December 31, 2024

The annex at the Boston Latin School. Chris Lovett photos

The Boston School Committee began its last meeting in 2024 on Dec. 18 with a cheer for inclusive education, only to end three hours later with slightly tweaked plans for rationing coveted seats at three exam schools.

The state’s 2025 “Teacher of the Year,” Luisa Sparrow, was congratulated for her work with special needs students in grades 5 and 6 at the Oliver Hazard Perry Elementary School in South Boston. But, even before discussion of exam schools, the agenda and public discussion touched on other challenges: from a dwindling number of Black teachers to concerns about how to meet language learning needs for a growing number of immigrant students.

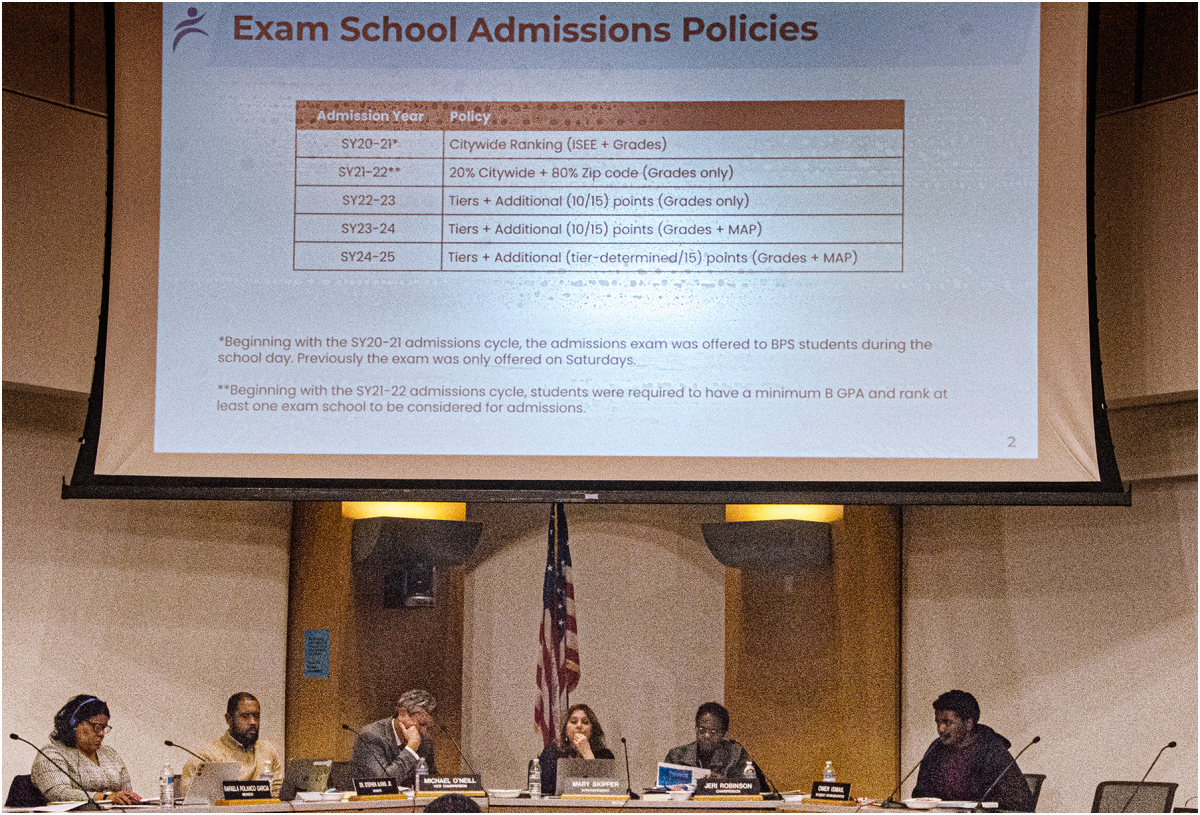

Nine days before the meeting, the US Supreme Court decided against reviewing a legal challenge to the exam school admissions policy that was filed by the Boston Parent Coalition for Academic Excellence. The group argued that the policy’s use of zip codes as a factor in admissions was a “proxy for race” that unfairly reduced access for Asian and white students.

