April 12, 2017

Sean Ellis

Sean Ellis

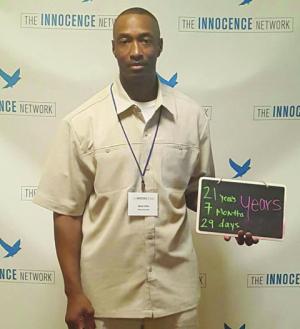

Sean Ellis brings his story to Innocence Project conference

Sean Ellis, a former Dorchester resident, recently traveled to San Diego as a guest of The New England Innocence Project to participate in the annual conference of the Innocence Network Conference, an affiliation of 56 US and 13 non-US organizations with a mission of “providing pro bono legal and investigative services to individuals seeking to prove innocence of crimes for which they have been convicted, and working to redress the causes of wrongful convictions.”

More than 550 people attended the gathering, including 150 exonerees, and Valerie Jarrett, former White House advisor to President Obama, was the keynote speaker.

Ellis, who was accompanied by his sister, Shar’Day Taylor, a state of Massachusetts social worker, brought a singular experience to the conference: In 1995, despite his insistent declarations of innocence, he was convicted – at his third trial after the first two resulted in hung juries – of the 1993 murder and armed robbery of a Boston detective.

A 1998 motion for a new trial and a subsequent appeal were both denied, and he ultimately spent more than 22 years in prison until the Boston defense attorney Rosemary Scapicchio took up his case, and, in 2015, convinced a Suffolk Superior Court judge that, due to police misconduct and prosecutorial lapses, he deserved a retrial.

Ellis was quickly released, and now, at age 43, he is free on bail awaiting word from Suffolk County prosecutors on a date for his fourth murder trial. Ellis needed a court’s permission to travel out of state and temporarily remove the GPS ankle bracelet that he wears 24/7. Chief prosecutor Edmund Zabin objected to his travel, telling the hearing judge, “He never should have been let out” – this despite the unanimous affirmation of Ellis’s wrongful conviction by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in 2016.

For all that, the trip was a thrill for Ellis; for one thing, it marked the first time he’d been on an airplane. He excitedly filmed the takeoff on his smartphone.

“It was the first time I’ve felt free since I’ve been out,” he said.

“There was never a dull moment” for him at the conference, said Ellis, who attended such workshop sessions as “Social Media: Power, Presence & Purpose.”

At the “Moth Storytelling” workshop, he and more than two dozen other released inmates were allotted five minutes each to tell their stories onstage. Sean, by now a seasoned speaker at various forums around Boston, found this a huge challenge. How to compress all he’d gone through into five minutes?

He focused on two life-changing days: The first was September 26, 1993, when he was 19. He walked into a 24-hour drugstore in the early morning hours to buy a box of Pampers for his cousin, and “one and a half weeks later I was arrested for murder.” On that day at dawn, Boston Police Detective John Mulligan, who was guarding the store from his SUV parked in the fire lane outside, was murdered as he slept in in the driver’s seat of the vehicle.

The second day was when his lawyer brought to him in prison the FOIA information that had begun arriving, after an 8-year wait, detailing crimes committed in the 1990s by John Mulligan and three other Boston detectives. The surviving trio investigated Mulligan’s murder and marshaled every piece of evidence used against Ellis. That the police officers had been leading double lives – conducting a longstanding on-the-job enterprise of falsifying warrants and robbing drug dealers – made Ellis realize there was a bigger story going on behind the scenes.

The courts agreed. As Chief Justice Ralph Gants wrote in the SJC’s 2016 ruling, “We did not know at that time that these detectives had been engaged with the victim in criminal acts of police misconduct as recently as seventeen days before the victim’s murder. The complicity of the victim in the detectives’ malfeasance fundamentally changes the significance of the detectives’ corruption with respect to their investigation of the victim’s murder.”

Ellis concluded his San Diego talk by admitting that while he had lost faith in the system over the course of his long imprisonment. he never lost faith in himself. “They could not take that from me,” he said. “As he saw it, in prison offered two choices: either be consumed by the negative environment or grow. I chose to grow.”

That he did. He earned a paralegal degree by correspondence course, got in touch with his emotions through the prison’s “Jericho Circle” chapter (“In prison you grow callous,” he says), and received counseling training in the “Second Chance” program of mentoring youthful offenders.

Asked what he’d like people to know about his conference experience, he pointed to a photo on the backdrop of the stage proclaiming a total of 2,953 years of wrongful incarceration endured by those telling their stories. Even so, “The stage had a certain feeling to it,” he said. “It was of love, compassion...maybe even warmth. It felt comforting and warm. There was none of the tension of prison. It was just beautiful.”

Ellis wants to share the lessons he drew from attending the conference: “This feeling can exist” in the hearts of people who’ve been wrongfully imprisoned, people with every right to hold unrelenting bitterness against the system. In short, people, like himself, who’ve chosen to grow.

Elaine A. Murphy, a former Boston teacher, is a Senior Justice Fellow at Brandeis University’s Schuster Institute for Investigative Journalism and author of the website justiceforseanellis.com.