March 6, 2025

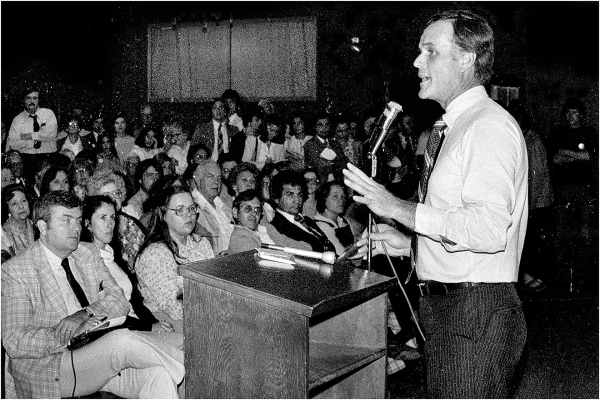

State Senator Joseph F. Timilty addressed a candidate’s forum held in 1979 at the Old Dorchester Post in Adams Corner. Timilty, a Marine Corps veteran who lived in the Lower Mills section of Dorchester, challenged incumbent Mayor Kevin White that year after coming within 7,528 votes of the incumbent White during a more competitive contest in 1975. Timilty died in 2017 at age 79. Chris Lovett photo

On Sept. 8, 1975, as many as 10,000 people showed up on City Hall Plaza to oppose a plan for expanding desegregation of the Boston Public Schools (BPS). Coinciding with the run-up to city elections, Boston’s largest political gathering in that turbulent year was not for a candidate, but for a protest.

Two months later, voters came close to breaking with a pattern in city politics that had held since 1951. They re-elected the incumbent mayor, Kevin H. White, over co-finalist state Sen. Joseph F. Timilty, but the margin was only 7,528 votes, less than 5 percentage points. That was slightly smaller than the spread in 1955 between another second-term mayor, John B. Hynes, and state Sen. John E. Powers.

In the run-up to this year’s upcoming vote for mayor, a look back at 1975 shows a very different city and a very different climate, with more sharp divisions, including a violent racial clash four weeks before the rally, at Carson Beach in South Boston. If the divisions over school desegregation were less explosive than they had been one year prior, 1975 was a difficult time for many US cities that were struggling with flight to the suburbs and the loss of manufacturing jobs. Making that worse were double-digit inflation and unemployment figures at more than 8 percent. In New York City, a fiscal crisis had prompted the creation of an outside financial control board approaching the powers of receivership.

Another source of stress for Boston, starting in the 1950s, was the displacement of thousands of households, mainly by urban renewal, together with land clearances for highway projects and expansion at Logan Airport. Between 1950 and 1980, Roxbury alone lost almost one-third of its total housing units.

One attempted remedy for displacement, through White’s “Infill Housing” program, was stymied by neighborhood opposition and the bankruptcy of the program’s lead developer. The Boston Banks Urban Renewal Group (BBURG) program, started under White in 1968 to overcome discrimination, confined mortgages for Black homebuyers to parts of Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan. That resulted in property turnover accelerated by speculative blockbusting, often followed by defaults and housing abandonment.

In 1975, the outside power looming over Boston’s elected government was W. Arthur Garrity, the federal judge who had issued the desegregation order. After rejecting a less ambitious “Phase II” plan that was proposed by a group of court-appointed masters, Garrity adopted a plan devised by two experts. Though strongly supported by the Boston NAACP, the Phase II plan met with objections from several white elected officials, including White and Timilty. But the two rivals also stopped short of expressing sharply defined policy differences over desegregation. Though both called for a peaceful reopening of school, White had the incumbent’s advantage of sending the message with free TV airtime during a moratorium on campaigning.

White had won his first term in 1967 with a runoff victory, by six-and-a-half points, over Boston’s leading opponent of desegregation, School Committee member Louise Day Hicks. In a 1971 rematch, after Timilty had been eliminated in the preliminary election, White defeated Hicks by a margin of 23.3 percent. Hicks was not a candidate for mayor in 1975, but she was on the ballot, running for a seat on the all-at-large City Council.