Under the policy, which was adopted for the school year 2021-22 only, 20 percent of the invitations were from a citywide pool ranked by school grades. For the remaining 80 percent, admissions were also determined by zip codes, where the number of invitations reflected the total number of school-aged children – a population that, citywide, is more than two-thirds Black and Latino.

Devised for pandemic conditions, the temporary policy gave way the following year to a policy that used eight tiers for different socio-economic levels based on data from the American Community Survey. Applicants could also receive bonus points for attending a high-poverty school or living in public housing. Starting with applicants for 2023-24, the Boston Public Schools (BPS) also reverted to the pre-pandemic requirement for a specialized admission exam, but with a new test.

In his opinion for the Supreme Court, written a year and a half after its ruling against race-conscious admissions at Harvard University, Justice Neil Gorsuch found that the changes in Boston adopted after the 2021-22 policy were enough to “greatly diminish the need” for review. But, in his dissent, Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. wrote that reducing the chance of admission for one racial group while increasing it for another created a disparate impact that could be viewed as circumstantial evidence of discriminatory intent.

Alito noted that the policy for 2021-22 increased admissions for Black students, from 14 to 23 percent, and for Latino students, from 21 to 23 percent. For white students, there was a decrease, from 41 to 40 percent, and for Asians, from 21 to 18 percent—both figures still well above their share of the city’s entire school-age population.

Chris Keiser, an attorney with the Pacific Legal Foundation representing the Boston Parent Coalition, reasoned before the decision that the temporary policy harmed unsuccessful applicants who might have otherwise been admitted. “Losing out on the chance to go to a school like Boston Latin is no laughing matter, because it’s a nationally recognized school,” he said, “so there’s certainly a penalty that you pay when you work your whole life to try to get into this school and then you’re not subject to the same fair process that the classes before you were.”

Supporters of the more recent policies, including Lawyers for Civil Rights, have contended that the admissions process used before the pandemic was unfair. The group’s litigation director, Oren Sellstrom, estimated that a new challenge, even to the revised policy for after school year 2021-22, was “unlikely.”

“The current system is even more nuanced than the one that was under challenge in the case that the Supreme Court just denied review of,” he said. “In terms of the legal underpinnings. the policy is very much the same in that it has as one of its goals to ensure fairness and inclusivity across a number of lines – geographic, socioeconomic, and racial, yet it does not look at those factors for any one particular student so much as taking account of all of those factors in the overall admissions process.”

In a presentation at the School Committee meeting, Monica Hogan, assistant superintendent for data strategy and implementation at BPS, explained that the distribution of invitations to students entering the three exam schools as seventh-graders in 2024-25 was “more closely aligned to the distribution of school aged children in Boston.” There were increases in invitations for multilingual learners and students with disabilities. For students who were economically disadvantaged, the share of invitations increased from 35 percent in school year 2020-21 to 49 percent in 2023-24, then decreased to 40 percent for the current year.

Though Hogan did not specify any change in the racial composition of students invited, she displayed a map that showed a geographic change in invitations between school years 2020-21 and 2024-25, with a decrease in the share of students from West Roxbury, Jamaica Plain, Back Bay, and Beacon Hill. There were increases for students from East Boston and parts of Dorchester west of Dorchester Avenue and Geneva Avenue, as well as adjacent areas in Mattapan and around Grove Hall.

Students are currently invited from each socio-economic tier in almost equal numbers, from the lowest level in tier one to the highest in tier eight. There are differences in the number of applicants in each tier, from the most recent 115 in tier 1 to the 270 in tier 8. Most of the census tracts for the lowest tiers are in parts of Dorchester, Roxbury, Mattapan, Jamaica Plain, and East Boston. For tier 1, with the lowest socio-economic rank, the invitation rate was 100 percent. The rates were lower in tier 8, at 46 percent, and tier 7, at 62 percent.

For students entering in September 2024, the BPS changed the use of bonus points, which previously could have excluded some applicants with a “perfect” composite score of 100 points. Instead, all 11 applicants with that score were invited to their first-choice school.

For the next school year, BPS officials propose reducing the number of tiers from eight to four, though still with about the same number of applicants invited from each. “It mitigates changes due to minor variability in the American Community Survey data,” BPS Superintendent Mary Skipper explained, “and it lessens disparities in access between students in geographically similar areas.”

Deirdre Manning, a parent from Dorchester, noted that there could still be boundaries between similar areas, and that a family with applicants in different years could be shifted to a different tier, with different odds of admission, based on changing data from a small statistical sample.

“My concern with that is, even if you reduce the number of tiers, if you still have the higher tiers competing against many more applicants, particularly those who do not receive bonus points,” she said in her public comment, “those students are targeted for exclusion.”

According to Will Austin, the founder and CEO of the Boston Schools Fund, the successive variations in the policy also increase uncertainties for parents. For many BPS parents, that follows the earlier stage of uncertainty over enrollment at lower grade levels.

“Although those changes may seem not significant,” Austin noted, “what they do is they create a lot of uncertainty for people about the rules, and also their possibility of actually getting in. And then, inevitably, if there’s uncertainty, that usually begets people not being as interested or, or there’s not as much demand.”

Skipper said she hoped that the School Committee would approve the consolidation of tiers in January, with more review of the admissions policy and consideration of other possible changes in the spring. For the year ahead, she called for attention to the admissions policy itself, an implementation guide, and supports for students.

Members of the Boston School Committee listen to public testimony during a discussion of the district’s admission process for its three exam schools on Dec. 18, 2024 at the Bolling Building in Roxbury.

“I think the exam schools have done a good job coming up with programming that they believe helps to support all students as they go to the exam schools,” she said, “but I’d like to better codify that, and actually make sure that’s there. And that means looking at how are the students doing that are there.”

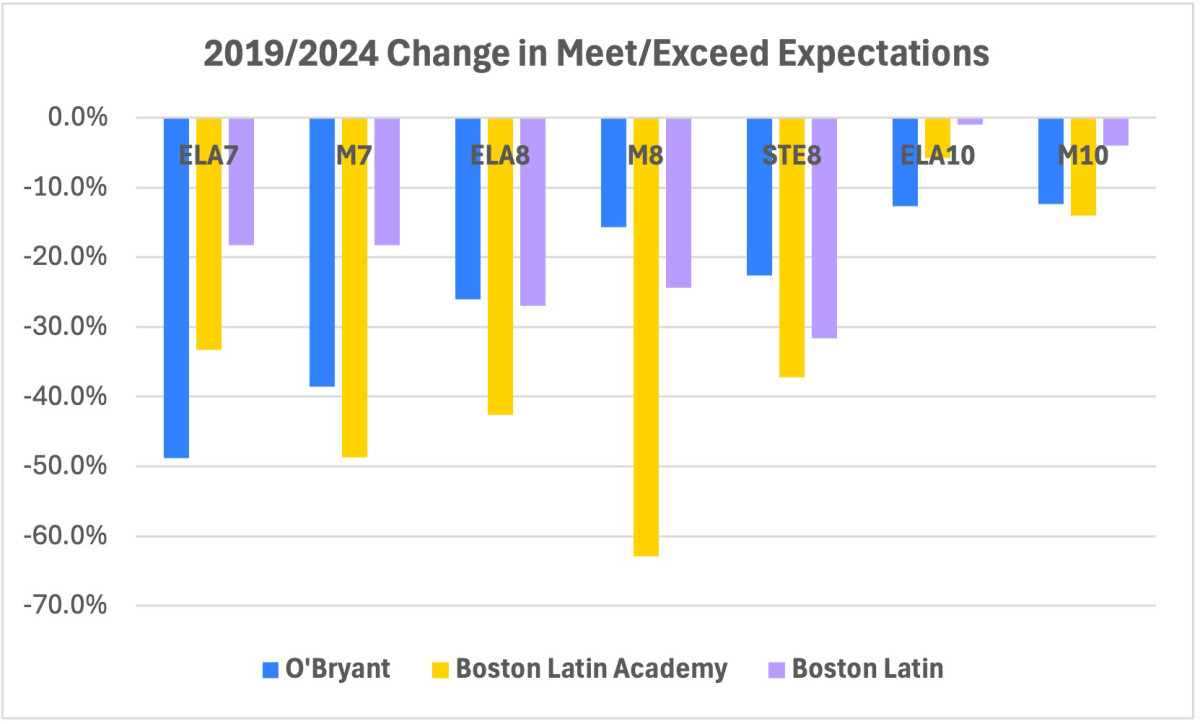

So far, MCAS scores show a gap in results for tenth graders who were invited before the new admissions policy and students in grades 7 and 8 during the school year 2023-24. Compared with MCAS results from 2019, percentages of tenth graders meeting or exceeding expectations were down by single digits at Boston Latin, with most decreases at Boston Latin Academy and John D. O’Bryant Academy of Math and Science down between 12 and 14 percent.

For seventh and eighth graders at Boston Latin, the decreases from 2019 to 2024 were between 18.3 and 31.6 percent. At O’Bryant, the decreases were between 15.7 and 48.8 percent. At Boston Latin Academy, the decreases were between 33.3 and 62.9 percent—with expectations met or exceeded in math by only 39 percent of the 7th graders and only 26 percent of the 8th graders. MCAS results from the schools between 2019 and 2022-2024 also show an increasing gap overall between scores for 7th and 8th graders and students taking the test in grade ten.

A chart shows the changes in testing results at the three exam schools since 2019

US News currently ranks Boston Latin as the number one high school in Massachusetts and number 27 nationwide. The rankings are based on multiple factors, including figures for advanced placement exams and proficiency in math, reading, and science.

In a 2018 report, the Rappaport Institute for Greater Boston at the Harvard Kennedy School highlighted significant racial gaps in the BPS exam school enrollment and in the application process. One change following the report was the adoption of the new entrance exam, replacing a standardized test that included material not covered in BPS elementary grades. Researchers also suggested the use of MCAS scores as one factor in admissions that could reduce the racial gap without compromising student performance.

Another finding by the Rappaport Institute was that Black and “Hispanic” students at every achievement level were less likely to take the admissions exam than white or Asian students with the similar achievement levels. Researchers also found that Black and Hispanic applicants were “substantially less likely” to rank the most prestigious exam school, Boston Latin, as their first choice.

School Committee chairperson Jeri Robinson, left, and vice-chairperson Michael O’Neill listened to public testimony during a committee meeting held at the Bolling Building in Roxbury on Dec. 18. Chris Lovett photos

After the presentation on exam school policy, the School Committee’s vice chair, Michael O’Neill, observed: “We are clearly seeing in the data that we’re getting a wider range of students from across our district. We’re getting more applicants from students who would traditionally maybe not have thought of applying to our exam schools. And those are all positives. I think this proposal on the table simplifies, and also recognizes, some outstanding questions that we need to analyze further and dig deeper on.”

In a remote interview, Sellstrom, of Lawyers for Civil Rights, cited other advantages to increasing student diversity at exam schools. “Certainly, there have been hundreds of studies at this point that show that diverse classrooms are highly beneficial to learning, that students learn from each other as much in some ways as from their teachers, and particularly in the 21st century,” he said. “In the global economy that we live in, it is essential for all of us to be learning from each other.”

According to The Boston Globe, the number of exam school applicants decreased by more than 40 percent after 2020-21, with BPS attributing most of the difference to no longer counting students who were ineligible for admission. In her presentation, BPS’s Hogan reported “modest growth” in the number of applicants from the six lowest tiers, with “a larger decline” from the uppermost tiers.

Tier 8, with the lowest rate of invitations (46 percent), had the highest number of applicants, with only a slight decrease over the past two years. The next highest socio-economic grouping, tier 7, had a larger percentage of invitations, but also a larger decrease in the number of applicants over the past two years, by 24 percent.

