January 8, 2025

Jeff Calish spent his early years in Dorchester’s once-large Jewish community. Here, he stands in front of what was the Russian Shul, Agudas Israel Anshe Sfard, on Woodrow Avenue. Across the street, was the former Congregation Hadrath Israel building once known as the Lithuanian Shul. It is now the Friendly Church of Christ. Seth Daniel photos

Some of them are hidden behind beige vinyl siding and others stand alongside modern church signage across parts of Dorchester and Mattapan – a Star of David, assorted Hebrew characters, cornerstone markers with dates in the 5,000s drawn from the Jewish calendar. They are the remnants of a time not so long ago when synagogues marked the substantial presence of the Jewish community in these and other neighborhoods of Boston.

What life was like in those times is familiar to 75-year-old Jeff Calish, who grew up in Dorchester in the 1950s before his family relocated to Randolph. He resettled here in 1986 and recently began leading tours and giving lectures across the city on the history of the Jewish community in Roxbury, Dorchester, and Mattapan.

Last November, Mass-Pocha, the journal of the Jewish Genealogical Society of Greater Boston, published his history, “The Synagogues of Roxbury, Dorchester, & Mattapan.” With the help of the Dorchester Historical Society (DHS), he presented his first lecture over a year ago. He also presented more recently to the UMass Boston OLLI senior group, and at the Mattapan and Parker Hill branch libraries.

“I try to make it more than just the synagogues,” said Calish. “The buildings are a big part of it, but it’s about the people, too, those that were inside the buildings and came from those buildings.”

Calish grew up on Strathcona Road in Four Corners and attended the Christopher Gibson School. But after a few unfortunate incidents targeting his brother, he said, the family moved to Grove Hall’s Hartwell Street and attended the large Mishkan Tifila Synagogue on Seaver Street. His father operated a jewelry store on Tremont Street downtown.

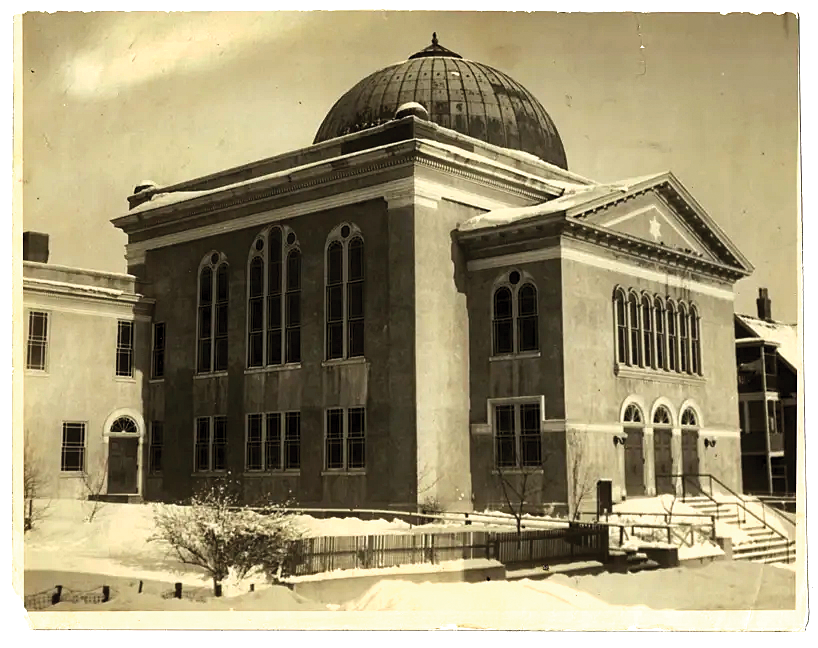

Temple Beth El was a striking building located along Fowler Avenue just south of Franklin Park. The congregation left in the 1960s, and the building was demolished in 1997. The site is now a vacant lot. Photo courtesy DHS.

As more and more Jewish families left the city in the late 1960s during a period marred by a deliberate strategy by lenders and political leaders to “redline” Boston’s neighborhoods along ethnic and racial lines, the Calish family moved to Randolph, where Jeff attended high school and later studied information technology in college before he and his wife returned to Dorchester’s Ashmont Hill, where they raised two daughters.

His daily travels from there often brought him in contact with the places he knew well from his childhood days. Many of the modern-day Black congregations that now own former synagogue buildings have kept the exteriors largely intact – with markers that identify them as Jewish houses of worship.

Calish was always curious about the wider history of Jews in Boston, and it was the onset of the pandemic that afforded him the opportunity to dig deeper. “When it hit, I needed something to do and I started researching,” he said. “I was just fascinated with all the information.”

