January 4, 2024

Ted and Linda Loska show off the new speed hump near their home on Larchmont Street. Larchmont is one of many streets in the Bowdoin-Geneva area that has benefitted from a quicker plan to install speed humps ahead of larger street improvements in the city’s Safety Surge program. The Bowdoin-Geneva and Hancock Triangle program represents the largest street safety undertaking yet for the city. Seth Daniel photos

Efforts to slow down driving in Dorchester have increased in intensity over the last few months with speed hump installation being prioritized across the neighborhood. Bowdoin-Geneva and the Hancock Street Triangle are the latest named as key areas where a new program will focus on quick fixes and long-term changes to enhance safety for drivers and pedestrians.

Over the past month, speed humps have been installed on streets across Bowdoin-Geneva as the first implants in a long process known as the Bowdoin-Geneva Transportation Action Plan, and humps are expected as soon as this month for streets in the Hancock Triangle. They will be followed by more long-term changes to side streets and thoroughfares like Westville and Hancock streets in early 2024.

This push involves the largest swath of neighborhood streets and arteries tackled by the city to date in its Safety Surge program (formerly dubbed Neighborhood Slow Streets), and it will serve to refine how to bring in improvements at a faster pace.

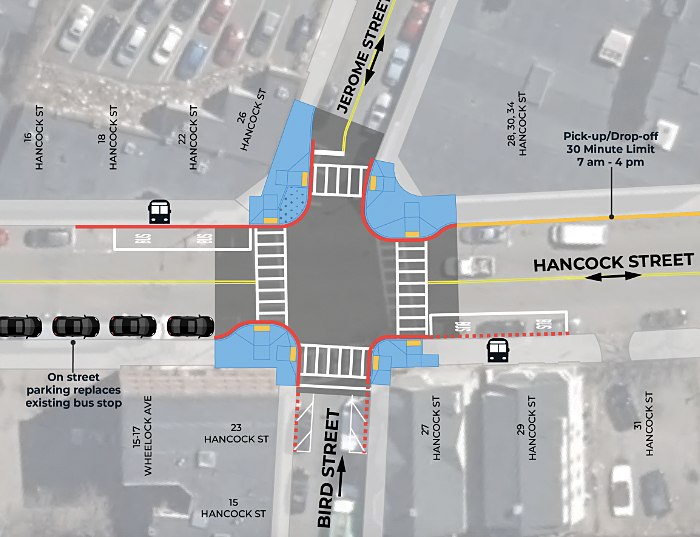

A city of Boston graphic outlines proposed traffic calming measures in the works for Hancock Street.

In addition to the push in Dorchester, two zones in South Boston and one in East Fenway had speed humps installed over the last few months, with “lots more” in design.

“We’re really trying to move away from the (Neighborhood Slow Streets) model where the lucky few get safety improvements,” said Jascha Franklin-Hodge, chief of streets for the city. “I believe the zone in question under the Bowdoin-Geneva Action Plan is larger by a significant amount than any Neighborhood Slow Streets program so far. It is the first time we’ve done a neighborhood-wide plan this large that combines the quicker improvements like the speed humps and the larger, more robust improvements as well.”

It was surprising that the humps began to appear in November and December throughout the Bowdoin-Geneva corridor and in September in the St. Brendan’s neighborhood. They weren’t expected in either place until the new year and beyond, but Franklin-Hodge said, the city had re-tooled its plans.

He noted that humps are in such demand in the neighborhoods that qualify for them (they cannot be set on a major thoroughfare or one with an MBTA bus route) that the long-term plan wasn’t realistic. So, the city quickly pivoted to more speed humps, with plans to follow for long-term improvement like raised crosswalks, curb bump outs, and intersection rebuilds.

“We took the speed hump zones for the Safety Surge out,” he said, “and brought it forward faster and got it done this year and in 2024 we will go forward with the start of the reconstruction plans,” pointing to Bowdoin-Geneva as the first to follow that pattern.

“We’ve engaged two dedicated contractors only for speed humps,” noted Franklin-Hodge. “They’ve built 144 speed humps and can build dozens a day. They can do more over the winter as long as they can get an asphalt plant to stay open.”

Residents have taken notice of the safety surge with satisfaction.

Ted Loska, of the Greater Bowdoin Geneva Neighborhood Association (GBGNA), said they found speed humps on Larchmont Street a very welcome addition. “We are very pleased to have our street included in the traffic calming program,” he said.

Bowdoin-Geneva was chosen for the rollout because there was an existing road map for changes, and implementation was key.

Davida Andelman has been involved since the city began talking about the plan in 2019, watching it grow from a $100,000 study of the intersection of Bowdoin Street and Geneva Avenue to a comprehensive plan all the way up Hancock Street. She said the association had told the city from the start that it needed to be a more comprehensive plan with more voices and more neighborhoods.

While some residents were surprised, even concerned seeing things expand all the way to Four Corners, then through Hancock Street, the rewards were noted with smiles when speed humps recently were installed on Hamilton Street.

“The bigger work needs to be done still, but overall, I think everyone is pleased this thing is up and visible and doing something,” said Andelman. “The feedback I’m getting from neighbors and my own unofficial survey…is for the most part that people are thrilled. There are those folks to our chagrin who don’t think it will do anything. Other people say we need more of them in other locations. Bottom line is it really does make a difference and we’re very happy about that.”

