March 13, 2024

Dennis Lehane giving his author talk on March 3.

Screen shot from BPL presentation

Transitioning from the solitude of writing to the teamwork of TV production, Dennis Lehane took on a different role on March 3 at the Boston Public Library in Copley Square: as a storyteller in a room full of people.

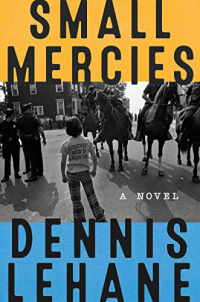

Sharing the platform in Rabb Hall with BPL President David Leonard, Lehane was on hand for an “author talk” about his latest novel, “Small Mercies.” It’s a fictional story that unfolds during the explosion of racial acrimony and violence at the start of desegregation in Boston’s public schools in 1974. But there was also a non-fictional backstory, about a Dorchester native currently based in California who starts writing the book amid the upheaval of the Covid-19 pandemic, while working on a TV project in New Orleans.

“We were staying in this haunted mansion in the heart of New Orleans, and I was just like writing away. And I was transporting myself very quickly to 1974 Boston,” he recalled. “It was wonderful. So, the book just flowed right out of me. It came out in six months and was the most pleasant writing experience I’ve had in probably thirty years. Which is weird, because, if you read the book, it’s pretty dark.”

“Small Mercies” is disturbing on multiple fronts. Its protagonist, Mary Pat Fennessy, is a single mother in a South Boston public housing development whose daughter, Jules, is about to start her senior year at South Boston High School, the epicenter of the clash over what the neighborhood calls “busing.” The night before the first day of school, Jules goes out with friends and never returns home. What people who knew what happened try to cover up is that she was murdered by a neighborhood gangster, in a criminal act meant to cover up something else.

On yet another front, Mary Pat learns that a Black coworker, Calliope Williamson, has lost a son who was killed in a racist attack near the border of South Boston and Dorchester, at what was then known as Columbia Station. In her first reaction to the attack, when seeing it reported in a newspaper, Mary Pat is quick to blame the son, Augustus “Augie” Williamson, for either dealing drugs or, at best, disregarding common sense about Boston’s racial boundaries after dark. What she doesn’t know at this point is that the attackers were Jules and her friends. What would take longer to sort out is how her daughter’s role was more conflicted.

As the story develops, so does Mary Pat’s thinking. At the beginning, she’s ready to demonstrate against “busing.” She’s at home with norms of racial distancing and hostility to more privileged outsiders who look down on her neighborhood. “As a project rat herself,” Lehane wrote, “Mary Pat knows all too well what happens when the suspicion that you aren’t good enough gets desperately rebuilt into the conviction that the rest of the world is wrong about you. And if they’re wrong about you, then they’re probably wrong about everything else.” In other words: She’s an outsider who thinks of herself as an insider.

When people in the neighborhood, including her own sister, close ranks in a code of silence about what happened to her daughter, Mary Pat realizes that she’s an outsider even in her “hometown.” The social contract of Southie pride and reciprocal loyalty is revealed as a cover for one more power structure, refined by privilege but enforced by violence.

Starting as a detective in search of straight answers, while distrusting neighbors and police, Mary Pat becomes an avenger of gathering force. Early on, at a bar, confronting a friend of her daughter who lied about what happened, she breaks his nose and piles on with a flurry of punches. If she’s part of a social construct, she’s also a human agent or, as Lehane put it, a composite of “fearsome women” from projects and three-deckers he remembered from when he was growing up.

“The image that I got that led me to start the book was I saw a woman beating the… out of a 19-year-old man in a bar,” said Lehane. “And I thought, ‘I like this lady. She’s cool!’”

Many books have been written about Boston’s racial divisions and the upheaval associated with the term “busing.” Among the most direct accounts is the acclaimed memoir “All Souls” by Michael Patrick MacDonald, who grew up in South Boston’s Old Colony public housing development. The book is a requiem for lives destroyed or derailed by turmoil in the schools, predatory gangsters, and drugs, but also a testimony to the long reach of trauma.

