September 14, 2023

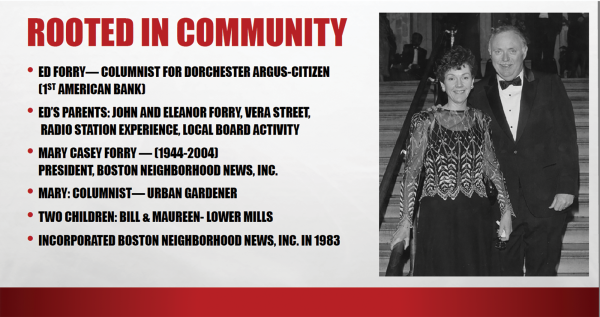

In 1983, Ed and Mary Forry launched a monthly newspaper from a makeshift office in their Lower Mills home. Forty years later, The Reporter is still in business and the Forry’s vision of creating a quality hometown newspaper for Boston’s largest neighborhood remains a weekly work in progress.

When he left his home near Dorchester Park that Monday morning in August of 1983, Ed Forry had a lot on his mind. It was three days before his 39th birthday, and two months after he had quit his job as a savings bank officer in what his wife Mary called his midlife crisis.

It was a summer of dismay. To keep up with the mortgage and household expenses and to buy clothes for the two kids, Bill and Maureen, and to pay tuition at St. Gregory’s, they had tapped into his $5,000 pension fund. As days turned to weeks, worry turned to panic. “You’ve got to do something,” said Mary. “Whatever it is, I’ll support you. Just do something!”

But what? He wasn’t trained for much. He had written a few columns at Boston College and later for the Dorchester Argus-Citizen. At Boston University, he had studied urban affairs, and he knew that neighborhood news was important.

Then, he had an idea. It began as a crazy impulse, evolved into reasonable speculation, then into rational discussion with Mary at the dining room table and, finally, into a conviction that it was possible.

Why not start his own community newspaper?

A realistic dream? An audacious fantasy? He wasn’t sure, but he went public anyway, outlining the idea in a letter to a hundred people he knew through the Dorchester Board of Trade, Dorchester Kiwanis, Dorchester YMCA, and Neponset Health Center.

Not everyone thought it was a good idea. Still echoing in his mind were the words of his long-time friend, Paul LaCamera, then an executive with WCVB-Channel 5 and now general manager of public radio station WBUR-FM. Hearing that Forry had quit his job and was pondering the idea of starting a newspaper, LaCamera gave him some advice: “You go right back into that bank tomorrow morning and tell them you’re sorry, that you don’t know what you were thinking, and could you please have your job back.”

But Forry persevered.

Over the summer, at their Richmond Street home, he and Mary moved four-year-old Maureen out of her second-floor bedroom. They converted the 10-by-18 foot space into a newspaper office. He lugged up a desk from the basement. He bought a copy machine. He installed a telephone, with speakers for interviews, and then he withdrew another $500 from the pension fund to purchase the newest computer, an Apple 2-E with floppy discs and what was then the mind-boggling storage space of 64 kilobytes.

On that Monday morning in August, 1983, as he left his home to embark on the first day of his newspaper career, Ed Forry was wearing not only the hat of a publisher, but also enough hats to make him a milliner, for he would have to cover news, write stories, edit copy, shoot photographs and compose headlines. Columns would be his responsibility and the editorials, too, and it would be up to him to sell advertising, serve as his own public relations spokesman and even to fulfill the obeisant duties of copy boy.

On that Monday morning, more than three centuries after establishment of America’s first successful newspaper, the Boston News-Letter, Ed Forry was taking the first precarious steps on an odyssey to establish his own newspaper, the Dorchester Reporter, which is celebrating its silver anniversary this year.

Dilemmas from the Get-Go

The first task, even before covering a news story, was to establish financial viability, and in the newspaper business, that means ads. As he walked up Richmond Street toward Lower Mills, Forry was plagued by doubts. He’d need to earn something close to his salary at the bank, which was $24,000. Unlike the publisher of the Boston-News Letter three centuries earlier, Forry could look forward to no government subsidy, and so he would need -- let’s see, he had done the math over and over in his head -- he’d need $2,000 a month, which is $450 a week, which is a lot of ads.

On that first day, at his first stop, the Liberty Deli, he was confronted by the first of two dilemmas that would challenge his journalistic ethics.

A spirited mayoral race was underway. Among the candidates were Ray Flynn, David Finnegan, Mel King and the man Forry spotted at the Liberty Deli that morning, his old friend from the neighborhood, Larry DiCara. While they sipped coffee, to Forry’s surprise, a news crew appeared from a local television station and began to shoot film and to interview not only DiCara, but also Forry.

In his mind, Forry heard two voices. First was the publicist in him that said the exposure on television would be good for his new newspaper. The second was the editor in him that said, Whoa, Wait!

“It came to me in a flash,” he recalls now, a quarter century later. “I’m a friend of Larry, but should I be all over the six o’clock news with him when I’m starting a newspaper? No, because it would come across that I was part of his campaign, and I realized, suddenly, that being in the news business, there are lines you have to draw.”

The second challenge to his principles came later that day, while he was selling an ad to the head of what is now Meetinghouse Bank in Lower Mills.

“Tell you what I’ll do,” said the bank president. “I’ll commit to a $100 ad once a month for a year. I’ll cut a check now for $1,200, but I want the ad on page one.”

Now, to Forry, a $1,200 check seemed as beneficent as a Congressional buyout to rescue Wall Street, but he did not hesitate.

“No,” said Forry. “There’ll be no ads on page one, only news.”

The banker laughed. C’mon, he said, community newspapers always take ads on page one. Yes, said Forry, but ads on page one might convey the impression that corporate sponsors were involved in producing the newspaper.

The executive was adamant, but so was Forry. In the end, the banker blinked and bought a year of ads — inside the paper, and payable monthly — while warning that if he saw any ad on page one, the deal was off.

Although Forry never had taken a course in journalism, he understood a precept not apparent to some who work in journalism for decades -- that readers cannot trust a newspaper that is not independent in its news columns.

For Forry, these were unchartered waters, and Harvard Business School probably would have been appalled at his decision to set sail on stormy seas with no business plan, no compass.

Having worked at the rival Argus-Citizen, though, he knew the competition was weak.

“It was a Hollywood set,” he says, “a facade with nothing behind it. Circulation was about 1,000 a week, and they had a retinue of advertisers, largely from ad agencies, who got on a list and never got off. They owned the press, had few expenses, and made money hand over fist. My guess is they put out the paper for $500 a week, and ads brought in maybe $4,000 a week.”

By September, 1983, the first edition of The Reporter had been put together in the second floor bedroom converted to a newspaper office, and presses in Hanover were hired to print 12,000 copies, most of them distributed free to homes throughout Dorchester.

Surviving copies are crinkly and yellowed at the edges, but in a box atop page one, Ed Forry’s newspaper introduced itself to Dorchester.

“Hello. This is the very first edition of a new monthly newspaper that will be delivered to your home at the beginning of every month. The main goal of The Reporter is to provide information to you -- news about your church, your school, your neighborhood, your local merchants. We’ll also have advertisements for local businesses and a classified section telling you about local yard sales, flea markets, help-wanted items for sale and the like.”

