September 6, 2023

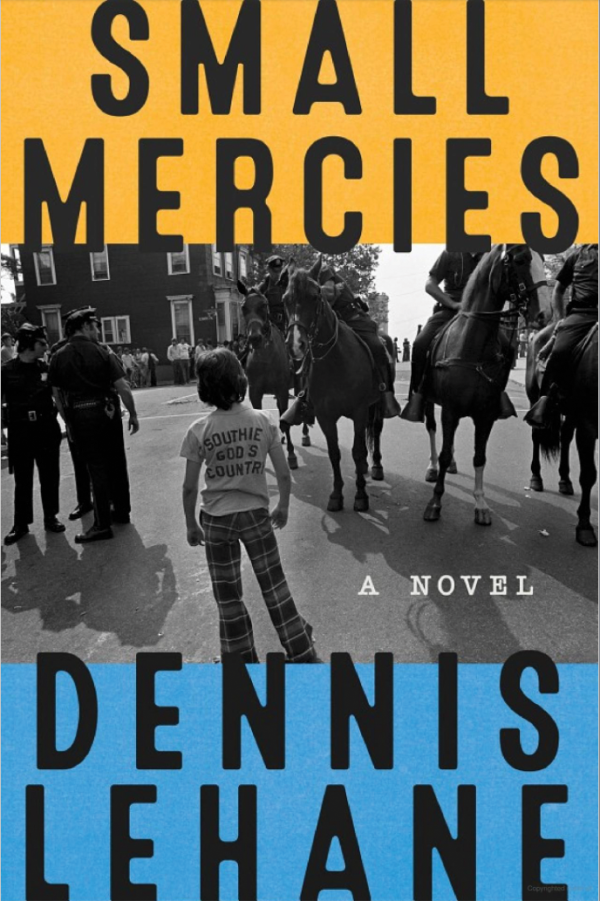

Dennis Lehane’s “Small Mercies” begins with a hint of dread: an electrical outage in the tenacious predawn heat of September 1974. The setting is South Boston, and the whole neighborhood is bracing for a collision.

With a daughter on the cusp of her senior year in high school, Mary Pat Fennessy expects to show up at a rally of white parents against the beginning of school desegregation. The ensuing explosion of racial antagonism would make national news and history, but the latest novel by the Dorchester native pivots on a single hate crime on the Red Line. It’s a fictional event that, disclaimers aside, has some features in common with two other hate crimes that took place along the Red Line a few years later. And, as with the fiction grounded in South Boston, the real events in Dorchester were, not just about crime, but a sense of duty to survivors and the dead.

In “Small Mercies,” a young Black man, Augustus “Augie” Williamson, is killed after being chased into Columbia Station (now JFK/UMass) and attacked by a group of young whites, including Mary Pat’s daughter “Jules.” The morning after, Mary Pat only knows that her daughter hasn’t come home. Her repeated attempts to find out what happened, and why, account for most of the book.

A 42-year-old public housing resident, Mary Pat is a twice-married a survivor who has already lost family members to violence and drugs. She opposes “forced busing” to any school outside her neighborhood, but even more so if the destination is predominantly Black.

That does not prevent a respectful, if distant, relationship with a Black co-worker, whose son turns out to be the man killed in the hate crime.

Mary Pat also resents people in the suburbs, who live beyond the reach of desegregation and have been less exposed to the military draft. If she feels inferior to them, that only stokes reactive flames of South Boston pride.

That’s of little help when she seeks information about her daughter from the people she trusts the most, South Boston’s gangster regime, which responds with stonewalling and silence. As her frustration turns combative, a gangster lieutenant who lives on Dorchester Heights reminds her that inequality begins closer to home. “Southie” might be Mary Pat’s hometown, but in the local autocracy, her place is the lower end.

By the time Mary Pat realizes that her daughter has been killed, the story of what happened at Columbia Station becomes more tangled and nuanced. A seemingly impulsive crime doubles as a twofold cover-up, with multiple victims and motives. This makes the attack on “Augie” Williamson quite different from what happened to William F. “Frankie” Atkinson in 1982.

What’s less imaginary in the novel is that conflicts of race and class can overlap, that people fanning the flames try to avoid the heat, and that people with better intentions can still be implicated.

Part of what’s suppressed in the cover-up is that Jules was also a victim of gangster violence and sexual exploitation. That’s sensational enough for a crime novel, but no worse than some of the real-life horrors taking place over a number of years in “Black Mass” and “All Souls,” the South Boston memoir by Michael Patrick MacDonald. Mary Pat learns of her daughter’s death, not by word of mouth, but by reading between the lines when a gang boss offers her money to go away—quietly. She answers with a cycle of retribution, her own version of “Southie won’t go.”

