May 7, 2015

54th Massachusetts Infantry Volunteers: Lt. Benny White and 1st Sgt. Gerard Grimes on Meetinghouse Hill on Saturday. The Dorchester Soldiers Monument stands to their left. Photo by Bill ForryMembers of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment— men who portray the real-life soldiers of the celebrated Civil War unit— camped out on Meetinghouse Hill for several hours last Saturday. The living history event was intended to call attention to the 150th anniversary of the end of the war, which continued to sputter out over weeks and months after the climactic surrender of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in April 1865.

54th Massachusetts Infantry Volunteers: Lt. Benny White and 1st Sgt. Gerard Grimes on Meetinghouse Hill on Saturday. The Dorchester Soldiers Monument stands to their left. Photo by Bill ForryMembers of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment— men who portray the real-life soldiers of the celebrated Civil War unit— camped out on Meetinghouse Hill for several hours last Saturday. The living history event was intended to call attention to the 150th anniversary of the end of the war, which continued to sputter out over weeks and months after the climactic surrender of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in April 1865.

It was fitting that the encampment took place at this green space— re-named in modern times for Rev. James K. Allen, the longtime presiding minister at First Parish Church across the street. The current First Parish minister Rev. Art Lavoie invited the 54th volunteers to stage the event. They pitched their tents about 40 feet from the Dorchester Soldiers’ Monument— a carved bronze and granite creation topped by an obelisk that was dedicated just two years after the close of hostilities between the North and South.

The Dorchester Soldiers Monument in Rev. Allen Park : Dedicated in 1867, it sits directly across the street from the First Parish Church. The monument itself is situated on land that was occupied by a previous incarnation of the church in the 18th and 19th century.

The Dorchester Soldiers Monument in Rev. Allen Park : Dedicated in 1867, it sits directly across the street from the First Parish Church. The monument itself is situated on land that was occupied by a previous incarnation of the church in the 18th and 19th century.

Divisive by nature, it’s no wonder that the American Civil War was called different names by different people and regions. In the south, some called it the Second War for Independence and later, the war of Northern Agression. Here in Boston, the four long years of bloodletting was popularly known as the “War of the Rebellion” and it was largely fought by citizen soldiers from rural outposts like Dorchester, which was still an independent town when southern seccessionists turned their guns on Fort Sumter in April 1861.

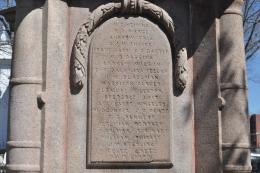

A panel on the Dorchester Soldiers' MonumentDorchester men did more than their fair share of the fighting and dying in what we now call, simply, the Civil War.

A panel on the Dorchester Soldiers' MonumentDorchester men did more than their fair share of the fighting and dying in what we now call, simply, the Civil War.

At the dedication of the Soldiers Monument in September 1867, Rev. Charles A. Humphreys — visiting from Springfield, Mass delivered an oration saluting the “one hundred martyrs” whose names are engraved on the monument. (Actually, there are 97 names in total on the monument.)

He noted: …“[I]n the late war for our national existence, with a population of only ten thousand, she furnished one thousand two hundred and seventy-three men, which was one hundred and twenty-three in excess of all calls; and of these, one hundred and twenty-seven became martyrs of liberty, ninety-seven of them our own townsmen.”

Of those 97, as Humphreys tallied, 26 were killed in battle, with another 20 dying later from their wounds. Eleven died in “inhuman” Rebel prison camps; two from accidents while in service and another 9 were unknown— apparently missing. Twenty-nine of the 97 died from disease— a statistic that was not out of proportion from the rest of the nation that saw epidemic levels of death in festering campgrounds.

The seal of the town of Dorchester is engraved into the side of the monument. Bill Forry photo

The seal of the town of Dorchester is engraved into the side of the monument. Bill Forry photo

“To-day we give them to history; but not alone to her cold and voiceless record,” Humphreys told the crowd assembled for the dedication on September 17, 1867‑ five years to the day after the battle of Antietam— still America’s bloodiest day. “We have also inscribed their names upon the tablets of our hearts, and there they shall live in a bright immortality of grateful remembrance.”

Francis P. Denny, Esq., who chaired the committee that raised funds and built the monument, spoke next. He noted that the newly hewn monument stood where the “third meeting-house erected in the town” had stood for 74 years— from 1743 until 1817.

“This tree marks the spot where the pulpit stood,” Denny recalled. “So that this is already consecrated ground, sacred as the place where our fathers assembled for the worship of God.”

“What memories are awakened as we gather here today!” Denny continued. “It was here you came to urge your young men to enlist in the army of the Union, at those earnest meetings where the word of patriotism was answered by the pledge of life for country, and whose enlistment paper contained many a name inscribed upon the roll of honor here…. How often have these rocks resounded with the measured tread of the procession bearing the precious dust of the hero from receiving its last sad honors to its final resting place! And when victory came, as come it must, it was here you welcomed home your war-worn veterans.”

The design of the monument , Denny noted, was “limited by the funds of subscription to which it was wished all should contribute rather than to have it large and exclusive.” The committee, he continued, “sought for no elaborate column, no pretentious architectural display. The structure that attempts by its magnificence to glorify the dead is meaningless.”

Perhaps invoking Lincoln’s stirring Gettysburg address, Denny cautioned, “We can add no honor to what our soldiers earned for themselves.”

Rev. Humphrey’s oration similarly sought to salute the men as a collective. He impressed upon the crowd— many of them widows or bereaved parents of the fallen— that the monument must stand testament to a greater cause, one that the still fractured union was just then trying to piece together.

“Even if our monument, besides celebrating the virtues of our heroes, should also recall the crimes of the rebels, and revive the long smothered indignation against the plotters of treason in the South, still let it stand,” Humphreys insisted. “We may forgive, but we cannot forget,— we must not forget. We owe it to our brothers not to forget their sacrifices. Upon their wasted lives we are rearing the structure of a nobler civilization.”

“May the keeping of it ever be held a sacred trust.”

Topics: