January 15, 2020

City Councillor Lydia Edwards of East Boston thinks that the time has come for Boston to simplify and streamline its governing document, commonly known as the city charter. This week, she filed an order that requests a hearing to get the process moving.

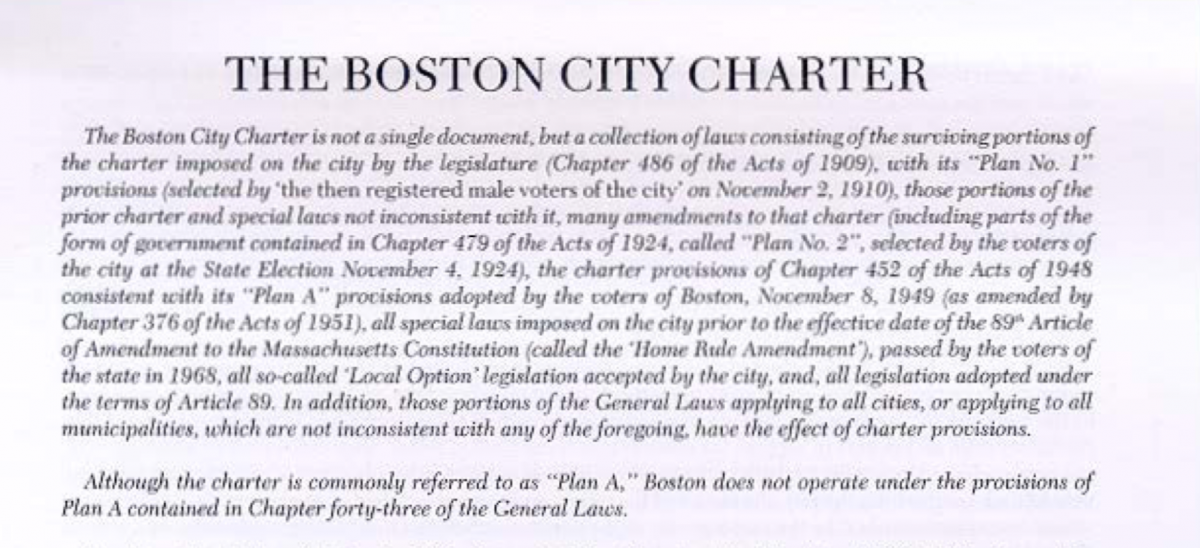

In point of fact, as Edwards argues, the city doesn’t really have a single “charter.” Its functions are governed by a “patchwork of special acts rather than a uniform document,” a result of what Edwards and others critique as an early 20th century power-check aimed at curbing the climb of the then-ascendant immigrant Irish Catholics. Now, as a new wave of women and people of color move into the majority, the same might be said of the modern Boston.

“The power dynamic of the city is in the charter and if that doesn’t change, all of the window dressing in the world means nothing,” Edwards told the Reporter this week.

It’s not just the “strong mayor” setup of city government that motivates Edwards and her like-minded colleagues on the council. The composition of the city’s zoning and licensing boards, she notes with disdain, can only be changed with state legislative approval. The city must seek Beacon Hill consent — through home rule petition— to levy a local tax on luxury real estate transactions, for example. The fact that many suburban lawmakers are frequently at odds with the capital city’s goals makes it very difficult for the city’s leadership to implement the changes they want to see happen.

“Right now, all we can do is file another petition and hope it passes, which they so often do not. I’m sick of the patchwork and piecemeal approach. We should have it all in one document and the power to amend it,” she argues.

This is far from the first time that the council has sought to shake up this old frame. District 3 Councillor Frank Baker has headed a special committee charged with reviewing the city’s charter since 2014. Prior to that, former Councillor John Tobin of West Roxbury led a similar charter reform committee. Neither one prompted any concrete movement.

You have to look back to 1991— when the Boston School Committee was converted from an elected body to a mayorally appointed one— to find the last significant change to city government. Before that, 1983 brought us the 13-member council body we have today with nine district councillors and four at-large members.

Former city councillor Larry DiCara, a longtime proponent of reviewing and updating the charter, was part of a team of people who published “Boston Unbound,” a 2004 report commissioned by the Boston Foundation that made the case for modernizing the charter. He’d be a solid choice to help draft a new charter— and DiCara says he’s more than willing if the larger political will is behind it.

“Compared to first half of the 20th century, Boston has been very well run,” DiCara notes. “The bond rating is great, it is booming. But, Boston has far less power than other comparable cities. I would argue that’s ridiculous. The city generates a quarter of state’s revenue and its 2020 and we should have the rights to do parking tickets and [set the] speed limit. That all goes back to the Yankees not wanting the Irish to be the ones in charge.”

It’s true that any changes to the charter would also need the approval of the mayor — who is “reviewing” Edwards’s hearing order— and the Legislature. But the city council is key here. It’s more progressive and reform-minded than earlier incarnations. And this mayor has shown a willingness to collaborate with them. The council class of 2020 — infused with fresh, progressive blood— could very well make a serious run at charter reform this session.

- Bill Forry