For all its violence, Mary Pat’s battle against the code of silence is less about revenge than it is about a reckoning: ultimately forcing South Boston’s apex predator to say her daughter’s name. Because the local regime tries to deny her right to bury her own dead, she responds like Antigone, survivor of a ruling family in the conflicted city of Thebes, who defies its worldly authorities after the violent death of her brother. As Martha C. Nussbaum explained the Greek tragedy in “The Fragility of Goodness,” “Duty to the family dead is the supreme law and the supreme passion.”

By combining larger story lines often treated separately – court-ordered desegregation and a ruthless gangster regime, Lehane follows Joseph Conrad’s novel “Under Western Eyes,” which is cited in the epigraph to “Small Mercies.” Conrad was writing about individual struggles with the mutually reinforced powers of tsarist autocracy and revolutionary terror in Russia. Their interplay created a traumatic cycle of fear, dissimulation, and silence, a cycle that Conrad breaks in a face-to-face reckoning with survivors. As his narrator puts it, “the real drama in autocracy is not played out in politics.”

•••

Boston’s history of racial conflict and inequality began long before 1974, with violent flare-ups continuing into the 1980s. In his recently published history, “Boston Before Busing,” Zebulon Vance Miletsky shows that school segregation goes back at least as far as 1798. After World War II, parent leaders organized to seek remedies, only to be stymied by elected leaders. There were also racial barriers in jobs and housing that, as Miletsky argues, made Boston just another part of the “Jim Crow North,” complete with more dangers after sundown.

While the federal government was enabling racial inequality in migration to the suburbs, projects creating the “New Boston” displaced people from several neighborhoods.

By the late 1960s, a program meant to remedy discrimination in mortgages accelerated the white exodus from parts of Dorchester and Mattapan, with hundreds of housing units abandoned or destroyed by fire. If the conflict over desegregation intensified turf antagonism, clashes continuing into the 1980s were also tied to poverty, public drinking, and a dearth of programs for young people.

As a longtime community organizer in Dorchester, Lew Finfer, recalled, “It was hard to keep together our integrated Dorchester Community Action Council in this period because of the strong feelings people had on desegregation with busing. But we found plenty of common issues on redlining, housing abandonment, over-assessment on property taxes, crime prevention so that whites and Blacks from Dorchester in our group could work together and get things done.”

In May 1980, youth troubles were already on the agenda at a meeting of the Columbia-Savin Hill Civic Association. The most alarming incident was the death of Michael Doherty almost two months earlier, after a group of white youths chased a Black man into Columbia Station. A 19-year-old white man from Dorchester’s Lower Mills, Doherty told the attackers to “knock it off.” Instead, they chased him all the way up to the Southeast Expressway, where he was killed in a hit-and-run crash. His body was found two days later, when it was spotted in a median strip by a driver caught in slow traffic.

It took three weeks before the attack was reported in the Boston Globe. Three days later, a Globe editorial hailed Doherty as a “hero for Boston,” but other forms of recognition would have to wait, even after three juveniles pleaded guilty to charges of manslaughter—without any requirement for jail time. When the chase took place, all three had already been on probation for previous offenses.

