June 20, 2024

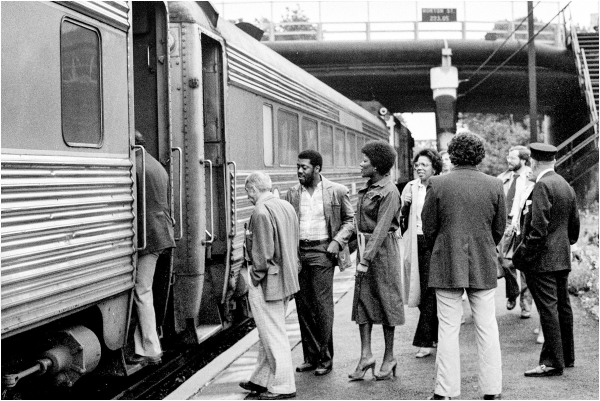

Passengers moved onto a Fairmount line train in 1980 for a ride organized by local advocates to promote use of the service. Man with back turned is the late Pat Cooke, a prominent advocate of the line. Chris Lovett photo

Thanks to a June 11 vote by the MBTA’s board of directors, the Fairmount commuter rail line is moving closer to a long-pursued goal of cleaner and more frequent service.

In the $9.6 billion capital investment plan for 2025-29 approved by the board, the MBTA commits to funding a pilot program for electric trains to replace the current fleet, which is powered by more environmentally harmful diesel fuel. The plan calls for facility improvements, along with upgrades of track, signal, and power infrastructure to operate the “decarbonized” trains every 20 minutes.

A “frequent user” of the line, state Rep. Brandy Fluker Oakley, hailed the pilot program as a response to transportation needs in her district (parts of Dorchester, Mattapan, and Milton) and public health concerns. She cited elevated higher rates of asthma in Mattapan detected by the Boston Public Health Commission, as well as the history of longer commutes between the neighborhoods and downtown Boston.

At a meeting three weeks before the vote, the board heard support for the pilot from the co-chairs of the Fairmount Indigo Transit Coalition, Pamela Bush and Marilyn Forman.

“This commitment to electrify the line is a monumental step forward for the communities along the corridor, and we are eager to see these plans come to fruition sooner rather than later,” Bush told the board.

“It’s not only an environmental imperative to electrify now, but also a smart move for combating climate change,” she said. “By encouraging more public transit use, we can reduce the overall carbon footprint and contribute to a healthier planet. We have very high asthma rates along the Fairmont line, and it is not getting better. It is getting worse. And we have seen manifested health impacts of the diesel polluting trains that run up and down the line.”

Bush and Forman got an immediate show of support from Mary Skelton Roberts, the board’s Boston representative who was appointed by Mayor Wu. “The Fairmont line does need to be a priority,” Skelton Roberts concurred. “It enables us to get people where they need to go in a way that’s efficient. It’s a climate strategy and a public health strategy.”

In 2019, the MBTA’s Fiscal Management and Control Board voted to transform the commuter rail system into “a significantly more productive, equitable and decarbonized enterprise,” starting with projects on three branches, including the Fairmount line. Before the board’s vote, the commuter rail operator, Keolis, had proposed decarbonizing the Fairmount Line as early as 2026, with trains powered by batteries known as “Battery Electric Multiple Units” (BEMU).

“Building on our priority to introduce Battery Electric Multiple Units on the Fairmount Line, the MBTA is in the final phase of selecting and recommending a contract to the board of directors,” the agency’s director of communications, Joe Pesaturo, explained after the June 11 vote.

“By transitioning to zero-emission vehicles and significantly increasing service frequency,” he added, “we’ll be taking a crucial step toward achieving the Healey-Driscoll Administration’s ambitious climate goals while addressing the need for improved transit along the Fairmount Line corridor.”

Though the MBTA’s request for proposals requires service at 20-minute intervals, details about technology, power source, and scheduling will not be finalized until a contract is awarded, pending the approval by the board of directors. While supporting the BEMU technology as part of the decarbonization, Bush argued earlier this week for including overhead electrification, despite its additional cost and time for construction. Her advice: “We’re saying keep our options open.”

In a February 2023 report, transportation advocates at A Better City (ABC) and TransitMatters expressed concerns about evolving BEMU technology, calling for more disclosure on how electrification would affect performance. “While rail electrification does deliver some decarbonization benefits on its own,” the report noted, “it is ultimately secondary to the mode shift benefits delivered by best- practice electrification. Doing so would enable the delivery of service at least every 15 minutes on key corridors.”

