.

Everett began to grow restless in his ministry, casting about for some other profession that would appeal to both his intellectual and oratorical gifts. He left the pulpit scarcely a year after climbing it and returned to Harvard not as a student, but as a young professor of Greek literature in Harvard College. To further his fitness for the post, he traveled to Europe for nearly five-years' worth of study. He came back to the classroom and carved out star status as one of the college's preeminent educators.

Only 25 years old, he became the editor of the prestigious North American Review in January 1820, overseeing it transformation into an influential quarterly publication and contributing a range of articles and essays during his four years at the review's helm. He honed a taste for political issues in the post, and in 1825, he ran for Congress and won the first of his five consecutive terms representing the people of Dorchester.

In Washington, Everett established himself as a strong supporter of President John Quincy Adams and then as a vociferous foe of Adams's successor, the fiery Andrew Jackson.

To the admiration of most of his Dorchester neighbors and constituents, Everett did not shy away from any of the hot-button issues facing the young republic. His firsthand knowledge of Europe led to his appointment to the Committee of foreign Affairs, and he similarly established himself as a mover and shaker on such committees as those fighting over such crucial matters as Indian Affairs, the Bank of the United States, and, increasingly, abolition versus slavery.

Everett proved a dogged opponent of Jackson's determination to forcibly remove the Cherokees and other tribes from ancestral lands granted them by federal treaties, and march them off to barren tracts to the West. Everett's battle against the infamous "Trail of Tears" (the forced removals) was a losing one, but one that testified to the Dorchester representative's integrity and compassion.

In 1835, Everett brought his political gifts back home by winning election to the governorship of Massachusetts, evoking a deep sense of pride in his "old stomping grounds," Dorchester. He negotiated a number of landmark bills into state law: the creation of the nation's first board of education; the first scientific survey of a state; a criminal law commission; and key economic measures that helped keep Massachusetts from financial ruin during the nationwide Panic of 1837.

Despite his outstanding record as governor, Everett lost his bid for reelection by one vote —out of more than 100,000 cast.

In the following spring he made a visit with his family to Europe. In 1841, while residing in Florence, he was named United States minister to Great Britain served brilliantly in the position until the accession of James Polk to the presidency in 1845.

Once again, the Dorchester statesman returned home, this time serving as president of Harvard from January 1846 to 1849. In October of 1852, President Millard Fillmore appointed Everett secretary of state to replace Everett's late friend Daniel Webster in the slot. Everett held the position until 1853, when he returned to run for one of his home state's U.S. Senate seats.

Everett won the election, but in May 1854 his suddenly waning health forced him to resign upon the urgent advice of his doctors and enter private life. However, Everett's idea of private life burgeoned into a time that placed him front and center on the political landscape. In Dorchester, he was a welcome presence, delivering memorable speeches at events including the town's 4th of July celebration in 1855, but it was his orations pleading for North and South to back away from impending war that garnered him national attention — both acclaim and aversion. Against his doctors' orders, he became the 1860 vice presidential candidate of the ill-fated Constitutional-Union party, running on the ticket with John Bell; the duo garnered 39 electoral votes, losing badly to a gangly Republican named Abraham Lincoln.

Everett threw all of his energies behind the Union once the Civil War erupted at Fort Sumter in April 1861, and in an elegant 1863 speech that would become a historical footnote, he delivered an address at Gettysburg some weeks after the savage battle. Then other chief speaker that day was President Lincoln.

Everett took the podium of a January 1865 public meeting in Boston to raise funds for the poor and returned home chilled and coughing. The cough lingered, and a fever soon accompanied it. On January 15, 1865, the Dorchester man whose brilliance, statesmanship, and speaking skills had made him a towering figure of the era died.

Today, Edward Everett's name lives on in the Dorchester landmarks recalling a man who embodied the highest standards of community and public service.

This article originally appeared in the Reporter in 2003.