April 3, 2013

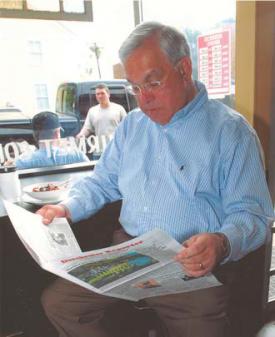

News-fix on Neponset Ave. : Mayor Tom Menino gets his weekly dose of the Reporter at the Mud House, Neponset Ave., 2007. Photo courtesy Mayor's OfficeDiligence, hard-work, and mastering the art of being underestimated were the tools Tom Menino used to establish himself in Boston politics: first as a driver, aide, and campaign manager to others; then as district city councilor for Hyde Park; and finally as mayor.

News-fix on Neponset Ave. : Mayor Tom Menino gets his weekly dose of the Reporter at the Mud House, Neponset Ave., 2007. Photo courtesy Mayor's OfficeDiligence, hard-work, and mastering the art of being underestimated were the tools Tom Menino used to establish himself in Boston politics: first as a driver, aide, and campaign manager to others; then as district city councilor for Hyde Park; and finally as mayor.

Lacking Kevin White’s polish and Ray Flynn’s emotional intensity, Menino majored in survival. Nobody ever voted Tom off the island. He enters history as Boston’s longest serving mayor. With five consecutive terms under his belt, he is the Ted Williams of Boston politics – the first, and maybe the last, of the city’s 1.000 political hitters with five straight mayoral campaign hits in five at bats.

Menino’s essential guise of being a regular guy – nose to the grindstone trying to do the right thing – proved a potent act. Make no mistake: It was an act. No one without burning ambition, laser-like focus, and the ability to maximize luck when fate broke his way, could rise and flourish as Menino did.

As mayor, Menino was an illusionist, a master of indirection. He plotted each year around three big speeches: the State of the City, a talk for the Municipal Research Bureau, and an address to the Chamber of Commerce.

The mayor’s modest speech impediment proved to be a powerful tool on these occasions. It softened up the audience. This being Boston, everyone at these events was smarter than the person they were sitting next to. Elites everywhere may be short on humility. But in Boston, watching someone fail to measure up is almost as satisfying as getting an honorary degree from Harvard. Menino always scored.

The speeches were plainspoken, shrewdly targeted, and sincerely delivered.

The applause would be heartfelt, and over the years grew to be enthusiastic.

Reactions ranged from “not bad” to “pretty good” with “excellent” becoming not uncommon. Headlines naturally followed, as did several days of analysis that ranged from silly to sage. Thus was municipal consensus established and – more importantly – adjusted and maintained.

Mayor Menino delivering his State of the City address in 2009.: Photo courtesy the Mayor's Office.Over the years, Menino delivered about 60 of these sermons. In the hours before the mayor made his official announcement that he would not seek a sixth term, I scrutinized as many of those speeches as I could lay my hands on.

Mayor Menino delivering his State of the City address in 2009.: Photo courtesy the Mayor's Office.Over the years, Menino delivered about 60 of these sermons. In the hours before the mayor made his official announcement that he would not seek a sixth term, I scrutinized as many of those speeches as I could lay my hands on.

The form was remarkably consistent: nine to a dozen initiatives, breakthroughs, and new directions per speech. That means that during Menino’s tenure he has launched about 600 ships – more or less.

The foundation upon which Menino built his mayoralty (as well as these speeches) was Boston’s sound fiscal footing, perhaps the most valuable legacy Menino leaves his successor.

Some topics, such as the seemingly intractable challenges of reducing crime or increasing school performance, made frequent appearances. But slowly and surely urban reality was hammered into line with mayoral rhetoric.

By and large, these speeches were bullet-proof: unmeasured and in some instances unmeasurable. They were the cornerstone of City Hall’s essentially successful strategy of neutering the dailies and keeping television news under control.

Who remembers the promise to cloak Boston in a new canopy of 10,000 trees? Or a new sky-high office tower in the financial district? Or the pledge to be open to new ideas and curb his famous temper? Or the pledge to guarantee a transparent casino process?

The paradox is that while critics – and even some supporters – complained that Menino was no visionary, year in and year he bared his hopes and dreams for Boston. Central to this vision, of course, was the reelection of Tom Menino.

In dreams begin responsibilities, and never during his time in office was there any doubt that Menino, and Menino alone, was in charge. There were no independent, quasi free-wheeling power players like Micho Spring or Barney Frank in White’s administration, or star administrators such as the late Bill Coughlin, who served Flynn by cleaning up the mess in the assessing office before going on to straighten out public works.

Menino installed a governance template that was purely top down. During his first two terms it proved to be less than perfect. Kevin Joyce screwed up inspectional services. Nancy Lo botched both licensing and elections. And Merita Hopkins under-performed as city solicitor.

These incidents were merely footnotes. As he usually did, Menino learned and has recruited subordinates who combine competence with loyalty, such as Bryan Glascock of inspectional services, Tom Tinlin of transportation, and Bill Sinnott, who heads the law department.

The key to Menino’s unprecedented political dominance, however, owes more to external, structural factors than to managerial organization.

The expansion of the City Council from nine exclusively at-large members to a mix of four at large and nine district councilors diluted the power of an already weak council.

The successful – if necessary – removal of the School Committee from an elected to an appointed body also eliminated a spawning ground for political challengers.

If inside City Hall, Menino was known as a ruthless micro-manger who brooked no dissent, in public the mayor was avuncular and approachable.

Due to demographic changes that date to the 1980s, before Menino was elected, Boston was growing in terms of population for the first time in forty years.

More people meant more housing. More housing equaled more construction. And more construction meant jobs.

This sort of slow and steady growth may not have helped those at the bottom rungs of the economic ladder, but it did give Boston a veneer of prosperity that escaped most cities as old as Boston.

Menino, with the heart of FDR and the brains of Martin Lomasney, Boston’s most famous and powerful political boss, knew how to play to both the city’s older, white traditional voters as well as to engage the city’s minority and growing immigrant population.

Here Menino was greatly aided by the fact that he does not appear to have a prejudiced bone in his body. His early embrace of gay rights, his consistent championing of grass-roots development in black neighborhoods, and his sensitivity to the needs of new Asian and Hispanic immigrants endowed Menino with a political safety shield far more powerful than mere charisma.

All politicians are great egotists. For most, electoral survival is the prerequisite for doing good. That Menino was able to leave the city in better shape than he found it – even after weathering the greatest financial crisis in a generation – is a tribute not only to his political and managerial skills, but also to his essential guiding moral compass.

I do think, however, that when history is able to render a more complete judgment on Menino’s 20 years in office a glaring mistake will be evident: the failure to achieve more in the most recently concluded contract negotiations with the Boston Teachers Union – especially the institution of a longer school day.

Menino has always been an incrimentalist. No doubt he was banking on achieving more during his next four years. As we all know now, there will be no sixth term. And whoever wins the mayor’s office will have to begin all over again in fighting to give Boston’s public school children the education they need and deserve.

The bottom line: Tom Menino was a good mayor, probably a great one – but he wasn’t perfect.

Peter Kadzis was for many years the Executive Editor of The Boston Phoenix. He grew up in Dorchester’s Ward 17, Precinct 12.