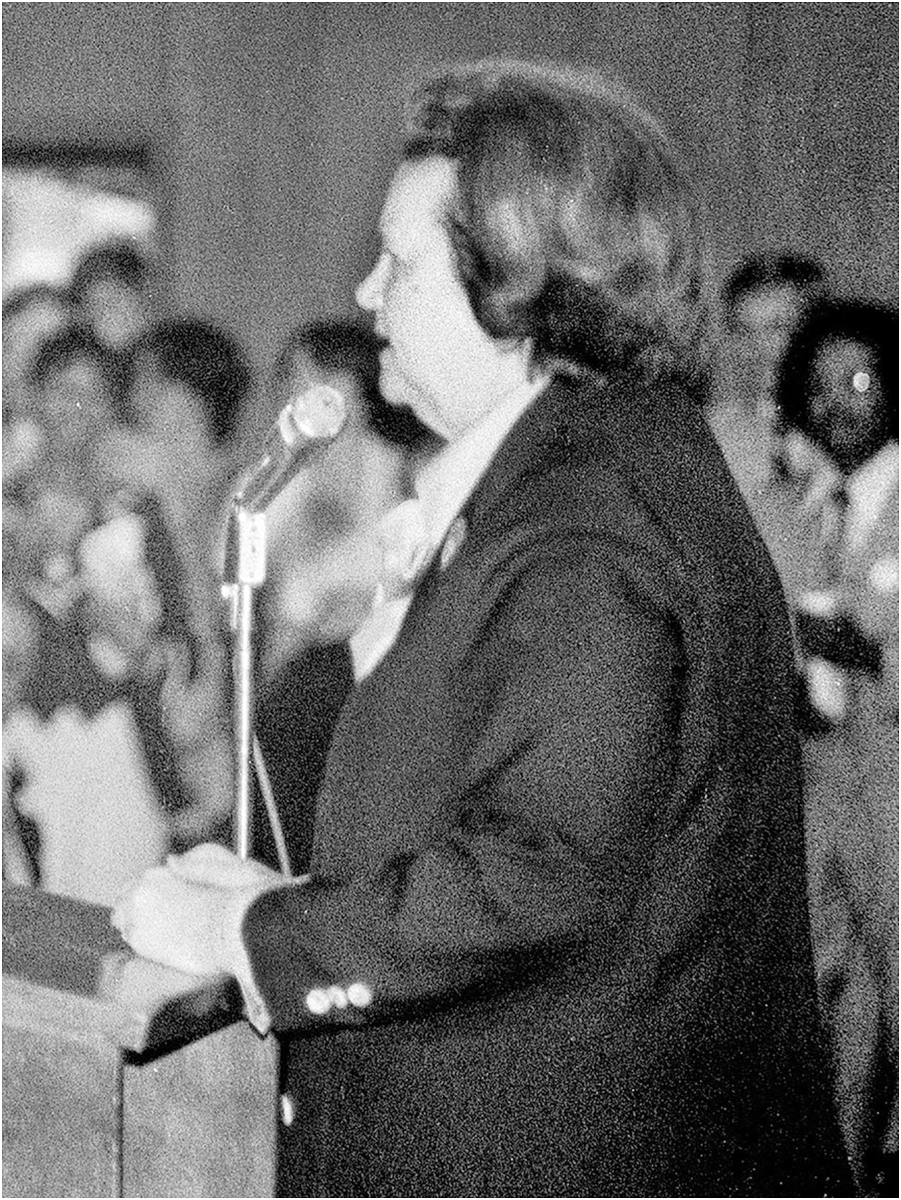

Louise Day Hicks spoke during a Dorchester forum in 1979 when she was a candidate for re-election to the Boston City Council. Hicks, who served for one term in Congress from 1971-1973, also challenged Mayor White — unsuccessfully— in 1971. She died in 2003 at age 87. Chris Lovett photo

Most of the areas carried by Hicks in her campaigns for mayor were carried in 1975 by Timilty, including South Boston, Charlestown, Ward 18 (Hyde Park and adjacent areas), and Dorchester’s Wards 13 (Uphams Corner-Columbia-Savin Hill), 15 (Meetinghouse Hill/Fields Corer) and 16 (Neponset/Ashmont). One exception was Ward 20 (West Roxbury and part of Roslindale), which flipped for Timilty. Ward 14 (Grove Hall, Franklin Field, Wellington Hill), carried by White in 1967 with 76 percent of the vote, was carried in 1975 by Timilty, but with fewer than half the combined number of votes, a result of an accelerated exodus of its Jewish population.

