October 14, 2022

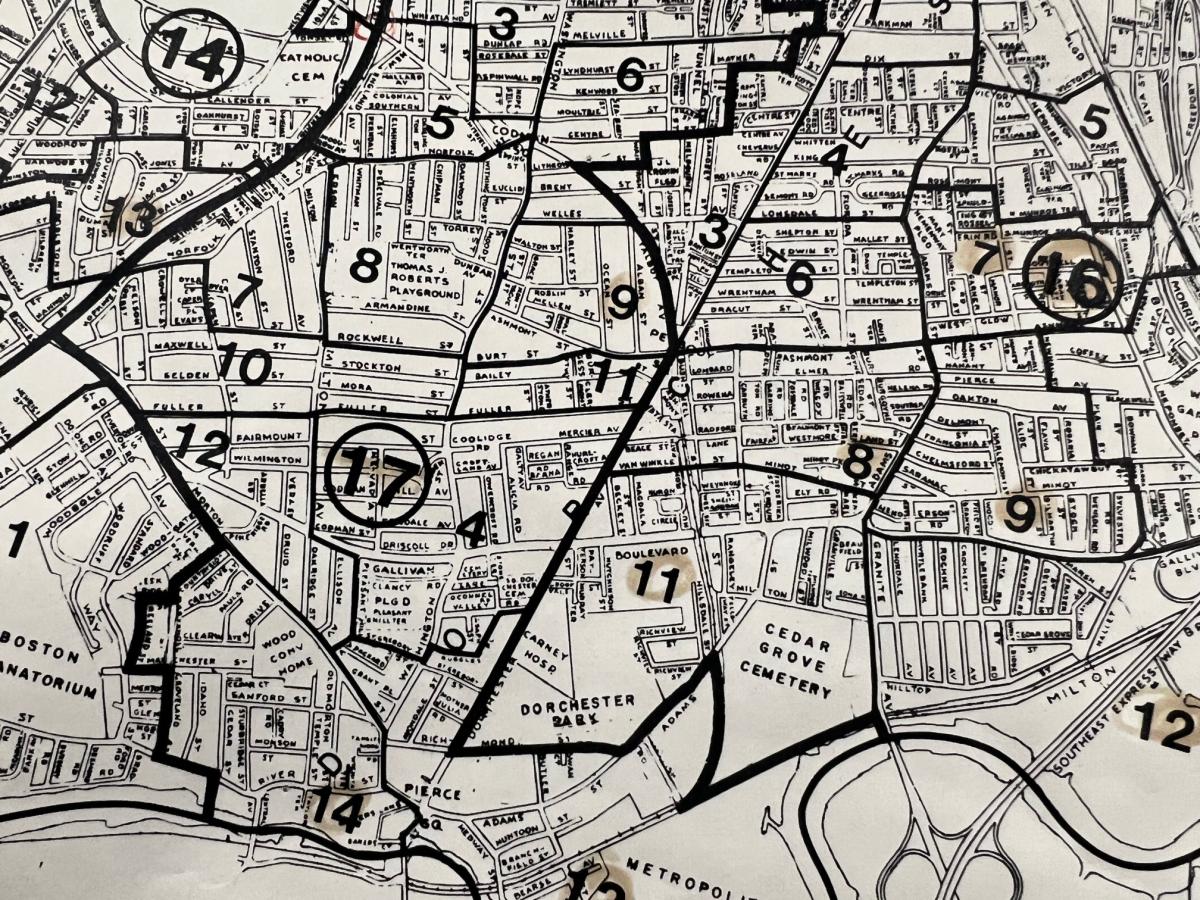

The debate over how to redraw district lines for Boston’s nine city council seats is reaching its climax this month. It’s never an easy process and this year’s work has been complicated by an intense political season. Ricardo Arroyo, the original chairman overseeing the decennial shuffle, was busy running for district attorney. Then, he was stripped of his duties amid a pre-primary scandal that led his one-time ally, Council President Ed Flynn, to suspend him from leadership with just six weeks left to figure out a compromise map.

It has fallen to his vice chair, Liz Breadon of Brighton, to carry on the work over objections of councillors of color, who contend that Arroyo should be restored to this seat.

This week, there are four competing maps in front of a deeply fractured council. There may, in fact, be a fifth in play if Dorchester’s Frank Baker follows through on his pledge to offer his own.

Baker’s District 3 is the seat most likely to see significant change, in part because the 2020 Census showed a loss of thousands of residents in D-3, necessitating a shift in precincts to pick up population. Each district, ideally, should average about 75,000 residents. Flynn’s Southie-based seat— D2— for example has gained many thousands more.

Baker is understandably unhappy that one map— offered by Arroyo and Tania Fernandes Anderson— would stretch D-3 from the Neponset River to Copley Square. It’s an unwieldly, unsatisfactory proposal that lumps together disparate communities with often-unaligned interests.

However, Baker’s own logic around how to organize District 3 is also seriously flawed. “We have very clear parish boundaries that I believe should be respected,” he argued at a hearing last week.

There are many reasons why the parish dynamic has no place in a present-day discussion about political redistricting. For one, most residents who live in 2022 Dorchester aren’t Catholic churchgoers, including, by the way, many Catholics.

The archdiocese itself has closed or merged multiple parishes and churches in the last decade while others — specifically St. Brendan—are fighting to just stay alive. St. Gregory parish— while centered at the church building in Lower Mills— includes large sections of Milton in its catchment area. And Baker himself hails from Columbia/Savin Hill area and was a parishioner at St. Margaret’s, which no longer exists as a parish. (The church building remains open under a new parish name, Blessed Mother Teresa.) St. William parish, which many people in his neighborhood attended decades ago, closed in 2004 and is now a Seventh Day Adventist congregation.

Are there still people who, when asked where they are from, will respond with a parish identity? For example: “I’m from St. Mark’s. She’s from St. Peter’s.” Sure, but it’s a dwindling slice of what is now a multicultural stew of people from many different faith traditions. Many more people relate to the neighborhoods by villages or even T stops than by church sanctuaries that may or may not still exist.

Figuring out how to align communities of interest into coherent districts is difficult enough. Dorchester’s villages have urgent common concerns that argue for keeping many of its precincts intact under District 3 or District 4, now represented by Brian Worrell. That exercise is hindered, not helped by leaning into decades-old parish “lines” that have little context or meaning in 2022 Boston.

Topics: