August 12, 2024

A group of nurses from Carney Hospital and the Mass Nurses Association gathered outside the offices of Boston city councillors last Wed., Aug. 7. The council later voted 12-0 to approve a resolution calling for a public health emergency in Boston based on the anticipated closure of Carney Hospital later this month. Chris Lovett photo

For a few minutes on Aug. 7, the entrance to the offices of Boston’s city councillors looked like a scene at a hospital.

Lining up at the reception desk were about a dozen people seeking a kind of late-stage emergency response. They were nurses, some dressed in scrubs, who wanted to keep the Carney Hospital in Dorchester open beyond the expected closing date of August 31—a goal that would be officially endorsed the same day in a council resolution.

If the resolution was cheered as hope for a remedy, it could also have been downgraded to a palliative. Even before the meeting, as city and state officials scrambled to make new arrangements for the Carney’s patients, nurses knew the vital signs of its operation were trending downward.

Elaine Graves, a recovery nurse who has worked at the Carney for 48 years, recalled that when Steward Health Care became its owner, in 2010, the intensive care unit had 16 beds.

“Right now,” she updated, “it’s a four-bed ICU, because of staffing.”

According to figures compiled by the Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association (MHA), patient volume at the Carney had declined by 41 percent from January to June of 2024, with a drop of 30 percent at another Steward facility, St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center in Brighton. Last year, Carney’s emergency department had about 30,000 visits. In June of this year, the month after Steward’s filing for bankruptcy, the MHA reported that the average inpatient census at the Carney was down to 13, out of 83 medical beds.

The day before the hearing, it was reported that the Carney Hospital property, sold by Steward to a real estate trust in 2016, was now controlled by the asset management firm Apollo Global Management. Though Graves insisted that the hospital was still in operation, she detected an absence that extended beyond patients.

“There’s not any management in the building,” she said, “that has a clue as to what’s going on.”

In response to plans by Steward to close the Carney and its Nashoba Valley Medical Center in Ayer, Massachusetts, the MHA’s president & CEO, Steve Walsh, issued a statement last Friday, striking a note of reassurance.

“Community members and healthcare professionals should know that MHA and our member hospitals have their backs,” Walsh stated. “For the past eight months, we have been working daily with the state to prepare for any scenario that comes our way – including any closures. Although this is a challenging time for our healthcare system, our member hospitals stand ready and prepared to meet the needs of every patient.”

As she waited in the hall outside the City Council Chamber, Graves recalled the scenario almost ten years ago, with an increase in emergency patients at the Carney after the closing of another Steward acquisition, Quincy Medical Center. She and her colleagues were now expecting another migration of patients.

“We ask where they’re going to go, now that the Carney is closing,” she said. “They’re all going to Boston Medical Center.”

The day after the City Council meeting, the executive director of the Boston Public Health Commission, Dr. Bisola Ojikutu, said that Mayor Wu’s administration was “focused on the immediate term,” trying to head off lapses in emergency, urgent, and behavioral health care that had been provided by the Carney. Among the efforts she mentioned were twice-weekly meetings with the Conference of Boston Teaching Hospitals, including ways to make up for the loss of the Carney’s screening programs.

“It's August 8, and it's closing on August 31st,” Dr. Ojikutu explained, “so we’re really looking at expediting understanding exactly what we're going to do and what we're going to do differently. But, no doubt, there's going to be challenges, and there are going to be issues at other healthcare centers, both inside and most likely outside of Boston.”

Even before Steward’s bankruptcy filing, there were signs of increasing strain on Massachusetts hospitals. One recent report, by the Center for Health Information and Analysis (CHIA), pointed to increasing difficulties with access to primary care, which could result in more patients going to hospital emergency rooms, in addition to people going to hospitals in Metro Boston for emergency shelter services. In CHIA’s survey, the number of people in Massachusetts reporting difficulty with access to “necessary health care” had increased between 2021 and 2023 from 33 percent to more than 41 percent.

In May, the MHA published a report on what it called the “Healthcare Crisis” that marked a declining number of staffed beds at hospitals, aggravated by delays on transitioning patients to a different level of care at other facilities. Eighty percent of the patients awaiting discharge were in Metro Boston, almost three-quarters of them seeking admission to short-term rehab. Along with occupying beds needed for active care, the MNA warned, “boarding” patients also posed a greater financial burden for hospitals.

Helping to absorb some of less acute patient needs are community health centers in Dorchester, especially with the urgent care programs offered by DotHouse Health and the Codman Square Health Center.

