March 8, 2017

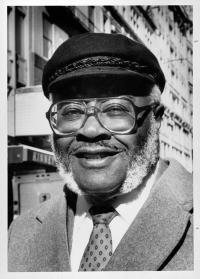

Kenneth Guscott: Photo courtesy Bay State BannerThe sudden death of Kenneth Guscott, who perished in a house fire at his Milton home on Monday morning at age 91, is a tragic end to an extraordinary life. The fire, which Milton officials say was caused by an electrical problem related to a heater, also claimed the life of Guscott’s father-in-law, 87 year-old Leroy Whitmore, compounding the tragedy for the family.

Kenneth Guscott: Photo courtesy Bay State BannerThe sudden death of Kenneth Guscott, who perished in a house fire at his Milton home on Monday morning at age 91, is a tragic end to an extraordinary life. The fire, which Milton officials say was caused by an electrical problem related to a heater, also claimed the life of Guscott’s father-in-law, 87 year-old Leroy Whitmore, compounding the tragedy for the family.

Ken Guscott, an Air Force veteran who served in World War II, spent his whole life battling for equal rights for all Americans. More recently, he was heralded as a pioneer in the business community. His family’s company, Long Bay Management, owns apartment buildings throughout Dorchester, Roxbury, and the South End.

Notably, Ken, his brothers, and his daughter Lisa were the driving force behind One Lincoln Street, a downtown high-rise that was the first of its kind developed by an African-American team.

But his achievements in the boardroom represent just part of his legacy. Kent was a pivotal leader in Boston’s ongoing struggle to fight discrimination, especially for people of color.

“When the history of modern-day Boston is written, Ken Guscott’s name will appear among the great leaders as one of the true architects and developers of social justice, equity, and progress for all its citizens,” said Louis Elisa, who served as the Boston NAACP president from 1989 to 1994.

Ken served as president of the Boston Branch of the NAACP from 1963 to 1968 and was a key voice in confronting Jim Crow-era bigots and their enablers here in Boston. Under his leadership, the NAACP was instrumental in desegregating Boston’s schools and beaches, which were flashpoints for conflict in the 60s.

He also led voter registration drives that were credited for mobilizing black voters to elect the first city councillor of color, Thomas Atkins. And Ken’s work helped to counter the bigoted politics of the Boston School Committee and its leader, Louise Day Hicks. Under his stewardship, the NAACP was viewed as critical to her loss to Kevin White in the mayoral election of 1967.

In 1965, Ken presciently warned: If Boston, like the South votes “to keep the Negro in his place, the city will be voting for those who build their political careers on saying ‘No’ to the Negro.”

He led sit-ins and marches and synchronized Boston’s support of the March on Washington in 1963, which he called “the turning point in the field of civil rights” in a 1968 article in the Boston Globe.

Back home, his tenacious opposition to de facto segregation in Boston’s public schools resulted in legislation to uproot racial imbalance that ultimately led to the court-ordered desegregation plan that roiled the city in the 1970s.

Bettye Robinson, another NAACP leader from the 1990s, called Mr. Guscott “a warrior and fighter, and they do not come any better. Along with Melnea Cass and Tom Atkins, he always had me working. I have wonderful memories and learned so much from working with the NAACP under Ken Guscott. We were a family,” she said.

Michael Curry, who served as NAACP Boston president until last year, said gthat Mr. Guscott “spent a lifetime recruiting, mentoring and supporting young leaders, and I’m honored to be among them.”

Ken Guscott’s love for Boston was rivaled only by his fondness for his parent’s homeland, Jamaica. He relished his work as an honorary consul for Jamaica here in Boston in the 1990s and 2000s and traveled “home” frequently to promote stronger bonds between the US and Jamaica.

But it is here in Boston that his legacy will be forever cemented into our civic firmament. In this moment of loss, we should recall Ken Guscott’s defiant posture toward the great tyranny of his time— and take solace in knowing that his inspired leadership made our city and state a better place. We owe him a deep debt of gratitude.