A 37-year-old Marine Corps veteran who grew up in Dorchester Lower Mills, Timilty was the grandson of a state senator. He was also the nephew of a police commissioner appointed by James Michael Curley, a colorful political figure who was also the city’s last incumbent mayor to lose a bid for re-election, in 1949. In 1972, after two terms on the City Council and his first run for mayor, Timilty won a seat in the state Senate, where his aides included a future Boston mayor from Hyde Park, Tom Menino.

The son of one former Boston city councillor and son-in-law of another, in 1960, White became, at age 31, the youngest person in the state to be elected Secretary of the Commonwealth. Before seeking his third term as mayor, he had run unsuccessfully for governor in 1970 and suffered another setback in 1972, when a chance for him to become the Democratic nominee for vice president with presidential nominee George McGovern was quashed by US Sen. Ted Kennedy.

Despite similarities in family background, the two candidates inhabited two different Boston worlds: Timilty, in a diverse outlying neighborhood in Mattapan, with his children in the BPS; and White, in a more patrician setting at the foot of Beacon Hill. But that difference also overlapped with a common trait of style, personified by the dashing figure of John V. Lindsay, the “Silk Stocking District” congressman who was mayor of New York City from 1966 through 1973. Noted for appearing in shirtsleeves with a jacket slung over his shoulder, Lindsay looked less like a politician than an advertising visionary on “Mad Men.”

Lindsay was a new prototype, tailored for the cooler and more casual medium of television. On the heels of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “Great Society” programs, Lindsay expanded New York’s safety net, but he also increased taxes and struggled with delivery of basic services. By 1975, with New York and Boston in crisis, the Lindsay look had lost some of its luster, even when sported locally by an underdog mayoral challenger who grew up in Dorchester.

“Timilty was not an ‘ethnic,’” recalled Ed Forry, the co-founder of the Dorchester Reporter. “He was an Irish kid, an Irish Catholic from St. Gregory’s. But he was sort of a ‘John Lindsay’ type, so he didn’t have a strong base of support from the white ethnics.”

Another political figure who grew up in St. Gregory’s Parish, Larry DiCara, made his own mark as the youngest person elected to the City Council, at age 22, in 1971. Four years later, the graduate of Boston Latin and Harvard, a political moderate with diverse support around the city, was losing ground in Dorchester and bracing himself for possible defeat, according to his memoir, “Turmoil and Transition in Boston.”

He wrote: “It was simply the worst year in politics in city history in my lifetime. The sense of betrayal and impotence churned in a cauldron that poured a poisonous potion into the very atmosphere. The evidence of political problems for me was everywhere.”

By the time the campaigning was underway, Ira Jackson, White’s chief of staff from 1972 to 1975, had left the administration. As Jackson related in a recent email, this was after he had been “totally traumatized and burned out by busing. As I recall, it was one hell of an election,” Jackson wrote, summing up the competition as a “great race and a tough slugfest” with a “formidable opponent.”

In October of 1975, many in Boston were captivated by another slugfest, the seven-game World Series match-up between the Red Sox and the Cincinnati Reds. Euphoria peaked when the Sox made their comeback in Game 6, clinched with a 12th-inning walk-off home run over the left field wall by Carlton Fisk. By the time the home team went down in Game 7, there were less than two weeks to go before the final election. And, when the contest for mayor regained the attention of voters, the news coverage was less focused on desegregation, housing, or taxes than charges of corruption.

The corruption topic was in the air as early as April, when The Boston Globe’s Spotlight Team revealed that Boston firefighters said they were being pressured to contribute to White’s campaign. Four months later, White’s fire commissioner and a deputy chief were under grand jury indictments for illegal fund raising. They were acquitted of the fund-raising charges—eight months after the election.

In the last weeks before the election, White faced new reporting alleging improper fund-raising, but Timilty was also tarnished, thanks to an assist from Boston’s police commissioner, Robert DiGrazia, then at the height of his popularity as a reformer. Five days before the election, in a volley of interviews with news outlets, he tied White’s challenger to disgruntled police officers, while linking some of the reports about the incumbent’s alleged corruption to feeds by organized crime figures.

In the end, a polarized electorate rendered a mixed verdict. White won a third term, but with his double-digit advantage in the preliminary round shaved by half. Hicks was the top vote-getter for City Council, with John Kerrigan, her former anti-busing ally from the School Committee, finishing seventh. DiCara came in fifth, 4,654 votes behind the body’s most combative conservative, Albert L. “Dapper” O’Neil.