Parents, officials, and members of the Exam Schools Admissions Task Force have debated one other possible change: basing the number of invitations for each pool at least partly on the size of its applicant pool. Instead of having a larger but more tightly constricted pool that might discourage applicants, supporters of the change say it could encourage more applicants.

But, as Austin noted, there’s no guarantee that making the shift to using tiers more elastically would have even-handed results. “The whole purpose of this shift is to make sure the exam schools effectively reflected the demography of the city,” he cautioned. “If you start toying with those percentages, you’re going to over-represent one part versus the other.”

Of the exam school applicants who failed to receive invitations for 2024-25, Hogan said, 54 percent are currently attending another BPS school – an increase from the previous year’s figure of 43 percent. As the School Committee’s chair, Jeri Robinson, calculated, that meant “150 higher-achieving kids who BPS now does not have an opportunity to have” in their enrollment.

At the meeting, Robinson and Skipper agreed that there should be more promotion of desirable options in upper grades at other BPS schools. One example, cited by Austin, was the partnership between the BPS, Mass General Brigham, and Bloomberg Philanthropies to expand and transform the Edward M. Kennedy Academy for Health Careers near Mission Hill into what the city hailed in January 2024 as “a national model of career-connected learning.”

As Austin reasoned, the partnership suggests the potential for expanding exam schools – if also increasing the odds that other schools would be left behind. “Even though no one wants to say it out loud, expanding Edward M. Kennedy by a couple hundred kids and adding grade seven and eight puts additional pressure on other schools that are under-enrolled,” he acknowledged. “They’re already making decisions that are creating these pressure points, so I think it’s a little bit of a false critique to say that you can’t do that with exam schools because they’re doing it already with other schools.”

The number of exam school applicants also reflects decisions made earlier by parents, including many who leave the city by the time their children are five years old. According to the Boston Indicators research center at The Boston Foundation, BPS enrollment has been declining since at least 1940.

The exodus of white families after the start of desegregation in 1974, but in even greater numbers in the decade before 1960, has given way to another trend. According to a December 2022 report from the Boston Schools Fund, the highest rate of decline for the BPS between 2019 and 2023 – 17.8 percent – was posted by Black students, with the second highest rate for Asian students.

At the School Committee meeting, BPS interim CFO David Bloom announced that net enrollment changes within a school year, from October to June, have been climbing for the past four years, with an additional 973 students in the course of 2023-24. As explained in a slide presentation, “This growth was driven almost exclusively by an influx of new Multilingual Learners.”

Even in a 2020 Boston Indicators report, Latinos were the system’s largest population, accounting for 42 percent of the students – much higher than the figure for multilingual learners invited to the exam schools. And, though the BPS recently announced an expansion of programs for those learners, advocates and parents continue to call for more resources to bridge the language gaps for students and their families.

One other trend that the Boston Indicators found locally and in other cities was the loss of middle-income families with kids – often families with too much income for subsidized housing and too little for market housing in the city.

“Much of what’s driving these changes in household composition by income is the broader macroeconomic trend of increasing income inequality nationwide,” researchers concluded. “Over the past few decades, the gains of economic growth have increasingly gone to those at the very top of the income distribution, and wages at the middle of the income distribution have stagnated as a result.”

For exam schools with a traditional mission that coupled excellence with equal opportunity, the trend adds more strain, in contrast with earlier times when the link between academic superiority and material advantage was either less prevalent or less apparent. Austin, a Boston Latin alumnus who entered the school in the late 1980s, said that when he came back for a visit twenty years ago, he noticed a difference, even judging from the students’ clothing and backpacks.

“It was very evident for me, just looking around and saying, ‘These kids have more money – these families who have these kids – they have more money,’” he recalled. “I think that’s actually less a reflection of the school’s admissions policies and more a reflection of how dramatically the city has changed, in how we have less of a middle class in the city than we once had – and more of a upper class and a kind of working-poor class that we didn’t have before.”