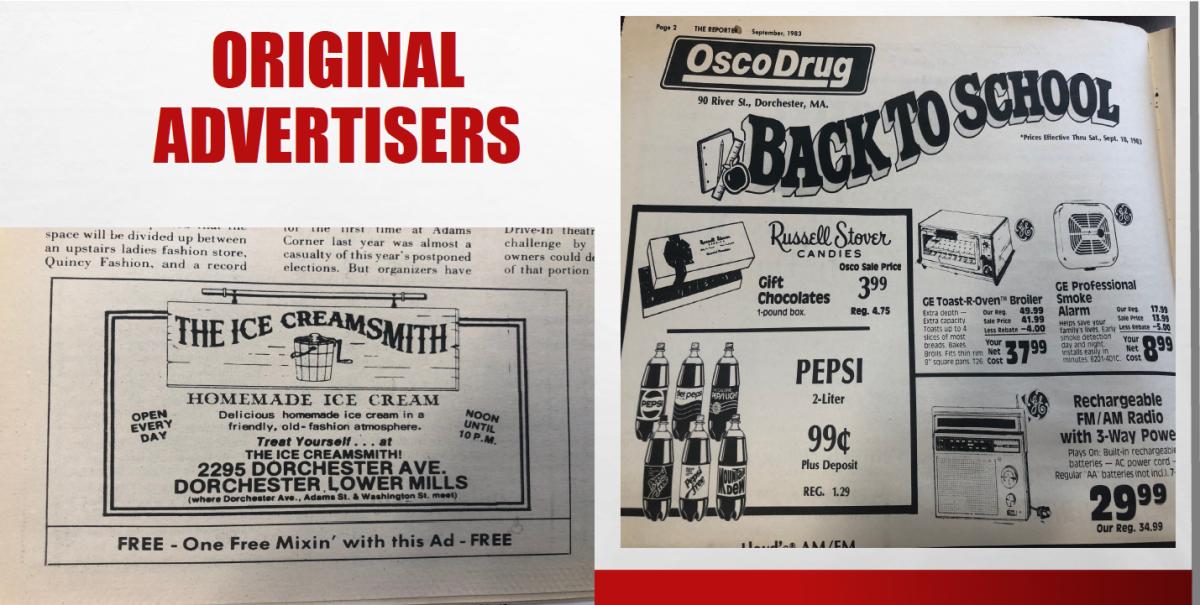

At newsstands, the cost was 25 cents, but what a bargain, for inside were coupons valued at $15 -- coupons that could be redeemed for a half price dinner at the Swiss House, $2 off at Osco Drug on River Street, or a free game of candlepin at Boston Bowl on Morrissey Boulevard.

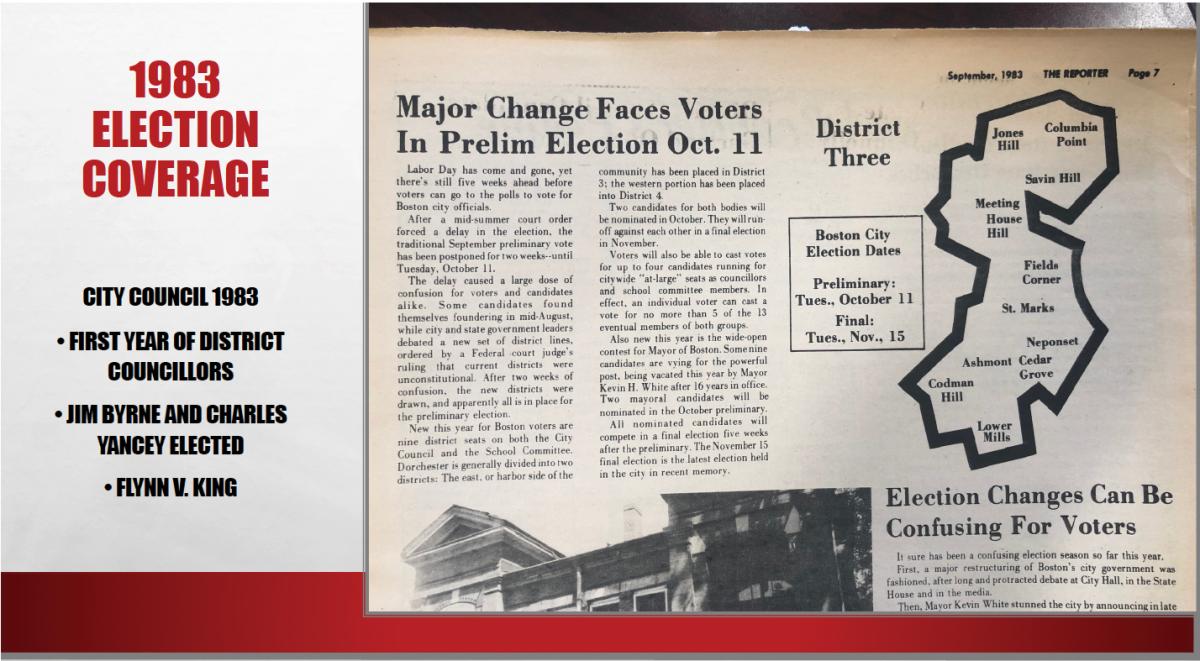

A review of early editions is like an archeological dig. “Cable TV Almost Ready In Dorchester,” said the lead story of the first issue, and inside the second issue were a remarkably detailed account of the mayoral campaign and an easy-to-comprehend manual that deciphered complicated charter changes that altered races for City Council and School Committee.

Early issues included a medley of stories that never would have found their way into a big city daily — registration for toddlers at the Murphy School, open house at the refurbished YMCA, and a reunion at McKeon Post for the old gang from Gallivan Boulevard. Neither the Globe nor Herald was likely to alert readers that the Peabody Square firehouse had a new roof or that Henry Rush was home from Florida, and then, of course, there were the honor rolls, from the saints schools, Ann, Brendan, and Gregory, and public schools, Marshall, O’Hearn, and Murphy.

The newspaper was livened from the beginning by two columnists who became stars.