In the voting for School Committee, Elvira “Pixie” Palladino, an anti-busing activist from East Boston, won her first term, finishing behind a more moderate first-timer, David Finnegan. Leading the pack was another moderate, Kathleen Sullivan.

According to The Globe, White’s campaign strategist John Marttila blamed the shrinking margin between election rounds on the corruption stories, as well as an incumbent’s disadvantage of being the messenger on desegregation enforcement. In “Boston Against Busing,” the historian Ronald P. Formisano cited a national factor: the “mood of disillusionment” and “an across-the-board decline in trust of public institutions,” intensified by President Nixon’s resignation in disgrace the previous year and, in April of 1975, the humiliating US withdrawal from Saigon.

Though all fifteen winners in the election were white, the margin of victory in the mayor’s race was almost exactly the same as White’s advantage with the city’s Black voters. Some of the credit for the difference was given to White’s hiring of Black men and women to high-level positions, including Paul Parks, Clarence “Jeep” Jones, and Alfreda Harris—in addition to patronage hires from various constituencies. As one activist recalled, “Kevin was an operator. He was good. He was smooth.”

In his book “Chain of Change,” the former state representative Mel King highlighted one more political factor: the organizing that took place in 1971 to support the mayoral candidacy of Thomas I. Atkins, the first Black member of the City Council since its conversion to an at-large body in 1951. In 1977, Boston voters, including an organized base in the Black community, elected John D. O’Bryant, the first Black to serve on the School Committee since 1901.

In 1979, King made his own first bid for mayor. Though he failed to get past the preliminary round, White supported an ordinance championed by King that would set hiring goals for “minorities,” women, and city residents on publicly funded construction projects in Boston. In that year’s final election, Timilty made his third try for mayor, but fell short of his 1975 total by more than 12 percent—more than three times the drop for White.

The 1975 election victories for Hicks and Kerrigan turned out to be their last, with their pool of support drained by the accelerated exodus from the city after the start of desegregation. Between 1970 and 1980, the city’s population declined by 12.2 percent, surpassing New York City’s 10.4 percent drop over the same period. Court intervention in the BPS was followed by interventions for other problems—such as public housing deterioration and harbor pollution—that elected officials failed to solve. Likewise, political engagement in Boston evolved further beyond the confines of electoral politics into community action, nonprofit development and services, and advocacy.

Looking back on 1975, DiCara and Forry see a time with more violence, more random crime, and more abandoned houses going up in flames. DiCara also recalled more job opportunities for people getting involved in political campaigns.

“Back then, people worked in the campaign because they wanted a job,” he said on reflection. “That’s really not the case as much anymore. Government jobs were good jobs. Government jobs provided stability. Government jobs provided opportunities in some cases to make some money on the side. Think of building inspectors. A lot of them got in trouble in those days. Very few people are out there today looking for a job with the city.”

