May 30, 2024

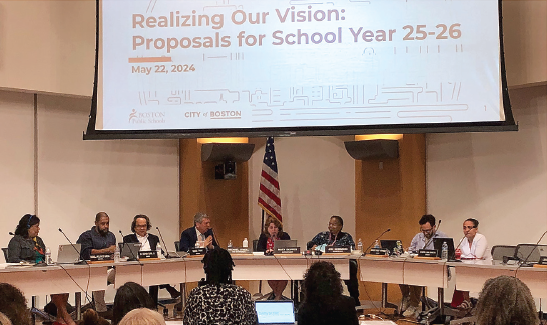

The Boston School Committee and BPS Superintendent Mary Skipper discussed the BPS Facilities plan during a public meeting at the Bolling building in Roxbury on May 22. Chris Lovett photo

Despite a decrease in student enrollment by 15.2 percent since 2014-15, officials have unveiled a long-term facilities vision for the Boston Public Schools (BPS) without identifying a single building that would close permanently. Instead of counting buildings and rooms, the presentation at the May 22 meeting of the Boston School Committee, led by BPS Superintendent Mary Skipper, repeatedly emphasized increasing the number of “quality seats.”

The outline called for a phase-out of the Lilla G. Frederick Pilot Middle School in Dorchester at the end of the 2024-25 year. The move had been announced in January, as part of a system-wide realignment that would group 7th and 8th grades with high schools.

At the meeting, BPS and city officials said the Frederick’s current sixth graders would be transitioned over the next year to attend new schools in 2025-26, with a program for multi-lingual learners moving to Margarita Muñiz Academy, a dual language school in Jamaica Plain.

“We are committed to maintaining the name of Lilla G. Frederick for the building and continuing to use the building as the school to serve our younger people in Grove Hall and throughout the region,” Mayor Michelle Wu’s senior advisor for youth and schools, Rebecca Grainger, told the School Committee. The plan calls for any new school in the building to have community partnerships. Instead of being left vacant during a period of transition, the school building would continue to be used for community purposes.

The only other building change identified for 2025-26 was the consolidation of the West Zone Early Learning Center with the James W. Hennigan K-8 School in Jamaica Plain. Both schools currently share the same complex, which would be reconfigured to serve grades PreK-6. Officials say the ongoing realignment would reduce the number of potentially disruptive school transitions, as well as the over-capacity that typically resulted at K-8 schools when 7th graders left for exam schools or other options.

But, even before the presentation on facilities, Skipper drew attention to the overlap between under-enrollment, under-performance, and chronic absenteeism in the system’s open-enrollment high schools. She noted that most of these schools have also been identified by the state as needing assistance or intervention.

“What you see is that the multilingual learners and our special education students are really concentrated in our open enrollment schools. It is those open enrollment schools that are actually under-enrolled and under-utilized from a building perspective,” she explained. “However, we can’t just simply close or merge them without first developing a way for the students who are in them, who are the most fragile, who are our multilingual learners, and students with disabilities, to have seats in other places.”

The response, outlined by BPS officials, was to expand inclusive learning, with programs for language learners and special education students. The vision also included more access to internships, advanced placement classes, and early college pathways—options that could also create more incentive for attendance. And, as Skipper insisted, any students displaced by a closing should transition to a school that serves their needs.

“We cannot close our way out of this,” she said “We have to do both. We have to develop the programming and the strong academics and remove the barriers, and we have to work on our buildings.”

The presentation listed eleven major capital projects underway, some initiated before the current city administration. These included a merger between the Shaw and Taylor Schools in Dorchester and Mattapan, and a funding application to the state for the Ruth Batson Academy in Dorchester. Skipper said the projects “represent more than we did in forty years,” adding, “These projects unlock high-quality seats at a faster rate than we have ever done, but we need to do them well.”

The changes for the Lillia G. Frederick Pilot Middle School and the Hennigan School complex ae scheduled for a vote by the School Committee on June 17. After helping students make transitions over the coming year, Skipper said there would be annual review of data, engagement with communities, resulting in new proposals each year.

“I understand why some community members are asking for a specific year-by-year roadmap,” she said, “but this work is so intertwined with the core academic and structural changes we’re making from inclusive ed to the expansion of bilingual programs to the expansion of secondary school pathways. We have to move carefully reviewing the data each year and making adjustments to make sure we are continuing to put students first.”

During the meeting and after, the presentation was criticized for decisions made with little advance notice for school communities and for a lack of specification about needs and capacity. A long-time educational advocate, John Mudd, called the limited number of short-term changes a “piecemeal” approach.

“Where is the overall master plan? Where are the proposals that meet the challenges of this moment?” he asked during the meeting. “I should also add that in none of these proposals was there any analysis of the impact on enrollment or the budget. But, critically important, the process used in presenting these proposals to the affected school communities does set a precedent for community engagement. And this precedent is totally inadequate.”

The presentation was also criticized the day after the meeting by Will Austin, CEO of the Boston Schools Fund.

“What was released on Wednesday night is not a facilities plan. Nor is what was submitted to the state in January,” Austin wrote. “The City has communicated a set of values, ideas, and priorities and a commitment to name projects annually. Although that approach provides for flexibility and community input, it lacks the information and transparency about enrollment, potential projects, timeline, and budget that is typical in long-term facilities plans.”

In 2011, after a 13 percent drop in BPS enrollment during his first four terms as mayor, Thomas M. Menino closed or merged 18 schools. Four years later, with fewer constraints on the budget, his successor, Marty Walsh, started work on a ten-year facilities plan that called for new buildings, renovations, and closings. Since 2015, the steepest fall-off in BPS enrollment has come with the pandemic, followed by increases after 2021, including an influx of 3,000 migrants, according to Skipper.

During the presentation, the BPS Chief of Capital Planning, Lavern Stanislaus, cautioned that under-enrollment should be viewed, not just as space, but as a mismatch between students and needs.

“It’s not that we have too many seats,” she told the School Committee. “It’s that we don’t have enough high-quality seats, particularly for students with particular learning needs. Closures will be a part of our long-term work, but we need to continue to invest in our schools for both in terms of high-quality instruction and in terms of facilities so that all students have access to great schools.”

But Austin argued that moving more slowly also had a cost. “If done correctly, a capital budget unlocks funding that should go to classrooms, educators, and children,” he reasoned. “In the past five years, the city of Boston has spent nearly $200 million on empty seats in school buildings. Those are dollars that could be addressing literacy, career and college readiness, the influx of migrants, and other pressing needs.”

School Committee member Brandon Cardet-Hernandez added the possibility that changes made by a rolling facilities plan could end up being unraveled by elimination of an estimated 8,000 unfilled seats. The changes would also take place amid expectations of growing pressure on the city budget and a full election year in 2025.

“We have to merge schools,” said Cardet-Hernandez. “Does it not become more difficult to unravel the pieces, or is it then just about performance and outcomes? I don’t know what comes after that, if that makes sense. If every seat is high-quality today, you would still have to merge schools.”

The School Committee’s vice chair, Michael O’Neill, said he was expecting more closures or consolidations, but he praised the presentation as “a pretty clear roadmap” for the BPS decision process. “I have to applaud your thoughtfulness on this,” he told school officials, “and I do think you have thought through what hasn’t gone right in the past and what has been wrong to our students--and how can I do this the right way.”

Also comparing the presentation to past decisions was the School Committee chair, Jeri Robinson.

“And the issue is how are we helping every community to understand that there will be impacts,” she said. “We say we want change. We know we need to change, but we can’t be afraid every time any change is proposed that everybody’s going to have an outcry.”