March 26, 2025

The latest nonsense emanating from Pennsylvania Avenue about annexing Canada as “the 51st state” reminded me of a story that appeared on the cover of this newspaper in 1999— some 26 years ago. The narrative detailed the recent discovery of a shipwreck in the St. Lawrence River near Quebec City, the fortress-like city that was a coveted prize back in the days before the United States of America or Canada existed as countries.

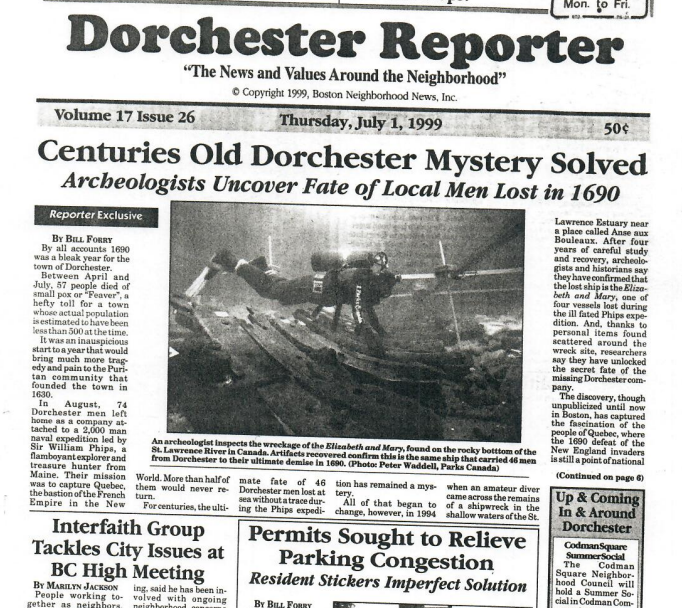

The ship that was unearthed from the rocky bottom of the river, it turned out, was the remnants of the “Elizabeth and Mary,” one of a small flotilla of some 30 boats that carried soldiers from New England as part of an “expeditionary force” deployed in 1690 by the English in an attempt to seize Quebec City from the French.

The 2,000-man force included 74 men from Dorchester, of which 46 never returned to the shores of the Neponset or Savin Hill.

The “Phips Expedition” was named for its leader Sir William Phips, a mariner and shipbuilder who was the first colonist to be “knighted” by the crown back in London. In the summer of 1690, Phips and his militiamen made an arduous journey north and finally reached Quebec City in October, several weeks later than expected. By then, supplies were scarce and the weather had taken a cold turn.

“This was the largest military effort ever mounted by an English colony up to this time,” Emerson Baker, a professor of history at Salem State College, and author of a biography of Phips, told me in 1999. “This was an all-out effort by Massachusetts. It was an incredibly expensive venture.”

The Phips party demanded Quebec’s surrender, but received instead cannon fire from the commanding heights. With casualties mounting, Phips wisely ordered a retreat. Four of the craft — including the “Elizabeth and Mary,” which carried the majority of the Dorchester volunteers – went missing in a storm.

The 46 Dorchester men— fathers, brothers, sons— were gradually given up for dead, even as Phips himself made it back safely and was named “governor” of Massachusetts for his troubles.

The first traces of the sunken vessel and personal items from our long-lost neighbors were at long last located in 1994, when a sport diver spotted something unusual in about 15 feet of water. After several years of artifact recovery— ammunition, personal effects, wine bottles, muskets— the Canadian government announced that the wreck was indeed the last refuge for most of the ill-fated Dorchester company.

Two items were tied to Cornelius Tileston and Increase Moseley, two men who had sailed north with the Dorchester company, but had never returned.

One survivor of the sinking eventually did make it back to his native Roxbury, but not before first being captured by native people and sold into slavery.

The wreck’s discovery and connection to the Phips expedition prompted a lot of buzz in Quebec, where the 1690 victory over the New Englanders is still a source of pride. The French were eventually dislodged in a different colonial-era conflict and by 1763, the British controlled what we now know as Canada, which was a battleground again with Americans during the War of 1812.

The new occupant of the White House seems to have new designs on our neighbors to the north and for a long time one of our closest allies. Perhaps his advisors— and all of us— might do well to consider the cost paid by Sir Phips’ men in the long-ago autumn of 1690.