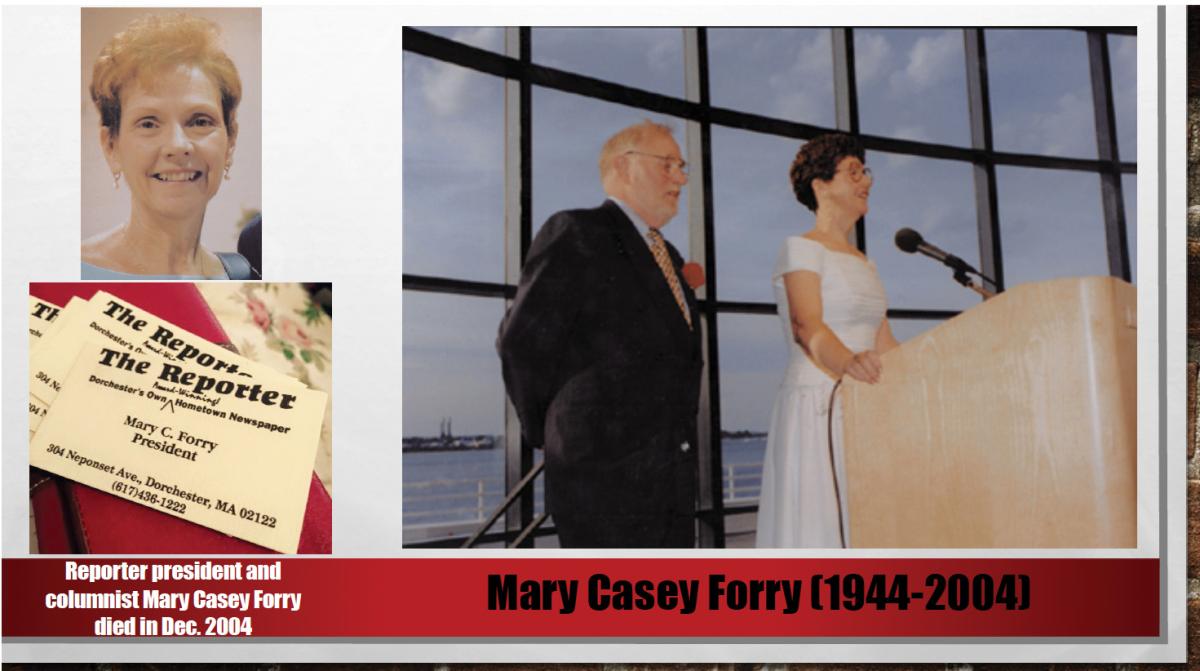

One was Mary Casey Forry, who had a wry eye and playful pen. Like Robert Benchley, she had the charming ability to make the mundane comical. “Dear Santa,” began a column. “Yep, it’s me again, and I’m hoping for a mink coat, but I’ll settle for another potholder.”

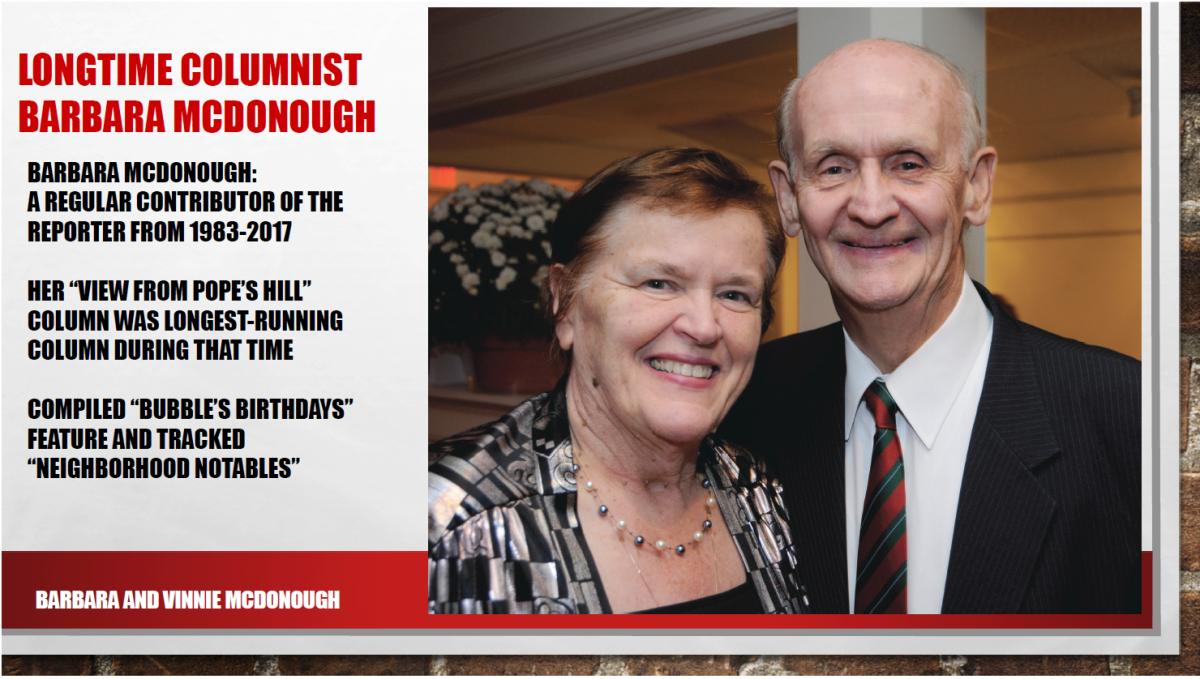

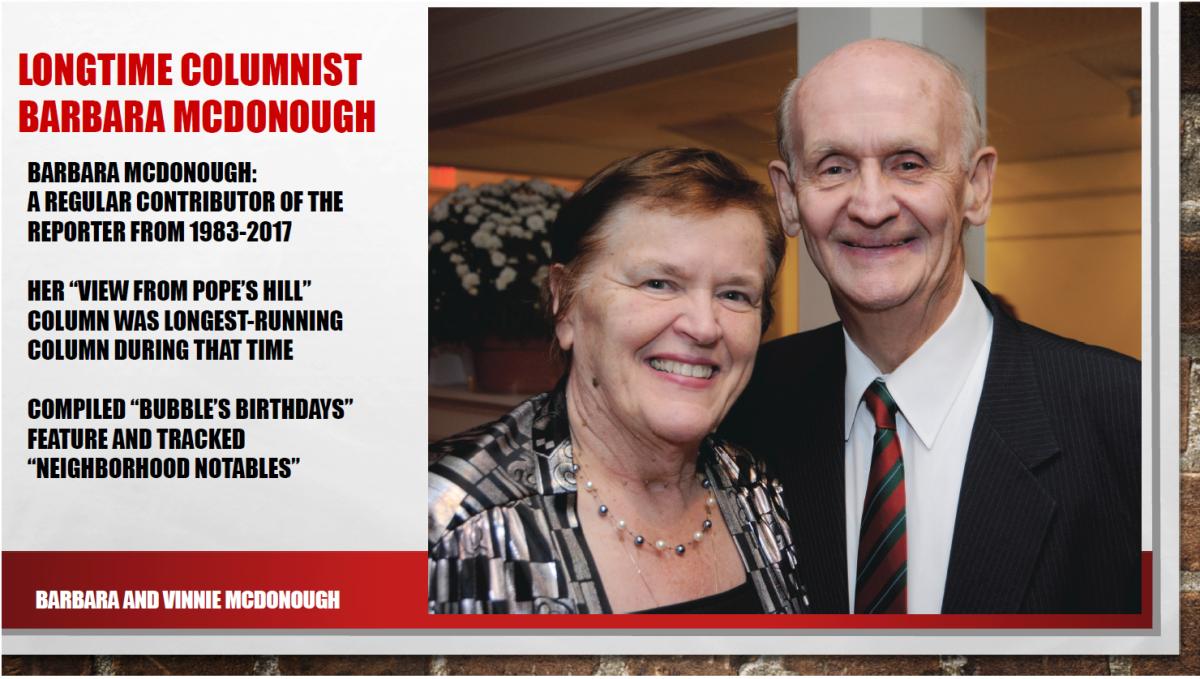

The other was Barbara McDonough, who has been writing a column of neighborhood news for a quarter century, and taking readers along with her to the Quigleys’ lawn party and to the Old Colony Yacht Club for Ruth George’s bridal shower, and who else would remind them of Nancy and Harry Harrington’s 25th anniversary, or alert them that Ann Connell’s nine years of work for the neighborhood association had won her a Dorchester mug.