(Codman's Urgent Care Hours are 8 a.m. to 8:30 p.m. Monday-Friday; Saturday 9 a.m.-3 p.m. It is closed on Sunday. An earlier version of this article indicated that is open 24/7, which is not correct.)

DotHouse Health’s CEO, Michelle Nadow, said last Friday that there have been 3,000 more urgent care visits than expected for the current fiscal year. She attributed part of that to a “chilling effect” caused by reports of Steward’s bankruptcy and possible closing of hospitals.

“Some people choose not to go to those facilities, because they know they're not going to continue to be able to receive care there,” Nadow surmised. “And some of it is this kind of tightening around primary care access. So, when we see people come to our urgent care in the last year, we're seeing higher rates of acuity – it's unmanaged diabetes or hypertension, haven't had recent screenings, haven't had recent well child visits or immunizations.”

Even without a full shut-down of the Carney Hospital, according to Nadow, the urgent care program has already been pushed to its limit.

“I would say probably two or three times in the last couple weeks, we've had to close our urgent care because it's already hit volume,” she said. “That means there's already a two-hour wait, so we feel those overcrowded-ness issues as well.”

Nadow measured the loss of the Carney in capacity for emergency care and behavioral health treatment, in addition to preventative screening programs.

“What we're really concerned about is those true emergency room visits,” she said. “Where are they going to go because of the overcrowding in our emergency rooms right now? And are the places where those patients are going ready to receive them in terms of being culturally and linguistically competent?”

Nadow counted 200 DotHouse Health patients who were referred to the Carney last year. Though most patients from DotHouse Health were referred to Boston Medical Center, she noted, “for some of our patients, Carney is the provider of choice for specialty referrals, for a lot of reasons. One is proximity to where they live. They don't need to navigate a larger campus, find parking, all of that. I think also our patients feel very comfortable knowing that their language needs are going to be met when they go to Carney. There are so many bilingual, trilingual staff who speak the languages that our patients speak, predominantly Vietnamese.”

In 2023, Boston Emergency Medical Services (EMS) transported 6,313 patients to the Carney Hospital, a slight decrease from the total in 2022 and accounting for 7 percent of all its hospital trips in the city. Most of the trips to the Carney originated from Dorchester and Mattapan. The hospital is also the base for an EMS paramedic ambulance.

Last week, a spokesperson for Boston EMS said it was “deeply concerned” about the potential closing.

“It is our priority to ensure all patients continue to receive the pre-hospital care that they need,” the spokesperson said in a written statement.

“Without this hospital, patients will be transported to other Boston hospitals, some of which are already experiencing capacity issues. This is likely to result in increased transport times for patients forced to travel further to the nearest hospital as well as prolonged turnaround times for ambulances.”

The resolution approved by the City Council called for trying to save the Carney by declaring a health emergency. In the event that no bidders were to be found, the measure urged the city and state to be prepared to seize the property by eminent domain and continue services at the hospital until a take-over by a new operator.

Though Gov. Healey has called for Steward to observe a 120-day notice period before the closings, questions have been raised about the state’s ability to force hospitals in bankruptcy to continue operating. On July 31, when Steward was granted permission to close two of its hospitals by the end of the month due to the lack of “qualified” bids, Healey’s Secretary of Health and Human Services, Kate Walsh, determined that “the market has spoken.”

The very next day, Mayor Wu sent a letter notifying the hospital property owners that any new development for a use other than healthcare would meet with zoning hurdles, but Ojikutu ruled out even a temporary take-over by the city. She argued that the city was not in a position to keep the hospital in operation, or even to assume emergency powers normally invoked for a “dire” health threat.

“We don't have that authority, and a public health emergency would not give us that authority,” said Dr. Ojikutu. “In addition – I think this is the other key piece – a public health emergency is not tied to any additional funding or resources.”

Meanwhile, a city spokesperson tried to dispel conjecture that the administration was party to yet another future possibility, using the Carney campus for substance use treatment and supportive housing programs proposed for the Shattuck Hospital site in Jamaica Plain.

“We continue to partner with the state and all local stakeholders to ensure access to care,” the spokesperson said. “We have not heard of or been involved with any conversations about the relocation of the Shattuck at this site.”

After the federal bankruptcy judge in Houston allowed an expedited closing of the two hospitals, there were reports that the facilities had drawn bids that were rejected. That bolstered the call by the Massachusetts Nurses Association (MNA), in a letter last week, for using money from the state’s “rainy day fund” to keep the hospitals open until new ownership is secured.

