May 17, 2023

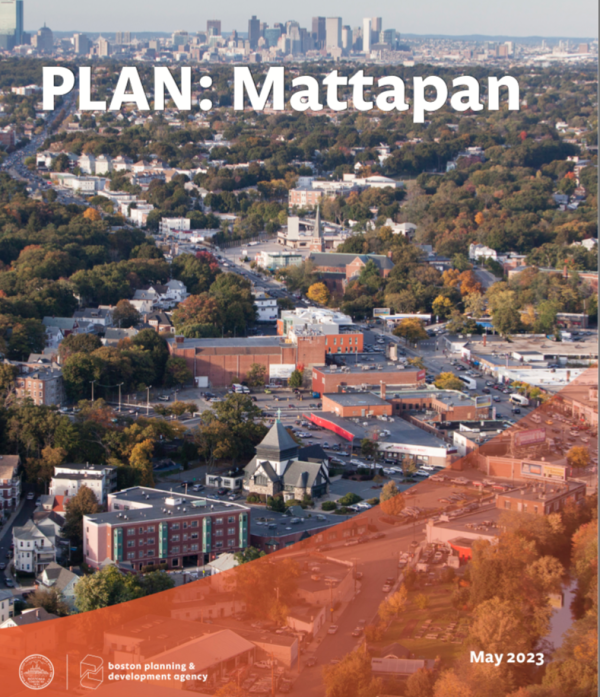

PLAN: Mattapan, a five-year neighborhood development effort that calls for additional dwelling units in backyards and re-zoning Mattapan Square to allow for more mixed-use development, last week received the approval of the board of the Boston Planning and Development Agency (BPDA).

The plan aims at creating generational wealth in an area whose residents are 68 percent Black or African American, and transform it into a neighborhood where retail, parks, and transit are a 10-minute walk from every Mattapan resident’s home.

But PLAN: Mattapan may also be among the last of its kind, as city officials say they’re shifting away from that style of planning and attempting to remake the way developers and residents interact with City Hall. Mayor Michelle Wu last year picked as her chief of planning, and BPDA director, Arthur Jemison, a federal housing official who had moved back to his former Ashmont neighborhood.

“We need more predictability, we need a clear sense of what the rules are, so it’s not a frustrating, counterproductive, and exhausting process to see how your neighborhood grows, and we also need to incorporate standards for affordability and transportation access and all of the other quality of life needs that the development process is supposed to really deliver for communities,” Wu told Reporter editors in a sit-down inside City Hall last week, days before the BPDA vote on Mattapan.

The neighborhood-by-neighborhood planning process is “not the best vehicle” to get to that point, she said. “To get a neighborhood planning process right takes two to five to seven years, depending on which neighborhood you’re talking about. And it’s at a scale where by the time you’re done with that neighborhood, multiple things have shifted, and, in fact, you’ll never get back around to the entire city being comprehensively connected.”

That means taking the existing neighborhood planning processes launched in recent years – aside from Mattapan, which just wrapped up, Newmarket, East Boston, Downtown, and Charlestown are underway – and letting them finish. Wu noted that they kicked off in response to people in those communities, as residents said the process by which developers were asking for variances to build out their proposals, was creating “uneven and chaotic, haphazard results for our neighborhoods.”

Those efforts will be finalized on different timetables as the Wu administration strives to shift planning and overhaul the BPDA. Wu recently hired Katharine Lusk, a former adviser to the late Mayor Thomas Menino, as executive director of the Planning Advisory Council, which she created through an executive order and tasked with creating a “central authority for initiating, reviewing, and implementing citywide planning.” The council includes various Wu cabinet officials, from housing, parks, and arts to transportation.

“That will help us establish a citywide but much more surgical approach to planning,” said Wu, “where we’ll focus on areas like squares and corridors, where there’s already need for foot traffic for small businesses to be supported and you start to see the impact of that redevelopment in adding some housing in places that make sense and meet communities’ needs, rather than one gigantic neighborhood at a time where everyone’s waiting their turn in perpetuity.”

Wu defined the goals as “a smaller scale but citywide open space planning, a citywide neighborhood design process, so that each neighborhood will have its individual and unique design aspects that will be required in the development process, in squares and corridors, so we can then codify this in zoning and set real rules.”

Organizational changes have also been underway. Planning staff at the BPDA had been spending 50 percent of their time reviewing developments, but the Wu administration has dedicated planning staff focusing on long-range plans, and “not getting pulled into every individual proposal that comes along.”

Wu said it can be difficult to make “hard and fast” rules for one area. “The size of neighborhoods is so different that Plan: Bay Village, for example, is very different than saying Plan: Dorchester,” she noted. “But by and large we’re moving away from the large-scale neighborhood planning processes because it’s not at the right scale of specificity or urgency for what is needed.

“I do hear very much from community members. Things are happening in the planning, some of it was interrupted from Covid, some of it just has been slower but the development has continued and continued and continued without that defined plan. So, we want to try to catch up as much as possible citywide.”

In the meantime, implementation of PLAN: Mattapan is underway. As part of their efforts to ease the ability of Mattapan homeowners to build accessory dwelling units (ADUs), city officials plan a parcel-level study that is expected to provide insight into the best ones that can house ADUs.

“This is not going to add significant time to the implementation,” Jemison told the Reporter.

The zoning changes for Mattapan are expected to come before the city’s zoning commission in the fourth quarter of this year, and city officials believe many of them will be in place by 2024.

As for Mattapan Square, Jemison said there is the potential for the area to see more development like the Loop, a new six-story building at the trolley station with 135 affordable units and a nonprofit grocery store chain in the first-floor commercial space.

“I think Mattapan Square has the chance to seize its position even more firmly as a growing mixed-use, mixed income square, a major destination in the city,” he said.