February 19, 2025

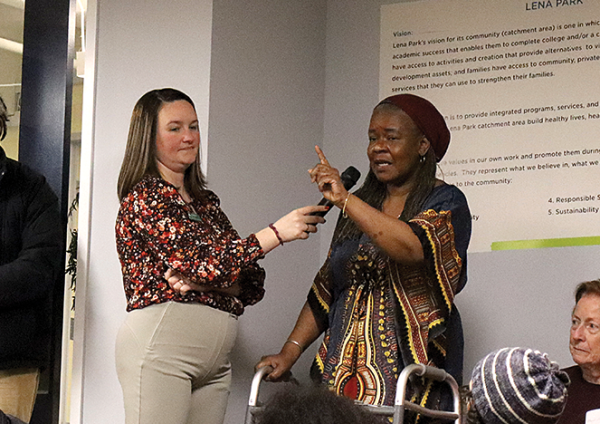

Former State Sen. Dianne Wilkerson, right, spoke during a public meeting organized by the Franklin Park Defenders at Lena Park Community Center last Thursday (Feb. 13). Karyna Cheung photo

Residents of neighborhoods surrounding Franklin Park packed a meeting last week to denounce the city’s plan to demolish and rebuild White Stadium, a move many said will disenfranchise youths and the Black community in favor of corporate interests.

The Emerald Necklace Conservancy, a nonprofit focused on preserving Frederick Law Olmsted’s system of city parks, organized the meeting to propose an alternative to the city’s plan and provide a forum for resident concerns. Demolition began last week as trucks carried felled trees from the site. Construction is expected to be completed by December 2026.

Mayor Wu’s administration and the Boston Public Schools have partnered with BOS Nation FC, the city’s new professional women’s soccer team, to renovate the White Stadium campus. The stadium, named after Boston philanthropist George Robert White, was built in 1949 and meant to be used as a facility used for city high school and community sports. City leaders and residents have long called for its renovation.

Most of the dozens of residents who gathered last Thursday in Lena Park Community Center oppose the public-private partnership that will allow the soccer team to use the new stadium for practices and 20 games a year. Some attendees said that Wu has been unwilling to consider alternate solutions.

“If you listen to what the mayor has said, there’s no other alternative. It’s this way or no way. There’s no other design,” Roxbury native Renee Stacey Welch said in an interview with The Reporter. “As people who’ve been in the city for decades, we should have options.”

Most in attendance said they don’t believe the redevelopment is a true investment for the Black community. Welch said Boston Unity Soccer Partners, the group that owns the team, is investing in White Stadium “to make money off the backs of the Black and brown community.”

She added: “Look at the things that they’re doing to the one true green space that the Black and brown community has. We’re in these meetings, and they’re talking at us, not to us.”

Welch is a member of the Franklin Park Defenders, a group opposing the project that has more than 250 members and is supported by 14 community organizations. Last year, 15 Defenders and the Emerald Necklace Conservancy sued the city, claiming the project violates the state’s Public Land Protections Act. A trial is scheduled to begin March 18.

“We believe that this public project is not following the public land protections,” said Karen Mauney-Brodek, the Conservancy’s president. “There are special protections that are afforded to public park land.”

The Conservancy has worked with the architecture firm Landing Studio to present an alternative proposal that would renovate the stadium, install a new track and grass field, and redesign the seating. Dan Adams, a Landing Studio founder, said these designs would cost $29.8 million compared to the $100 million the city has committed to demolition and reconstruction.

The city’s plan would in the end remove 145 trees to create more space for businesses and parking. Landing Studio’s plan would protect those trees.

“[We have] more public school-aged children than any other neighborhood in the city, the highest asthma and respiratory issues. And the answer is to take away the trees,” said Dianne Wilkerson, a Roxbury resident and former state senator. “We have to call it nuts. We have to challenge them.”

Children make up over 20 percent of the population in Mattapan, Roxbury, and Dorchester, the largest proportions in the city of Boston, according to US Census data.

The city, which is expected to pay half of the project’s cost, originally committed $50 million to the project. That number has grown to close to $100 million, a city official said at a city council meeting last month. Wu has said in interviews that costs increased to accommodate community input, but Jamaica Plain resident Sarah Freeman sees the cost hike as another concession to the soccer team.

“At some point my question to the city would be, when is the price too high?” Freeman said. “How much should we have to pay and compromise to get this partnership? And is the partnership even a good idea?”

Josh Kraft, a candidate for mayor, attended the meeting and said in an interview with The Reporter that the city should pause the project to reconsider community feedback.

“It’s $100 million of public money for a project that’s going to primarily benefit a private entity,” he said. “The unequivocal, consistent response of those most impacted has been concern, and that needs to be not just listened to but heard.”

Many residents argued that the plan is not designed to support youth and that deals had been brokered in the past with similarly affluent, white partners.

Hyde Park resident Domingos DaRosa compared the White Stadium redevelopment to the Carter Playground redesign, a public-private partnership supported by Northeastern University. He claimed the space that once belonged to the community was redesigned to favor the private university’s activities, despite the benefits for youth included in the project’s language.

“Stop using our students as pawns,” he said.

A page devoted to the White Stadium project on the city’s website states that public use of it will be protected and that “90% of programmable hours will be reserved for use by BPS and the community.”

Bermina Chery, who grew up in Mattapan, called the city’s reasoning a “smokescreen,” adding, “I hear proponents for the mayor’s project saying that we should have this project and it’s because it’s for the kids,” Chery said. “This project’s not only for the kids. It’s for corporate interests.”

Wilkerson questioned whether the mayor’s administration was listening to BOS Nation over its constituents and charged that the community was deliberately left out of decision-making.

“This is a political battle not supported by fact, wisdom or reason,” she said. “Someone made a promise to someone that they could have our park.”

Dorchester resident Grace Richardson was the only speaker who spoke up in support of the city’s plan. She said the renovations would improve the neighborhood and benefit youths, praising Wu “for investing in the Black community after 66 years of neglect.”

Though Richardson and other speakers disagreed on what solutions are best for White Stadium, they agreed that things must change. DaRosa, who played football at Madison Park Technical High School and played games in White Stadium, referred to Franklin Park as the “jewel of our city” and urged attendees to continue fighting for their interests.

“If we don’t bring this to the table [...] we’re just wasting our time because they’re going to do exactly what they want to do,” he said. “Their agenda is not our agenda.”

This story is the product of a partnership between The Dorchester Reporter and the Boston University Department of Journalism.