Though the Healey Administration is pledging support for transition to new ownership at six Steward hospitals in Massachusetts, Alan Sager, a professor of Health Law, Policy, and Management and the director of the Health Reform Program at Boston University School of Public Health, argued that the state had a rationale and the resources to get the other two hospitals “back on their feet.”

He added: “The state has a capacity crisis. Many ERs are crowded, and many patients wait in hallways for beds. That will be worse this winter.”

Sager also concluded that since an interim status pending transition to some other combination of services would be unlikely to halt the migration of patients and staff, the only alternative would be closings. But he cautioned that relocating the Carney’s services to other providers would disrupt a “fabric” of ties with a community developed over time.

The was part of the case for an emergency declaration made by Boston city councillors at last Wednesday’s meeting. Two at-large members, Julia Mejia and Erin Murphy, spoke about their own experiences as Carney patients. Council President Ruthzee Louijeune, whose parents are Haitian immigrants, mentioned the connection between the hospital and the Hyde Park medical practice of Dr. Jean S. Bonnet, and that her godmother also went to the Carney for care.

“Can she go somewhere else to seek it? Yeah, but there's a comfort in going to Carney Hospital where your doctors speak your language, where you've been going for decades and decades, and where your trust in the healthcare field between patient and doctor, or between patient and nurse, is something that's really hard to come by,” Louijeune said the day after the meeting. “So, once you establish that rupturing, it is a huge loss, especially with communities where we're trying to bridge those gaps, to help close our health equity gaps.”

Also contributing to the gaps was the recent closing of four Walgreens stores, in Roxbury, Mattapan and Hyde Park.

“We cannot afford to lose yet another healthcare provider,” District 4 (Dorchester/Mattapan) Councillor Brian Worrell said before the vote on the resolution at last week’s meeting. “We've already lost Walgreens and CVSs in our neighborhood, and we must be both dedicated and creative as we work toward this plain and simple goal… to keep a hospital open in Dorchester to address the needs and the diverse and growing population.”

The original sponsors of the Carney resolution were District 2 (South Boston, South End, Chinatown) Councillor Ed Flynn and District 3 (Dorchester) Councillor John FitzGerald. While voting with 11 colleagues in support of the measure, FitzGerald acknowledged that trying to use emergency powers to save the Carney, by itself, was a long shot—though better than accepting a more irreversible shutdown.

Above, Councillor FitzGerald argues the case for keeping Carney Hospital open. Chris Lovett photo

“We understand that legally there's not a lot of options we have left, but we can still, through things like the mayor's letter, create the environment where we make it as beneficial to both sides as possible to create a deal to keep a hospital there. That's the job,” he said the day after the meeting. “We can still apply pressure. We might not have legal levers to pull, but there are other tools that we have to create an environment where a deal can be struck.”

The same day, the environment was also defined by a letter from US senators Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey to Apollo Global Management, citing its earlier financial backing of the Steward hospital properties’ previous owners. “The fate of the remaining six hospitals,” they wrote, “remains uncertain while bid negotiations continue – in large part because potential buyers had been unwilling to assume the onerous leases held by MPT and MIP (Medical Properties Trust and Macquarie Infrastructure Partners).”

The next day, there was even more uncertainty reflected in a State House News report that a bidder might also be lacking for Steward’s Holy Family Hospital campus in Haverhill.

That prompted a call by State Senator Nick Collins (D-South Boston/Dorchester) for officials to rethink the meaning of the healthcare market.

“With the news of the Holy Family deal on life support, it is time for state health officials to admit what we all know: Since the passage of health care reform in 2006, the Commonwealth is ‘the market.’ Our state health officials can’t just blame Steward anymore,” said Collins. “The state has the power and money to save and stabilize all our community hospitals. We are already in what medical professionals categorize as an acute care crisis. Allowing community hospitals to be closed amidst this crisis would deprive vulnerable residents of their access to health care, and particularly emergency care, and that is simply unsafe.”

Even before acquisition by the for-profit Steward Health Care, there had been concerns about the future of the Carney Hospital, perched between the migration of its historic Irish Catholic base to the suburbs and an influx of newer Dorchester residents, many of them medically under-served and more reliant on public funding for care. Despite efforts from community health centers and some hospital administrators to serve more of the new population, there was resistance from some of the medical staff, with the Carney later cutting back on some of the ties that had been cultivated with the health centers.

According to The Boston Globe, the level of engagement with health centers would also emerge as an issue at Carney under Steward. That was also reflected in 2016, when the Carney decided to shut down a new residency program in family medicine that supporters had touted as a way to boost service to the surrounding community.