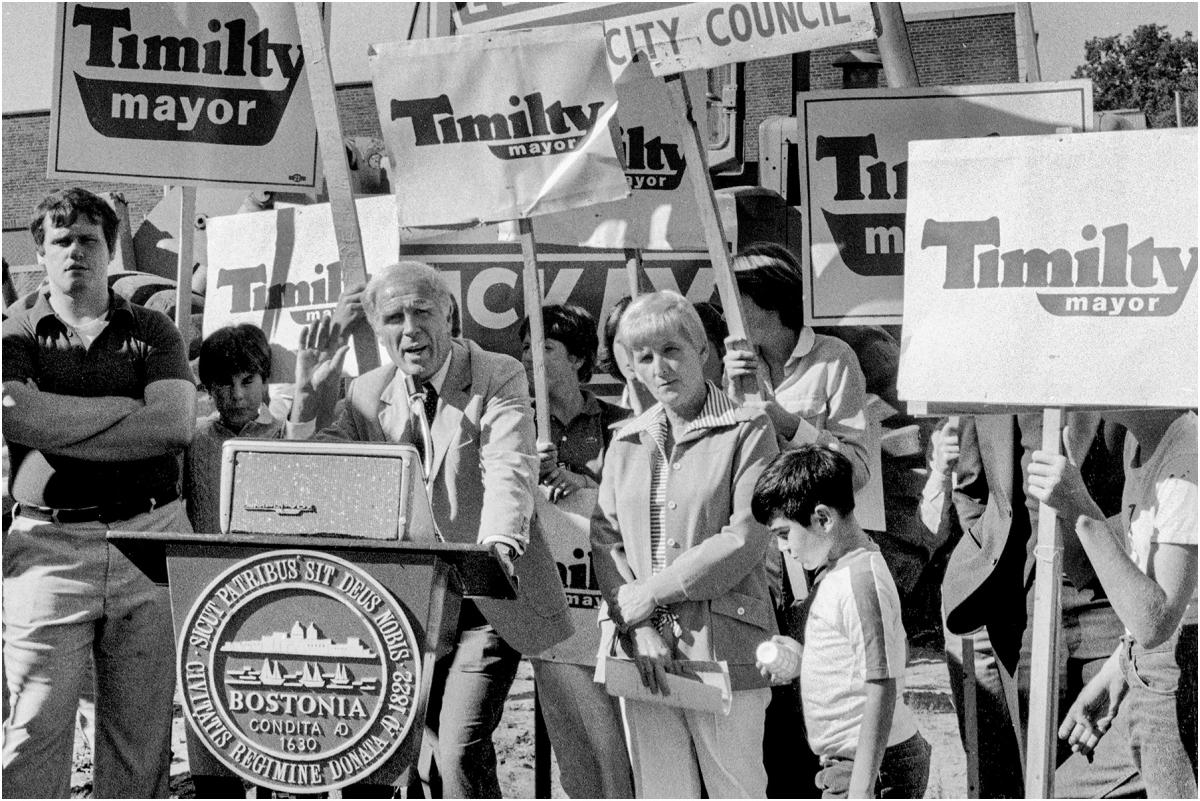

Above, Mayor Kevin White is shown at the podium during a 1979 event to announce the redevelopment of the Baker Chocolate Factory complex in Lower Mills. The incumbent was surrounded by supporters of Joe Timilty, a state lawmaker who challenged White in mayoral races in 1975 and 1979. Chris Lovett photo

Campaigns in 2025 can still highlight problems, from rising taxes on residential property owners to concerns over drug use and homelessness in parts of the city. The Boston Public Schools struggle with academic performance, but without the seismic disruptions of fifty years earlier. If too much housing in 2025 is too unaffordable, and some new housing meets with opposition from neighborhood groups, the problems fifty years ago in much of the city were plummeting property values, fallout from BBURG and Infill housing, and, especially in Dorchester and Mattapan, tax assessments that failed to keep pace with the real estate market.

When Forry talks politics with fellow members of the “Boomer” generation, the most controversial topic that comes up would have been unthinkable in 1975. “They’re all left-leaning Democrats,” he said, “and their big issue is bike lanes down Boylston street. It drives them absolutely bonkers. And they hold the incumbent mayor accountable for that.”

In elections over the past two years in major US cities, two first-term mayors made national news for being voted out. Lori Lightfoot failed to reach the final election in Chicago after the city suffered, during her administration, its highest number of homicides in more than 25 years—quite unlike the sharp drop in Boston’s homicides since 2022. In San Francisco, where incumbent London Breed was voted out last November, the main issue was the concentration of homelessness, drug use, and crime in downtown areas. Similar problems have made news in downtown Boston, where the police district, Area A1, posted an increase in non-domestic aggravated assaults in 2024—though still below the district’s total for 2019, when there were also more robberies and attempted robberies.

Unlike Boston’s mayors of at least the past century, Breed’s successor, Daniel Lurie, never previously held public office. A philanthropist and heir to the Levi Strauss fortune, Lurie cast himself as the outsider running against city hall “insiders.” Likewise, Wu’s most visible challenger so far, Josh Kraft, is also a philanthropist, along with being the chair of the board for the Urban League of Eastern Massachusetts and a son of New England Patriots owner Bob Kraft.

A four-term city councillor when she was elected mayor in 2021, Wu made her mark by her detailed policy work, especially on development regulation, climate change measures, and transportation. Unlike White and Timilty, Wu was a high school valedictorian – and a Harvard University and Law School grad who, as a first-generation political candidate, became the first woman and person of color elected mayor of Boston.

If Wu and Kraft differ from their Boston predecessors, DiCara expects little change from the pattern with the city’s incumbent mayors. By his reckoning, almost any challenger in the final election could get one-third of the vote, while a “strong challenger” could get about forty percent. “And the question is,” he wondered, “where do they get the other ten percent? And, looking at the map, and I know the city precinct by precinct, I don’t see where Josh gets the votes.”