A son of Irish immigrants who was nine years old in 1974, Lehane grew up in a Victorian house in an area known to many of his neighbors as St. Margaret’s Parish. If that was a far cry from public housing in South Boston, it was still part of a whole city in the grip of intense racial acrimony that sometimes erupted in acts of violence—even into the 1980s.

“I had always had this anger in me that I could never understand, because it didn’t fit with biography,” Lehane confessed. “My parents were great. I grew up well, loved. I was not abused in any way by anybody. Yet there was this – I had this hair-trigger temper, and it wasn’t just an Irish temper. It was like this deep rage inside of me. And, in writing this book, it all came out. It all came out.

“And I understood it, finally. I was a very off nine year old, because I was like, ‘How dare you take my childhood?’ Because that’s what I feel like the summer of ‘74 did to you, when you’re walking around on the streets and you see KKK in Boston – believe me, and I did. Or you see, ‘Kill all the n-words in Boston,’ or you see people throwing rocks at buses with children in them. You can’t be a kid. You can’t. It stops. It stops right there.”

Though many of Lehane’s books have Boston settings—or something recognizably similar – he said that “Small Mercies” had a kinship with his first novel, “A Drink Before the War,” published in 1994, just a few years after Boston’s spike in youth violence. Even in the earlier book, Lehane plots neighborhood boundaries, whether physical, mental, racial, and economic, or between those with connections and those without.

Here’s Lehane on a racial divide at close range, as applied by a white Dorchester detective, Patrick Kenzie, to himself and the Black cleaning woman, Jenna Angeline, whom he has been hired to locate after she mysteriously disappears: “In my Dorchester, you stay because of community and tradition, because you’ve built a comfortable, if somewhat poor existence where little ever changes. A hamlet. “In Jenna Angeline’s Dorchester, you stay because you don’t have any choice.”

A more nuanced view might also see a white Dorchester where connections are frayed, or a Black Dorchester that’s nurtured by choice. More important for Lehane is how a sense of boundaries can trump geography, for example, by writing off violence as a “Roxbury” thing. As Kenzie reflects, “Black Dorchester gives up its young on a pretty regular basis, too, and those in White Dorchester refuse to call it anything but the ‘Bury. Somebody just forgot to change it on the maps.”

As demographics change, fudging the map keeps “outsiders” at a distance, closing ranks in a hamlet where everybody knows your name – fortifying the status of being an insider. There’s only one more step to the distinction between perception and profiling, as unapologetically exemplified by one of Kenzie’s white friends: “When I drive through my neighborhood, I see poor, but I don’t see poverty.”

In the author talk, Lehane also brought the discourse on boundaries closer to home, within his own family.

“My father was against busing. My father was also against racism. That was a paradox that I think got swept away, and so, if you were against busing, you were clearly a racist,” he explained. “My father wasn’t against busing because he didn’t want his kids to mingle or to have African Americans in his neighborhood. We had African Americans in my neighborhood, but he was against busing because it was one more time that the powers that be came in and told the poor neighborhoods how life was going to be. And he remembered when you could see the ocean in Dorchester. And I grew up, going, ‘There’s an ocean?’ Because they dropped 93 right in. They didn’t drop 93 through Newton.”

Lehane acknowledged there were some in the neighborhood whose racial antagonism was less filtered or conditional. He also admitted that the father he admired for preaching equality could express anxiety about racial change in the neighborhood’s housing—that is, while blaming racist attitudes of other whites for hurting his property value. For a boy, as Lehane put it, the mixed messages were “very confusing,” but also a cue to proceed with caution, almost as an outsider blending with insiders.

“To be nine years old and surrounded by everybody in your tribe who thinks this is fine, yeah, your tribe, pretty much everybody you hang out with, all the houses you go visit. Not all of them, but a lot of them,” he explained. “And, so, you feel like a spy from the very beginning.”

Eight years later, in 1982, and one parish away, a Black man, William F. Atkinson, was killed after being chased into Savin Hill Station by a group of white attackers who were just a few years older than Lehane. Many white residents in Dorchester, including some in the Savin Hill neighborhood, were quick to publicly denounce the attack. Others tried to shield the attackers or bring up crimes against whites in Black neighborhoods. Lehane recalled a similar pattern.