In response to the June 11 vote, ABC’s senior advisor on transportation, Caitlin Allen-Connelly, was clearly supportive. “The pilot is a clear and welcome signal from the MBTA and the Commonwealth of their commitment to move regional rail forward in Greater Boston,” she wrote. “Bringing service delivery improvements and environmental benefits to the Fairmount Line opens up access to better transit and addresses public health concerns in an environmental justice community. The pilot is an important first step and a recommitment to decarbonizing the commuter rail system.”

In April of this year, the MBTA increased weekday service on the Fairmount Line from once every 45 minutes to once every 30 minutes. According to Pesaturo, ridership on the line through May of 2024 has increased over the same period last year by 47 percent. The upward trend had also been noted by TransitMatters, whose executive director, Jarred Johnson, called the Fairmount line “a great place to start” with electrification because it has the character of a transit line, in contrast to other commuter lines carrying a higher percentage of riders all the way from outlying communities to South Station. And he notes that electrification would allow trains making stops to accelerate more quickly.

“It’s already a line that’s being used for folks to go to the grocery store, doctor’s office visits, for kids to go to school,” he said. “It’s a really perfect place to demonstrate how increased frequency can drive additional ridership.”

The Fairmount rail corridor was revived for passenger service in November 1979, after its tracks were refurbished to carry the rail traffic that was temporarily displaced by work for relocation of the Orange Line along the Southwest Corridor.

Platforms for passenger stops were built near Morton Street and Uphams Corner, but the local service was limited. Even at that time, local advocates were calling for more frequent service and fares that would be more competitive with other options on the MBTA.

One year after the start of service, the MBTA found itself in the center of a budget showdown prompted by the adoption of “Proposition 2 ½,” which imposed new limits on property taxes levied by cities and towns. Before state legislators could reach a budget compromise to ease the MBTA assessment for local communities, service was shut down for a whole day.

At the May 23 meeting, MBTA officials and board members were still contending with budget pressures. Thomas M. McGee, a board member and former mayor of Lynn, said the capital investment plan was still far short of what was needed for service and climate goals, and that support had to be mobilized beyond the Legislature. “And that can’t be minimized,” he warned, “because if we don’t, we have choices to either do something or to continue on a road that creates constant gridlock, lack of housing, and inability grow our economy.”

The earliest community advocates for local stops on the Fairmount Corridor also had an eye on how the service could affect housing supply, at least as a remedy for disinvestment marked by abandoned buildings and a loss of units. After scattered housing construction on vacant land by non-profit developers, the rail line would become a magnet for larger “transit-oriented” projects, all the way from its southern terminus in Readville to the Newmarket stop near the South Bay Mall.

Thirty years ago, policy experts questioned the efficiency of commuter rail throughout the Boston region for switching commuters from motor vehicles to public transportation. Thirty years later, Jarred Johnson points to Allston Landing as a prime example of how investment in transit can spur new development to ease the housing crunch—along with more travel less dependent on fossil fuel.

“I think it allows us to build denser and, therefore, cheaper housing,” he said. “It allows us to build housing with less parking, which is also cheaper and allows us to pass those savings on to the people who are renting or buying the home. It absolutely does it – it opens up new areas for housing production, both affordable housing and market-based housing, that the region really, really needs.”

Though Forman of the Indigo Transit Coalition grants that transit service along the Fairmount Corridor is still “a work in progress,” she says that better transit and new development can also make neighborhoods along the route more “walkable,” with more destinations at close range and less dependence on cars.

“If we get those things in and around our neighborhood, there’s no reason for us to go to someone else’s neighborhood or feel like we have to drive somewhere to get what we need,” she reasoned. “Everything should be walkable, everything should be convenient, and that includes transportation.”

Forman grew up within two blocks of what is now the Fairmount line’s Four Corners-Geneva Station and still lives in the home where she was raised. Decades before the station was built, the neighborhood had vacant lots that were used for dumping or mined for reusable bricks from demolished buildings.

She also remembers when children in the neighborhood were playing basketball and taking shots at a milk crate attached to a pole. Wanting something better and acting on advice from neighborhood teens, she became a community advocate at age 11, gathering signatures for a real basketball court at Fenelon and Merrill streets. To bring the petition to Kevin White, Boston’s mayor at the time, Forman needed a trip to the elevated Orange Line, so that she could ride into downtown. White responded by coming to the neighborhood and putting up a sign promising a new court, which opened a year later.

In 2023, the same playground was picked as winner of Red Bull’s “Get in the Paint” contest for basketball court renovation. That resulted in a visit by another well-known figure, Boston Celtics forward – and future NBA Finals MVP –Jaylen Brown. It was one more opportunity to boast about the power of community action.

“So I was right there in the middle telling that story, just how community really, really can make change,” said Forman. “I mean, I’m proof. You know, it can happen if you get involved in your community. Whatever you want to happen can happen, as long as it’s not self-centered and it benefits the masses of people.”