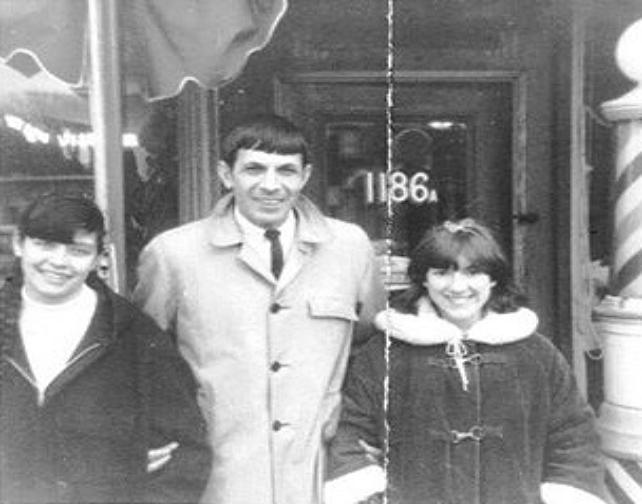

Leonard Nimoy, Star Trek’s “Spock,” with his sisters pictured in front of their family’s barbershop at 1186 Blue Hill Ave. in Mattapan. The address is now home to Hair It Is Barbers. Photo courtesy Jeff Calish

Some of the prominent Jewish Bostonians he highlights include Leonard Nimoy, famous for his role as ‘Spock’ on Star Trek. The Nimoy family operated a barber shop at the corner of Morton Street and Blue Hill Avenue. The actor was fascinated, Calish said, by some of the ceremonies and rituals in the Jewish temples and took the “live long and prosper” sign directly from Jewish ceremonies. The famous composer and director Leonard Bernstein and the journalist Theodore White were other well-known Jewish men with roots in Boston’s neighborhoods.

In his history, Calish traces the Jewish settlement in Boston to the 1800s and notes that the population was very small compared to cities like St. Louis, Cleveland, Philadelphia, and Louisville.

The first synagogues were located in the North End and South End in the early 1800s, yet the overall population was only 1,000 in the 1860s at the time of the Civil War. But in the later decades, as Jewish populations in eastern and central Europe faced persecution, more Jewish individuals and families moved to Boston – and eventually, Dorchester, then Mattapan.

This influx built synagogues and other cultural institutions all over the area, with 22 logged in Dorchester and 6 in Mattapan and another 30 in Roxbury, mostly on the Dorchester line in Grove Hall. By 1950, he says, the Jewish population in Dorchester, Roxbury and Mattapan was put at about 70,000.

Much of the synagogue history was lost, he points out, because the Jewish population left so quickly, but also because congregants were not allowed to take pictures or write notes on the Sabbath.

“People had no cameras, did not take notes or record their history or the things that happened, and so there isn’t much history about them,” he said. “When they had services, there were no notes taken because they couldn’t. For conservative and orthodox congregations, on the Sabbath one major rule is you cannot use energy to create anything.”

Restrictions like that played into a theme of synagogue expansion. Many congregations would build large buildings and attract large populations, but because observant Jews weren’t allowed to drive cars on the Sabbath, they requested smaller ‘shuls’ near their homes so they wouldn’t have to walk so far.

Congregations that met first in a rabbi’s home grew larger— and required additions, which is why many former synagogues were in what appear to be homes. A common addition was a separate entrance for women, which kept the them out of the rabbi’s home and separated from men during services.

This feature is prominently observed at the current St. Luke’s AME Zion Church at 1099 Blue Hill Ave., which once housed the Young Israel of Mattapan congregation.

Some synagogues were formed around native countries – Russia, Lithuania, Ukraine, Poland et al. – while others formed around ethnicities – Sephardic (Spanish) Jews, or Ashkenazi (European) Jews.

This was prominent in the clusters of congregations on Lawrence Avenue and Intervale Street in Dorchester, as well as on Woodrow Avenue near the Mattapan-Dorchester line.

The former Congregation Hadrath Israel building, once known as the Lithuanian Shul, is now the Friendly Church of Christ. Seth Daniel photo

Congregation Hadrath Israel (now the Faithful Church of Christ) was known as the Lithuanian Shul, while across the street, the Agudas Israel Anshe Sfard (now Temple Salem Seventh Day Adventist) was known as the Russian Shul.

“I was most surprised about all of the activity on Woodrow Avenue,” said Calish.

There were also simple disagreements, he said, which was on display at Woodrow Avenue when the Beth Aknosis Paoli Anshe Sephardic formed as a breakaway from the Russian Shul.

“From my research, a lot of the synagogues were formed because people were upset over a new rabbi or who became the cantor or something else like that,” he said. “You aren’t tied to any congregation, and you can do what you want. It’s not like the Catholic Church where you’re in a geographic parish.”

Calish points out that one of the oldest congregations in the region set itself up on Dakota Street, in what is now a Haitian evangelical church. The one-story building housed Mishkan Israel, a conservative synagogue founded in 1858 by Polish immigrants. It was first on Westville Street, then moved to 480 Geneva Ave. In 1930, they opened the building at 137 Dakota St.

The congregation dissolved in 1977 but the synagogue building is the oldest of those still standing in the Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan area.

A non-religious structure – but very important to the Jewish population of that time – was the rock wall at Franklin Field along Blue Hill Avenue. During the high holidays of Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur, it was the spot to be.

“On the high holidays, services would go on continuously, but there was a break, and a lot of people gathered on the wall at Franklin Field,” he said. “Young groups from all over, every congregation, in jackets and ties – hundreds of us – would be there hanging out.”

Of course, there are hundreds of other such historical notes, and Calish said he would like to share all he’s learned by staging more presentations and lectures across the community.

“I think it’s part of the history of the community and the large Jewish community is gone,” he said. “A lot of young people don’t know much about it and a lot of people who are older see my presentation and remember going to these places – recalling they had their bar mitzvah or other big moments at some of these buildings.”

Calish can be reached for questions or to request his presentation at jcalish@hotmail.com.

For more in-depth studies about this subject, visit the Jewish Geneaological Society of Greater Boston at jgsgb.org.