She noted that one piece hasn’t yet been figured out: enforcement. “There just aren’t enough people in the Police Department to really enforce the way traffic laws need to be enforced in the city.”

There are about 30 streets in Bowdoin-Geneva, from Park/Claybourne streets across to Columbia Road/Quincy Street that have gotten speed humps already or will soon get them. In the Hancock Triangle, there are approximately 17 streets that will see speed humps installed as early as January and into the spring – stretching from Meetinghouse Hill to Uphams Corner and connected to the Bowdoin-Geneva plan by Quincy Street.

For the bigger work on Bowdoin-Geneva, Franklin-Hodge said, a car crash death in July 2022 on Tonawanda and Greenbrier streets has elevated that area’s priority within the Bowdoin-Geneva planning area.

“There are a couple of pressing areas, one is Tonawanda Street coming into Mother’s Rest Park and around UP Academy and the Marshall Community Center at Westville and Dakota,” he said, citing the 2022 crash.

“Any time we’re pouring concrete and digging we know it’s a much more difficult project; any time we have a project like that, we’ll prioritize,” he said. “It’s one of the challenges we have with doing these safety projects. With a residential street, we can put speed humps, but with our larger intersections we want to do more.

“Our arteries like Hancock are the real challenges because we need them to function as arteries, but we need them to be safe as well, so it’s a little balance.”

Plans are very detailed for the Hancock Triangle area – with safety improvements like raised crosswalks and curb bump outs planned for the Hancock Street corridor at Bird Street, Trull Street, Rill Street, and in front of the Conservatory Lab Charter Lower School. Meanwhile, major attention is also being paid to the convergence of Bellevue, Stanley, Ronan, and Trull Streets on top of the hill behind Uphams Health – a very confusing intersection with two parks, a school, and the health center in close proximity.

The plan is to add curb extensions to several parts of the intersection, particularly in front of Stanley-Bellevue Park, and a raised crosswalk between Ronan and Trull Streets. There will also be new parking restrictions along Bellevue, Stanley, Trull, and the curb at Ronan. The final piece is to convert Bellevue Street between Quincy and Ronan Streets to a one-way toward Ronan. It will run in the opposite direction of Stanley Street.

These are mechanisms, Franklin-Hodge said, to address input that they got about crosswalk crowding, blocked sight lines, and cars parking too close to the curb – things that are already illegal but not easily enforced.

“Some of it is really only making sure the existing rules are followed,” he said. “Sometimes it is the parking that is the safety problem. We want to be thoughtful and judicious about where we need to block it off in the residential areas.”

Having Bowdoin-Geneva and the Hancock Triangle addressed for street calming now brings a huge portion of Dorchester into a unified program. Since 2017, adjacent neighborhoods like Talbot-Norfolk-Triangle, West of Washington, Dorchester Unified East and West (Norfolk Street corridor), Redefining Our Community (ROC), West Selden Street, Washington-Harvard-Norwell, Grove Hall Quincy Corridor, and St. Brendan’s have been built out.

Franklin-Hodge said the city hopes those measures will bring about a new norm in how people drive when navigating neighborhoods. “The goal is to have a future where you don’t know you’re in a special zone because you get into a neighborhood that’s safer and slower. We hope all our neighborhoods look like that in the future. We hope the default becomes that you operate slower and more respectfully once in a neighborhood context…That’s a broader attitude shift around neighborhood street driving.”

For more information on the projects, visit the city’s project pages for Bowdoin-Geneva Transportation Action Plan and the Hancock Street Triangle.

Traffic light issues are getting attention – and federal funding

Another piece of the neighborhood street safety puzzle involves traffic signals and lights around the city, particularly in Dorchester and Mattapan where there are high-crash corridors and dated signal equipment that is beyond obsolete.

The city’s chief of streets, Jascha Franklin-Hodge, said that it is part of an overall plan to address street safety within the existing Safety Surge program that was given a boost last month when the city scored a $14.4 million federal grant from the Safe Streets and Roads for All program funded by the US Bipartisan Infrastructure Law passed in late 2021. That money will complement $9 million received in an earlier funding round and already spent, as well as city dollars to address the signals and intersections.

All told, there is $19 million now available to address the mix of changes that, Franklin-Hodge said, range from adjusting signal times and adding a lead pedestrian crossing signal – costing around $10,000 – to things like a $1 million total intersection rebuild. He said they have identified the areas that need the most work, and many are in Dorchester – such as the Washington Street corridor and the intersection of Blue Hill Avenue and American Legion Highway.

“We have a lot of high-crash corridors,” he said. “Washington Street in Dorchester is like that at almost every intersection. Every intersection needs lead pedestrian intervals and major signal upgrades.”

A challenging part of this puzzle is that Boston is said to have some of the most antiquated traffic signal equipment in the country. Franklin-Hodge didn’t go that far but he did say the challenge is that making simple safety changes often requires major investment to replace outdated equipment.

“We know where we need to do work and we’re trying to pull the resources and money together to focus on places where we know we can do the most good,” he said. “We have some very old signal equipment, and it limits what we can do. Even to do simple stuff like a lead pedestrian signal can’t be done on some of them because they don’t have computer equipment to make that change.”