There are features about mayoral candidate Finnegan’s tee shirts -- “Begin Again With Finnegan” -- about the neighbor whose job was painting flagpoles, and for nostalgia buffs, there were droll quizzes about life in Dorchester in generations past -- Who was Arnie (Woo-Woo) Ginsburg? (Radio DJ). Who was Jack Kennedy’s successor in the Senate? (Ben Smith). Who was the original owner of Channel 38? (The Roman Catholic Church).

The ads tell a story, too. Cedar Grove Cemetery boasted that it was “close to home.” An ad ballyhooed the cordless telephone as “that exciting new device that lets you talk on the phone and weed in the garden at the same time.” Lower prices catch the eye: At Rotary Liquors on Freeport Street, a six pack of Blatz was $6.99. At George’s Market on Neponset Avenue, sirloin tips were $2.79 a pound, and for $6,000, Columbia Pontiac would put you behind the wheel of a two-year-old Plymouth with stereo radio, extra clean.

After four issues, profit margins were such that the Forrys realized their dream was going to work, and they were ecstatic that an idea cooked up in their summer of dismay had, by Christmas, materialized into a product people would buy and use as an advertising forum.

Weekly readership for the Dorchester Reporter is 25,000. The web site, Dotnews.com has drawn as many as 100,000 hits a month, and on average, 800 digitial copies of the newspaper is downloaded each a week. For the Dorchester Reporter, Forry estimates a combined readership, paper and website, of 35,000 a week.

A Desk in the Back of Gerard’s

Establishing The Reporter in those early days demanded a punishing schedule, long days, weekend work, nights spent covering meetings and mornings selling ads -- 10 cold calls a day, 50 a week. After the cold calls, Forry would retreat to Gerard’s, a restaurant in Adams Village, and at a table in back each afternoon, he’d drink a coffee with Gerard Adomunes, review sales, and write stories.

As the years passed, The Reporter slowly built a loyal readership and burrowed into the soul of Dorchester so that today, for many people, it’s an indispensable tie to the neighborhood. It’s more than a newspaper, says Ellen Hume, founder of the Center for Media and Society at UMass. “The Forrys are the conscience of Dorchester.”

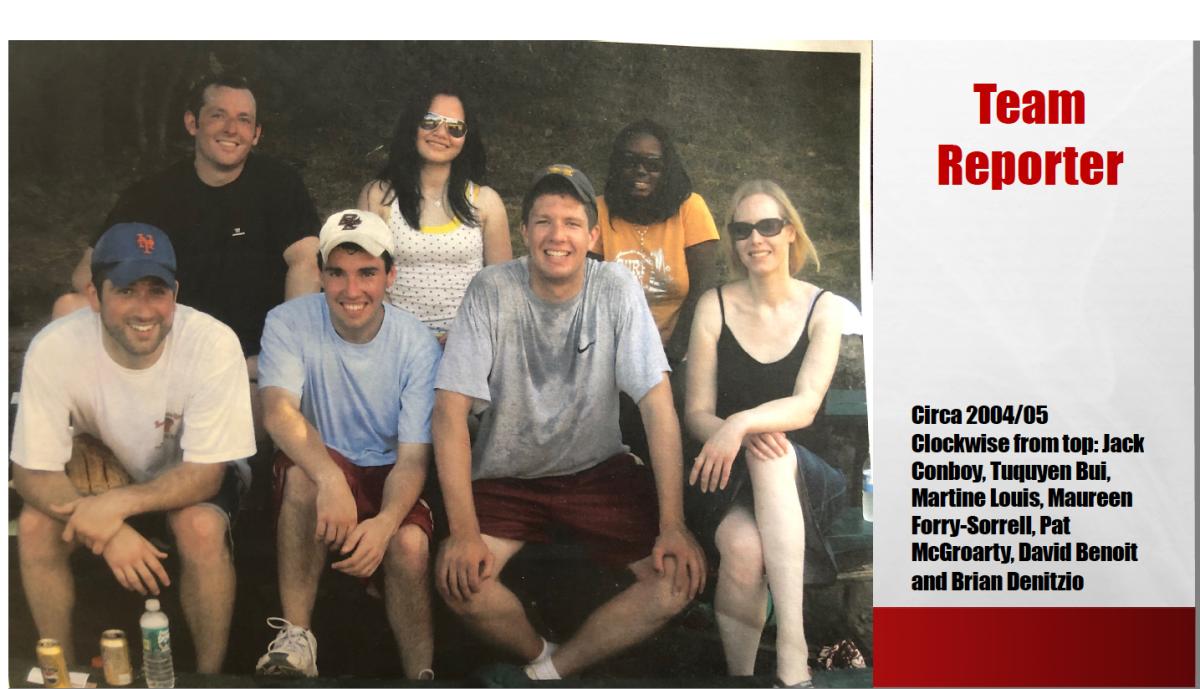

As metropolitan dailies are shrinking in circulation and influence, neighborhood papers have shown a resilience, and in the case of The Reporter, says former news editor Brian Denitzio, whose next stop was teaching at a middle school in Hyde Park: “It’s because it’s local, family-owned, and accountable to readers, not stockholders.

“The Forrys have a respect for readers that’s lacking at larger papers, and they live in the neighborhood,” he says. “They run into the people they write about, at the grocery store and at Dunkin’ Donuts, and so there’s no cheap ‘gotcha’ journalism. And they insist that reporters take time to report accurately and to ask tough questions — all of that is rooted in respect for readers.”

From the beginning, The Reporter has been a resource for chronicling the Dorchester of yesterday as well as today, and readers have submitted personal accounts recalling such events as the parade of Gen. Douglas MacArthur along Neponset Avenue in the 1950s. Readers have written about their memories of burgers at the Purple Cow on Gallivan Boulevard, and the starry ceiling at the Oriental Theater on Blue Hill Avenue, and the organ music at Sholes Rollerdrome at Neponset Circle, followed by late night coffee at the Englewood diner in Peabody Square.

Local ownership has its challenges, though, and for Forry, one has been the dilemma of editorializing during political campaigns when all candidates are close friends.

“There’s a distinction I make,” he says. “In the race between Jim Brett and Tom Menino, for example, both were and still are my friends. We didn’t endorse Jim, but I did write an editorial saying that I would be voting for him. This wasn’t an editorial that told readers how to vote. What I did was tell readers about the candidate for whom I was voting and my reasons.

“The other thing we did early on is this -- we sign our editorials. We have a name at the bottom. You read some of the Globe editorials over the years and you say, which fool wrote this one? I like names on editorials. If it’s got to be anonymous, I’m not interested.”

What gives community newspapers an edge over their larger, metropolitan siblings is that tether to the community and to the day-to-day concerns of readers.

“People trust the paper and its voice,” says Susan Asci, a former editor at The Reporter. “The community entrusts the paper with telling its story every week, and in many ways it’s a partnership. I don’t think people feel this way about daily newspapers.”

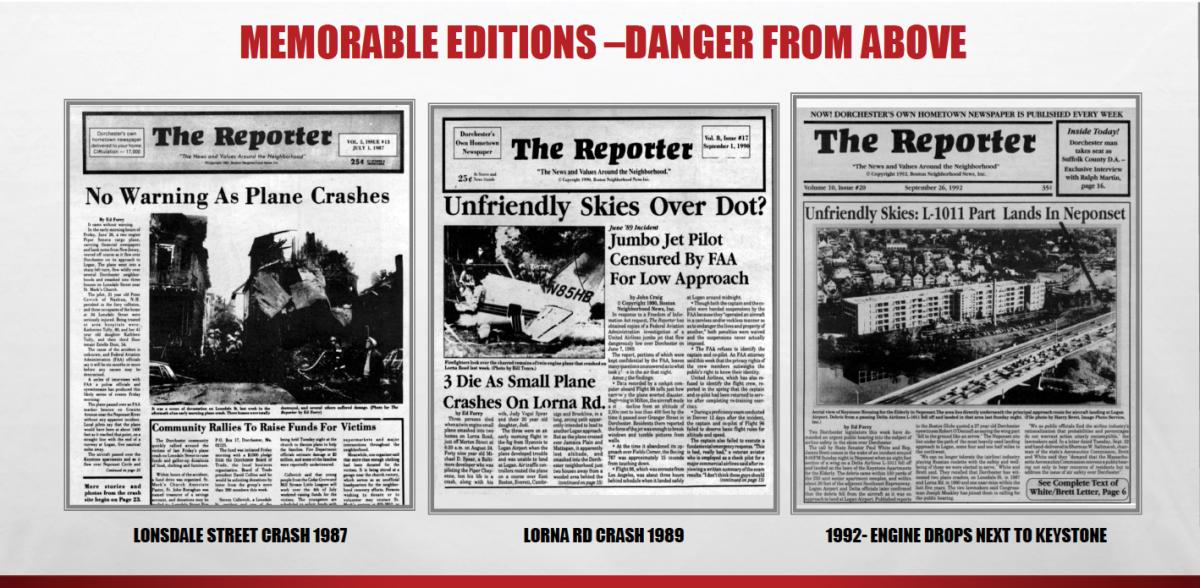

Through the years, The Reporter has distinguished itself in covering a number of major stories, in particular two plane crashes in Dorchester.

“There are hundreds of stories of advocacy in The Reporter’s files,” says Asci. “I recall in the late 1980s, early 1990s that Ed worked on pushing for information from the FAA and did a series of articles about low flying planes over the community. At one point, airplane parts fell on the lawn of the Keystone building and a small plane crashed in the community. Ed’s work forced the FAA to “amend flight routes over Dorchester.”

The Reporter has set higher standards for community journalism, says Bill Walczak, a co-founder and former director of the Codman Square Health Center.

“Before The Reporter, the community newspaper was mainly newsprint for ads, and you would never expect hard hitting news, controversial editorials, or smart news stories that The Reporter can legitimately complain are being raided by the Globe. I’m astonished at data dug up by The Reporter about shady real estate transactions, out of state buyers, and mortgage companies. And editorials on controversial topics are not what you expect in a newspaper that depends on ad revenue. What the Forrys have done is create the best community newspaper in Massachusetts.”

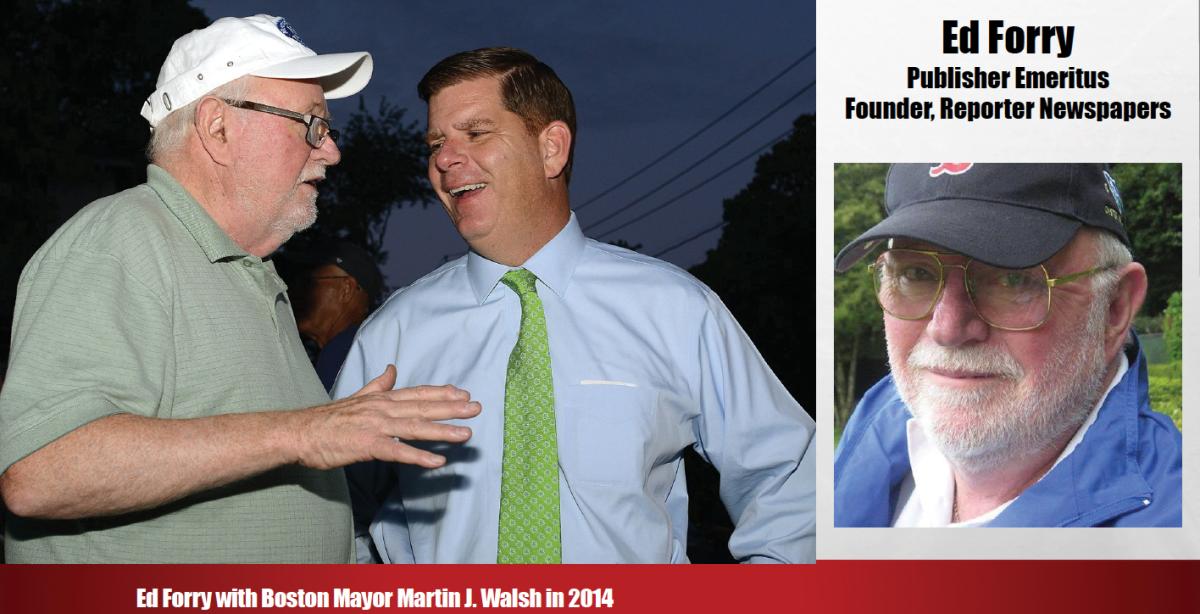

Paul LaCamera, who had advised Forry in 1983 to forget about starting a newspaper and to beg the bank for the chance return to his old job, laughs today to admit how wrong he was. “Fortunately, Ed ignored my advice, but at that time, at that age, starting a newspaper was reckless and irresponsible and also courageous. Look at the paper today. The reporting is terrific, and Ed’s editorials are the best in the city.”

In dozens of interviews, readers lauded the editorial page for its boldness, clarity, and the all important element of surprise. One issue might speak in behalf of controversial Senate President William Bulger, and the next would whack Herald columnist Howie Carr as a smart aleck.

Without exception, the editorial voice speaks on behalf of Dorchester. An example, says Jim Hunt, president of the Massachusetts League of Community Health Centers, is the newspaper’s role in the viability of Caritas Carney Hospital. “The Reporter’s leadership is at least partially responsible for Caritas Christi deciding not to close,” he says. “Without The Reporter, the epitaph of Carney might already have been written.”

Community journalism is hard work, and it lacks the notoriety and glamor of the big city dailies. Late nights covering meetings about hazardous waste in Port Norfolk do not rise to the drama of “Citizen Kane,” nor does a tip about four skunks at Tolman St. and Neponset Ave. rise to the humor of “Front Page.”

The Globe once described the Ashmont Grille as located in a “gritty” part of town, recalls Ferriabough, and The Reporter leaped all over the Globe for that. “First, Ashmont is an area where people aspire to live. It’s hardly ‘gritty,’ and second, the Globe reporter may have meant well, but who wants to take a chance going to a restaurant in a gritty area? The Globe could have hurt the restaurant enormously. The Reporter, by contrast, knows the nuances of the community.”

The Next Generation Settles In

After a 22-month battle with cancer, Mary Forry died in December, 2004, and, unable to let her go, Ed still lists her on the masthead as publisher. He retains the title of associate publisher, and the managing editor’s post is filled by their son, Bill, who is married to Linda Dorcena Forry, a Haitian-American who won election to the state House of Representatives in 2005. [She later won election to the State Senate and held the seat until 2018.]

When Mary was first diagnosed, daughter Maureen, 30, put aside a promising career in hotel management to stay by her mother’s side during her illness. Last year, her father finally persuaded her to join the family business, and she also has led the family in establishing the Mary Casey Forry Foundation, a non-profit organization with a goal to establish a local residential hospice program in memory of her mother and the compassionate care she received from the Caritas Good Samaritan Hospice at her life’s end.

As a senior editor at The Reporter and, at the same time, married to a woman running for political office, Bill faced an ethical dilemma in 2005 similar to what his father had faced a generation earlier, on his first day as a newspaperman, when he encountered his friend and mayoral candidate, Larry DiCara.

The way Bill Forry handled his crisis, says Hume, was a model of ethics that ought to be written about in a journalism review.

“He was trying to avoid steering the paper in his wife’s favor, as many hometown papers would do,” says Hume. “So, Bill gave up covering the political race, his life blood as a journalist, and The Reporter hired an ombudsman to monitor the political coverage [done by several young and capable reporters just out of college] throughout the campaign. That personal sacrifice in order to be fair and ethical is a hallmark of the Forry family, and why Bill is one of my heroes.”

Some Dorchester residents, still bruised by racial tensions of the past, see a symbol of progress in the marriage and public profile of Linda and Bill, black and white, Haitian and Irish.

“It’s interesting,” says Walczak. “We have the same publisher for the Boston Irish Reporter and the Boston Haitian Reporter. When I tell people, they have a puzzled look.”

Some readers praise Forry for making The Reporter a voice for racial harmony, but say that under the editorship of his son, the newspaper has become even more sensitive about racial issues. Forry, by the way, agrees. “Bill is his father’s son, but his own man, too,” says Ferriabough. “He has such an understanding of the Black community that sometimes I forget I’m talking to a white guy. That his wife is Haitian-American and his children bi-racial — that gives him a unique perspective. He has a personal investment in seeing Dorchester work for his family and for all families.”

She recalled a conversation years ago that convinced her of his commitment.

“I was explaining the difference between Black and white Dorchester,” she says, “and Bill took umbrage. I said Black Dorchester was North Dorchester and white Dorchester was Cedar Grove, basically — that’s how I grew up, a generation before him. He said, well some of us are working for it to be one Dorchester, and the more folk talk about divisions, the harder it will be to change ... He is so smart and intuitive and sensitive. I didn’t know at the time he was dating a Haitian-American woman.”

A number of readers expressed admiration that The Reporter serves as a breastplate of sorts, protecting Dorchester against richer communities that sometimes use Dorchester as a punching bag. As The Reporter sniffed in one issue, “Pity our suburban neighbors to the South, who have suffered for almost three years with highway construction in Braintree ... For us, we can take comfort in the knowledge that we choose to live close to downtown, just a 15-minute, 60-cent ride on a T train (when it’s working right.)”

HYPER-LOCAL is the Name of the Game

In his office on Mt. Vernon Street at Columbia Point, sitting at an eight-foot-long table where the staff holds editorial conferences over lunch, Forry is surrounded by bookcases busy with memorabilia that reflect his passion for family, first, and then, in no particular order, for Dorchester, Ireland, politics, former House Speaker John McCormack, journalism, Sen. Edward Kennedy, Dorchester pottery, and the Red Sox, his favorite team since that black day in 1953 when the Boston Braves absconded to Milwaukee.

With pride and a smile, Forry is confessing how provincial he is.

“My friend Paul LaCamera of WBUR told me that I am the most parochial person he knows, and I thanked him, because that was the nicest thing he could say. When it comes to Dorchester, I am parochial. But growing up, we didn’t think of ourselves as being from Dorchester. We thought of ourselves as being from Codman Hill or St. Gregory’s or Lower Mills. There’s an architect from Port Norfolk, J. Edward Roach, who came up with the concept of the villages of Dorchester, and he’s right. We were all from villages within Dorchester, and it was a wonderful, very simple place to grow up. I still can’t forget the smell of chocolate from Walter Baker in Lower Mills. Whenever there was a southeast wind, the aroma of chocolate swept our neighborhood, and my mother would say, if you smell chocolate, it’s going to rain.”

A man of modest mien, Forry does not fit the Hollywood image of a newspaperman. He never had a paper route, never hustled as a copy boy and never worked for a big city newspaper, although he had one unusual experience that helped prepare him to publish a newspaper.

“I was a mailman for four years,” he says, pridefully. “While I was at BC, I delivered mail, at one point or another, on 85 percent of the streets of Dorchester. Much of it was in what we call Dorchester Center, which is the old 02124 district, and that covers the river end of Dorchester up through Lower Mills, from the Keystone Building along the river to Gallivan Boulevard, over Codman Hill and Codman Square to near Hemenway Park, Lonsdale Street, and, in the other direction, to Mattapan State Hospital and a little bit of Blue Hill Avenue. All those streets, over and over and over, I walked ‘em.”

Forry laughs at the suggestion that he has been transmogrified into a sage of all matters Dorchester. As Hume recalls: “When my husband became head of the Kennedy Library Foundation in 2001, it was Ed Forry he turned to first to show him what Dorchester and Boston are all about. Then it was my turn. When I was founding the Center on Media and Society, and in 2007, when we launched the New England Ethnic Newswire, Bill was the smartest adviser I could have hoped to engage.”

Proud Alumni Weigh In

It is lore in the newspaper business that interns, copy boys, and cub reporters trade nightmarish stories about the lunacy of their early days working for the city desk, and yet many former interns describe their tenure at The Reporter as an honor, an experience of which they’re proud, and they credit the Forrys.