“The thing that I remember – oh God – I remember this throughout my childhood,” he said, “was the ‘what-about-this?’ Constantly, you would say they’re throwing rocks at buses. ‘Well, what about that girl who was stabbed in Roxbury the other day?’ Right? But they’re throwing rocks at buses! ‘But what about…’ It was constant. It was a constant way to deflect, deflect, deflect.”

The violence at Savin Hill Station has its fictional counterpart in “Small Mercies,” with the attack on Augustus Williamson at Columbia Station. When Mary Pat goes to his funeral and tries to express condolences to his family, the attempted reconciliation misfires. Instead of a fellow survivor bonding in sympathy, she’s viewed as part of the problem. Up to this point, she doesn’t get it, still hemmed in by her inverted sense of exclusion, cloaked as tribal solidarity—a mindset that caused her last husband to walk out on her.

“She’s in complete denial,” said Lehane. “The journey of the book is so that, by the end of the book, she understands exactly what he means. She has to come to terms with who she is.” She also illustrates what James Baldwin meant in his 1962 essay about the need for writing to engage with disturbing particulars: “Not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

Fifty years after 1974, Lehane sees Boston’s desegregation remedies as flawed by planners and constrained by a US Supreme Court decision that ruled out any extension of mandatory busing to schools in the suburbs. And he does not see much progress toward quality education in the Boston schools. But he also maintained that the level of antagonism to desegregation in South Boston would have been the same in any other white community.

“Busing,” he said, “taught me this – not busing, but the reaction of busing: It is always in the best interest of the ruling class to keep the working class fighting amongst itself. I believe that to my heart and soul. One of the easiest ways to divide people is along racial lines.”

Lehane also knows that the divisions in Boston, whether in race or class, go back more than a century. That was the source of tension in another of his novels, “The Given Day,” which was set in 1919. It was a year marked by racism, xenophobia, low wages, labor unrest, terrorist actions, government crackdowns, the Boston police strike – and a deadly pandemic.

One of the main characters in the book, Danny Coughlin, is a second-generation police officer forced by the escalating labor conflict to know which side he’s on. He’s hardly an underdog in public housing and, in the early chapters, he mentally pledges allegiance to some idea of common good: “It was tied up in duty, and it assumed a tacit understanding of all the things about it that need never be spoken aloud. It was, purely of necessity, conciliatory to the Brahmins on the outside while remaining anti-Protestant on the inside. It was anticolored, for it was taken as a given that the Irish, for all their struggles and all those still to come, were Northern European and undeniably white, white as last night’s moon, and the idea had never been to seat every race at the table…”

Like Mary Pat early on, Coughlin, at this stage, is an outsider mentally positioned as an insider. But, for all the flux and shifting perspectives among his characters, Lehane described his own compass as anchored somewhere else.

“I can only write from the outside looking in,” he said. “That’s what I understand of the world. I was always an outsider. If you grow up working-class, you’re an outsider. If you grow up and people treat you differently when they hear where you’re from, that’s not nearly as bad as being treated differently because of the color of your skin, but you notice it.”

Amid the 21st century pandemic, Lehane finds his way to Mary Pat, following the path of his rage and writing a book that he described as an “exorcism.” Like Walter Benjamin’s “Angel of History,” he looks back and surveys the wreckage, just as he did with the smoldering prologue in “A Drink Before the War,” haunted in the 1990s by the late 1960s and early 1970s. Decades later, basking in enthusiasm for his work in television—including a possible adaptation of “Small Mercies” – he said the book could very well be his last, or at least the last to meet a publisher’s deadline.

“This book came from a place that my first book came from, which is that it came from a very pure place. It just flowed out of me,” he said. “And I wrote it because I needed to write it. And I thought that was wonderful. And the moment I finished it, and I turned it in, I was out of contract all over the world. And I thought: I’m good with this. And if I write another book again, it’ll be because it comes from the exact same place.”