In 2010, before the Caritas Christi hospital network acquisition by Steward and its owner, Cerberus Capital Management, was approved by former state Attorney General Martha Coakley, Sager raised concerns to her in a seven-page letter. Among his suggestions was the call for a receivership law that, as with a similar measure for nursing homes, would allow for the takeover of hospitals.

“The sale of Caritas to Cerberus is usually described as a way to keep the six hospitals open. But what if it actually has the effect of facilitating the closing of one or more of the hospitals?” Sager cautioned, later adding, “It is wrong-headed, I think, to allow for-profit firms' transient or spasmodic financial needs to determine which Massachusetts hospitals survive.”

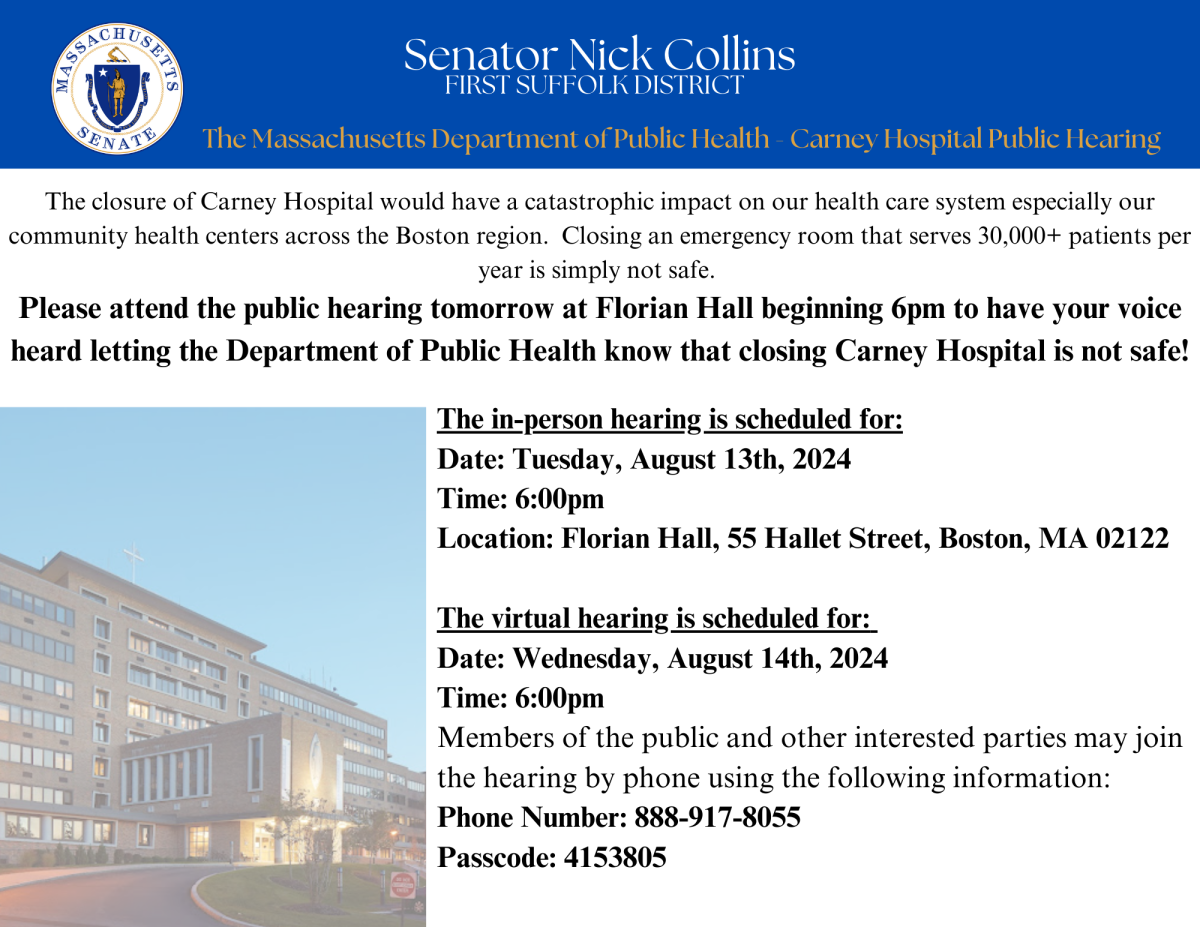

Above, a notice circulated by Senator Nick Collins calls on constituents to voice their support for Carney Hospital.