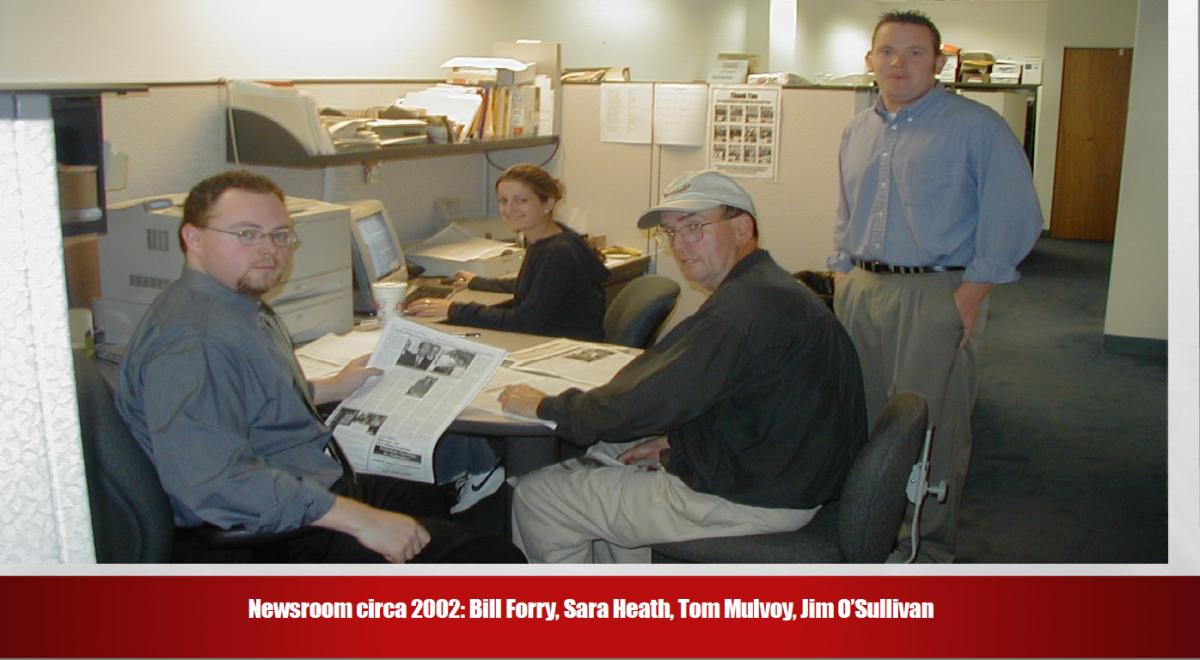

A scene in the Reporter newsroom circa 2014 or 2015. From left: Ed Forry, Gin Dumcius, Lauren Dezenski, Barbara Langis. Bill Forry photo

Whether at a metropolitan daily or small community newspaper, the early days are heady for copy boys and copy girls, interns and cub reporters. When Lou Manzo arrived at The Reporter for his first day of work at a newspaper, Bill Forry sent him right back out the door. “Go look for a story,” Forry said. “Drive around Dorchester. Get lost.”

Manzo recalls that a few months later, he had wrapped up a story and was awaiting only a call from Mayor Menino for a quotation. To while away the time, he was playing basketball at Boston College, when his cell phone rang. He left the court, wrote down Menino’s response, then returned to the game. “Who was that?” asked a player, and displaying all the nonchalance he could muster, Manzo said, “That was Mayor Menino.”

McGroarty was a junior at Boston College when he reported for his first day at The Reporter, June 5, 2005. He tagged along with news editor Jim O’Sullivan to St. Mark’s Parish to check out a tip about abandoned Stop & Shop carts. “As we purred down Morrissey Boulevard in Jim’s Mustang convertible, “McGroarty recalls from his office in Berlin, “I remember thinking that the Forrys must compensate their people pretty well.

“We found the shopping carts, which Jim photographed, and later, he posted the photos online as a breaking news item -- Fridays are slow. We also found a young woman and her son nearby, creating quite a commotion. She noticed Jim crouching in the road to snap pictures of the offending carts, and after he revealed himself as a reporter she spent 15 minutes trying to convince him that she was the victim of serious identity theft. She waved a stack of receipts and bills in his face while I entertained her knee-high son, who responded to my small-talk by loading a cap gun and play-assassinating me.”

Gutting It Out in Rough Sailing

Journalism in general, and at the community level in particular, with its long hours and relentless pressures, takes a toll on family life, and the Forrys have paid a price.

“It’s true that over time, we failed to take vacations or extra time for family,” says Ed, “and it was to our detriment. A weekly paper is a grind, inexorable, wave after wave, and it can be so mesmerizing that it becomes detrimental. It stops you from thinking. I discovered that if I didn’t take time away, even for a day -- if I didn’t take a day and not do something for the paper, I’d begin to lose perspective. Now, having said that, I didn’t take enough time, and there’s a cost in terms of family.”

His journey ran into rough sailing in the economic storms of the early 1990s, and The Reporter nearly sank. Much of what ordinarily would be considered profit at a community newspaper had been reinvested at The Reporter in writers and editors. By 1993, however, the economy had become so anemic that the Forrys were paying the staff, but taking no salary themselves. After examining the books, a banker said there were two options -- lay off all employees or simply go out of business, because there was no way to survive.

The old fears returned.

“I was closing in on 50, and if you have a mom-and-pop operation, you’re concerned with making enough money to get through the month, and if you make it, you take a breath, and say, okay, what about next month? It was a Damoclean moment, because you say to yourself — if I think too hard about this, I’ll pull the plug because the pressure’s so great.”

The staff was reduced drastically, and Forry’s workload increased dramatically and detrimentally. The crisis strained the family, and Forry believes the paper might not have survived without Mary’s steadfastness and — it might be added — his allegiance to The Reporter.

“His love of journalism is contagious,” says Chris Lovett, who edited the Argus-Citizen in the 1970s and served news director of the Neighborhood Network News, BNN-TV. [Lovett retired from NNN in 2021 and is now a contributor to the Dorchester Reporter]. “But what I admire about Ed and Bill goes beyond journalism. When the paper started, Ed and Mary were defying odds. Given population changes, the migration of readers to television, and the demise of the old advertising base in the neighborhood commercial centers, I thought the future of The Reporter, like many other neighborhood papers, was shaky. But they’ve done a good job keeping up with change. A good deal of this is Dorchester itself, which has a seemingly inexhaustible ability to renew and reinvent itself — or combine new and old in different chemistries, despite all the adversity.”

Through her writing as well as her counsel, Mary was so involved in The Reporter that four years after her death, her spirit permeates the newspaper. In preparing for this special issue, Forry has reviewed many editions and read again many of her columns. “I’d forgotten her crabgrass piece,” he says, wistfully. “It was hilarious.”

So interlaced is she in him that he sometimes refers to her in the present, and so difficult is it to acknowledge her passing that he has been unable to watch video of her or listen to her voice on audio tapes. “When she died, there was a period when I tried to think of her, and couldn’t remember her voice,” he says, puzzled and talking more slowly than usual. “I couldn’t bring it to mind. It came to me after a few months, but it must be a part of the way you deal with these things. Every time I round a corner, I run into another wall I didn’t expect that reminds me of her. It’s not a catastrophe, not a train wreck or anything like that, but it is a collision.”

An example occurred a few weeks ago when, from a shelf in a closet, he retrieved folders with items that remind him of her, and he left them accessible for later viewing, Included was a photograph of her at his 60th birthday party a few months before her death. “I have a birthday cake in front of me. She’d lost her hair at that point, and so she had a bandana on, but she looks great, and she has a great smile,” he says. “It’s a great memory.”

Helping People Meet People

The first years of the Reporter’s have been a turbulent time for Dorchester, one of growing immigration and migrating ethnic populations, but The Reporter has remained committed to Dorchester’s multiformity and heterogeneity. “I feel strongly about this,” says Forry. “Dorchester begins with a D, and that’s for diversity. The more we bring people together in a common place, that is, the newspaper, where they can read about one another and become more of a family with each other -- I didn’t do such a great job at that. Bill’s done a better job at bringing diverse voices together. But it’s the concept -- we’re out to create an environment where people will get to know one another.”

Some readers expressed gratitude for The Reporter’s role in supporting Dorchester’s cultural institutions. “I love The Reporter,” says Joyce Linehan, president of Ashmont Media and an activist in Dorchester’s arts community. “Its coverage of community issues is well-written and well-researched, and it brings a degree of historical memory most other papers don’t have.”

That historical perspective is evident in the newspaper’s editorial policy, in particular in Forry’s anger that the government sliced through Dorchester in the 1950s with an expressway to the South Shore that isolated Dorchester people from Dorchester beaches.

“We stopped being a seaside community,” he says. “Except for Port Norfolk and Precinct 10 in Savin Hill, the expressway cut Dorchester off from its beaches. The generation that grew up in the 70s never uses our beaches. Imagine if they tried putting a six-lane highway through Marblehead or across Falmouth Heights.

“That’s what they did to us in the Fifties, and we let it happen because people weren’t made aware that Dorchester was being compartmentalized for the convenience of other towns. Ironically, the expressway led to development of towns to the south, which made it easier for people to move from Dorchester to the South Shore.”

Through the years, The Reporter railed against what it sees as subtle racism in the use of “North Dorchester” to identify the section close to Roxbury, which had more of a minority population, more poverty and more crime. “We’ve written about it, and Bill has gone beyond where I went with it,” says Forry. “It happened in the 50s when someone in the Boston Redevelopment Authority introduced the designation of North Dorchester to identify the neighborhood where more blacks live, and then it drifted into common usage. But we think it’s racist and we forbid use of it in the newspaper.”

Ivory Tower Moments

In 2008, Bill Forry was home with his two children one recent morning, while his wife, the legislator, was at a conference in China. At dawn, a body was discovered at a park on Adams Street near Pope’s Hill, and Bill called his father. “I’m taking care of the baby. Can you swing by the murder scene and take a picture? he asked. “Sure,” said Ed. Then Bill grunted. “What’s the matter?” asked his father. “The baby just vomited.”

As a boy on the hardscrabble streets of Dorchester, Bill was given no concession because his father edited the local newspaper.

“I hung out at Walsh Park, drinking beer, doing what teenagers do,” recalls Bill, “and one day we were heading to Dorchester Park, when one kid started to get all over me because my father had written an editorial that said the city ought to clean up Dorchester Park and get kids to stop drinking there. They got on me for that, as if it was my fault for having a dad who would write that. At the time, I empathized with the kid. Today, I empathize with my father.”

He was challenged about it in class, too.

“I had teachers who gave me a hard time, one in particular, because I wore a Dorchester shirt with a shamrock. The teacher was originally from Dorchester, and it didn’t resonate with me, but he said that Dorchester was not just about shamrocks, that Dorchester is a much larger place. He said that you guys are putting out the newspaper and should know better. I was defensive. I thought he was an ass, but I now agree with him, although I respect everybody’s right to identify with Dorchester the way they want, which he didn’t do.”

If there was a romance to reporting, it was not clear to Bill the day when he was a teenager and an elderly woman from Ashmont Street called, furious that her weekly Reporter had been tossed on the porch in a way that broke a window on her storm door. Bill and his father rushed to Ashmont Street to sweep the glass. It’s hard to imagine the esteemed Taylor family, former publishers of the Globe, hustling to Ashmont Street to sweep up glass, but as Bill Forry says, “There are no ivory tower moments for us.”

In high school and college, he dabbled in campus newspapers, and in 1992, at age 19, he was hired by NBC to work at national political conventions in New York and Houston. That led to an internship at WCVB-TV, Channel 5, but it was a violent time in Boston, and knowing what he knew about Dorchester, he saw a superficiality in television news. “Coverage was driven by police scanners and ambulances. I didn’t see the thoughtful side. It was, you know, make sure we have a truck at Franklin Park to get tonight’s shooting.”

The experience left him with a greater appreciation of what his father had achieved with The Reporter, and after an interlude with a state agency, where he bristled at the bureaucracy, he accepted his father’s offer of a job as news editor. Since then, he has spurned work at metropolitan papers, preferring the intimacy of community journalism.

“I don’t know how the Globe operates,” he says, “but here, if the telephone rings, you answer it. If someone walks in with a legal notice, you deal with that, so it’s not as though you can focus on one thing and expect to be able to do that on any given day. I don’t sell ads, but if someone walks in the door with an ad and there’s nobody else around, for whatever reason, I have to deal with that person. That’s a difference between a big operation and ours.”

With a wife and [four] children, he works half as many hours as he did when he was single, although life at the office remains as unpredictable, day to day, as ever.

“You always had to be prepared for visitors,” says Asci. “Former Mayor Ray Flynn would stop by for coffee and a chat. On several occasions, former Congressman Joe Kennedy stopped by to meet with us. And international leaders do, too. Nobel Peace Prize recipient John Hume dropped in one day to give us an exclusive interview on the Good Friday agreement in Ireland.”

Although the future of print journalism is uncertain, community newspapers are thought to have an advantage over metropolitan dailies. “The Reporter has a bright future, because it provides a unique service,” says Ellen Hume. “It needs to beef up its web and take advantage of participatory features. I think it should feature an interactive map showing not just the ‘bad’ news, but the history and events that people could contribute to jointly. It can list more resources about Dorchester and migrate from the two-dimensionality of a newspaper to the multi-dimensionality of an interactive website.”

Not everyone is as optimistic.

“I don’t have much hope for the future of newspapers,” says Manzo. “I love them, but I would never buy one. Maybe that is an indication of my poverty, but I think it has more to do with how people receive information. I’m used to seeing it on screen, as are my peers. Community newspapers will survive, though, as long as there are pizza shops. When I go into a pizza place, I grab whatever free newspapers I see. That’s a tradition that will remain.”

At the same time, he says, community journalism is an imperative. “A nation is bound through sub-communities, and community newspapers are their binding force. The Globe is not going to cover South End Little League, but for some families, these stories matter more than the Red Sox. The Globe is not going to cover the complaints of an old lady railing for a stop sign at a busy intersection, but maybe her complaint, given proper voice in a community newspaper, will save a life and, on that level, a seemingly insignificant story is of more importance than reporting how much Obama raised last month.”

Some people shudder at the notion of Dorchester without The Reporter and all that it symbolizes. As Ellen Hume says, “I could get sappy about how the Forrys represent the American dream — starting your own community paper, building it into four papers, and then Bill marrying Haitian-American Linda to bring together two cultures that make America great. Who could have imagined, during the busing crisis, that Dorchester would provide an ideal example of a mixed-race power couple? Bill and Linda are what give me hope for our city and our country.”

Jack Thomas, a native of Port Norfolk, was a reporter, columnist, and editor at The Boston Globe for more than 40 years. Jack died in 2022 after a long, brave battle with cancer.