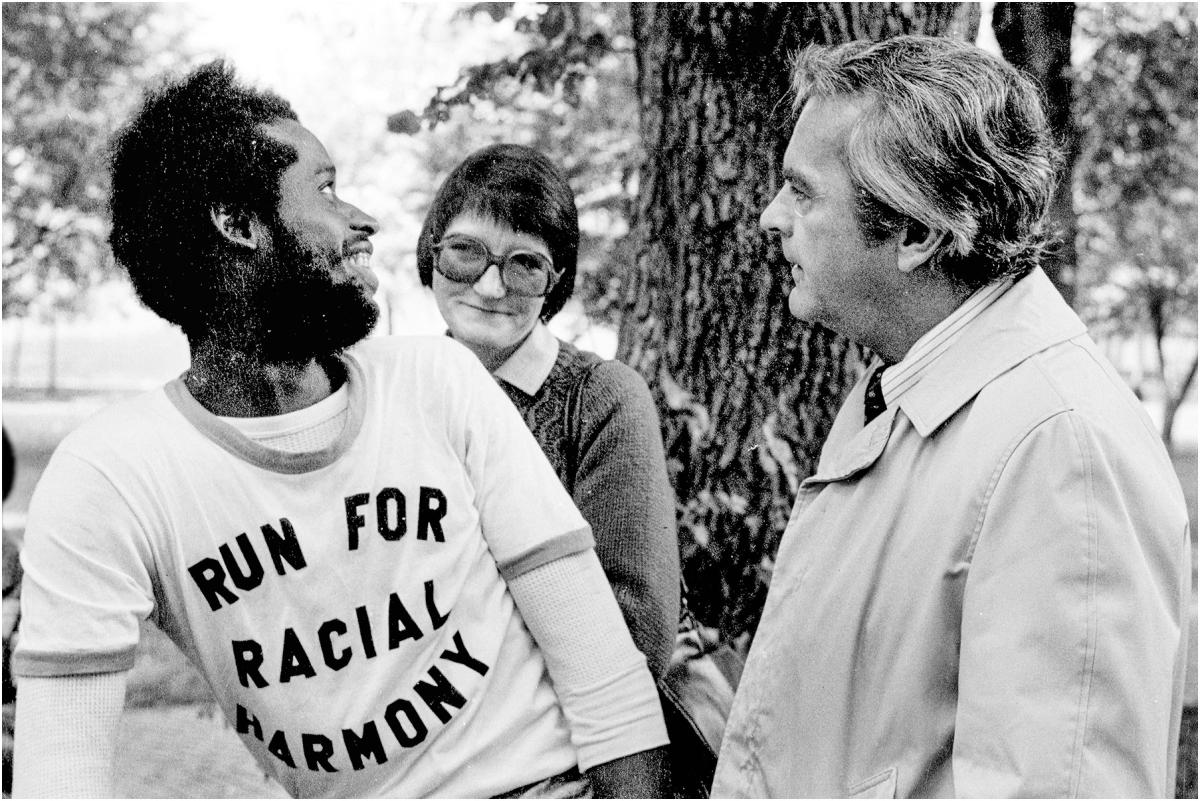

In early September, Doherty was honored at a dinner in Roxbury organized by a member of Twelfth Baptist Church. There would be even more attention given later that month to the “Run for Racial Harmony” by Ron Taylor, a 26-year-old Black man from Brattleboro, Vermont, who had previously lived in Boston. To help raise money for a scholarship fund in Doherty’s memory, he ran 130 miles, from Brattleboro to the Boston Common, and repeated the course the next year.

Another two months passed before Doherty was recognized in Dorchester, with a scholarship benefit at Florian Hall that raised almost $5,000. To the sounds of bagpipes and gospel hymns, a multi-racial turnout – with community activists, clergy, and elected officials –put the spotlight on heroism. As one of the organizers, Kathleen Kilgore Houton, said at the time, “Michael Doherty wasn’t just a victim. He sort of took an interventionist role and said, ‘This is the kind of thing people ought to do.’”

Five months earlier, Mayor Kevin H. White had named Frank N. Jones, a former civil rights lawyer, to head The Boston Committee. Its mission was to address underlying causes of racial violence and help people of different races meet common needs. That led to a diverse group of residents forming the Dorchester Task Force, which would later play a role in response to the next fatal act of racial violence along the Red Line.

•••

In March of 1982, William F. “Frankie” Atkinson, a 30-year-old Black man and father of three from Dorchester, and his white friend, William Grady, were chased by a group of white youths into Savin Hill Station. As in Lehane’s novel, the chase began after midnight, with a racial taunt by one of the attackers. Atkinson’s body was discovered later, near the tracks between Savin Hill and Fields Corner.

Five young people from the Savin Hill area were convicted of assault, with two of them also convicted of manslaughter. Defense attorneys tried to distance the attackers from the immediate cause of death—possibly the impact of a train. At the first trial in 1983, the prosecutor, John Kiernan, convinced a mostly white jury that Atkinson wouldn’t have even been on the track, if not for having been chased by a “racial posse.” But despite pleas from Black leaders and the Anti-Defamation League, Suffolk County District Attorney Newman Flanagan declined to press civil rights charges.

A few days after the incident, a number of Savin Hill residents who had gathered at a hastily called community meeting denounced the attack. The president of the Columbia-Savin Hill Civic Association at the time, Jim Canny, confessed to the gathering, “You know it’s the people who care in the community, who are most active in the community, who are the most shocked and who can do the least about it.”

Some of those who cared also reportedly faced pressure to keep silent from neighbors trying to protect the attackers.

Another member of the group recalled that some neighbors reacted to the attack by pointing to crimes against whites in predominantly Black areas, even referring to the alleged attackers as “our boys.” His conclusion: the racial turf sentiments so often ascribed to South Boston could also be found in other places.

That same week, people at another meeting, near Uphams Corner, were planning a community walk the following Sunday.

At the Savin Hill meeting, there was some disagreement, at least with the timing. As Canny argued, “It looks as if you’re blaming the Savin Hill community for something that happened throughout the city.”

Earlier in 1982, Barry Lawton had moved to Dorchester’s Meetinghouse Hill neighborhood, attracted by the panoramic view of Ronan Park and Dorchester Bay, but cognizant of racial tension.

Ron Taylor with Richard and Kathleen Doherty, the parents of Michael Doherty, at the conclusion of the 2nd “Run for Racial Harmony” at Boston Common in 1981. Chris Lovett photos

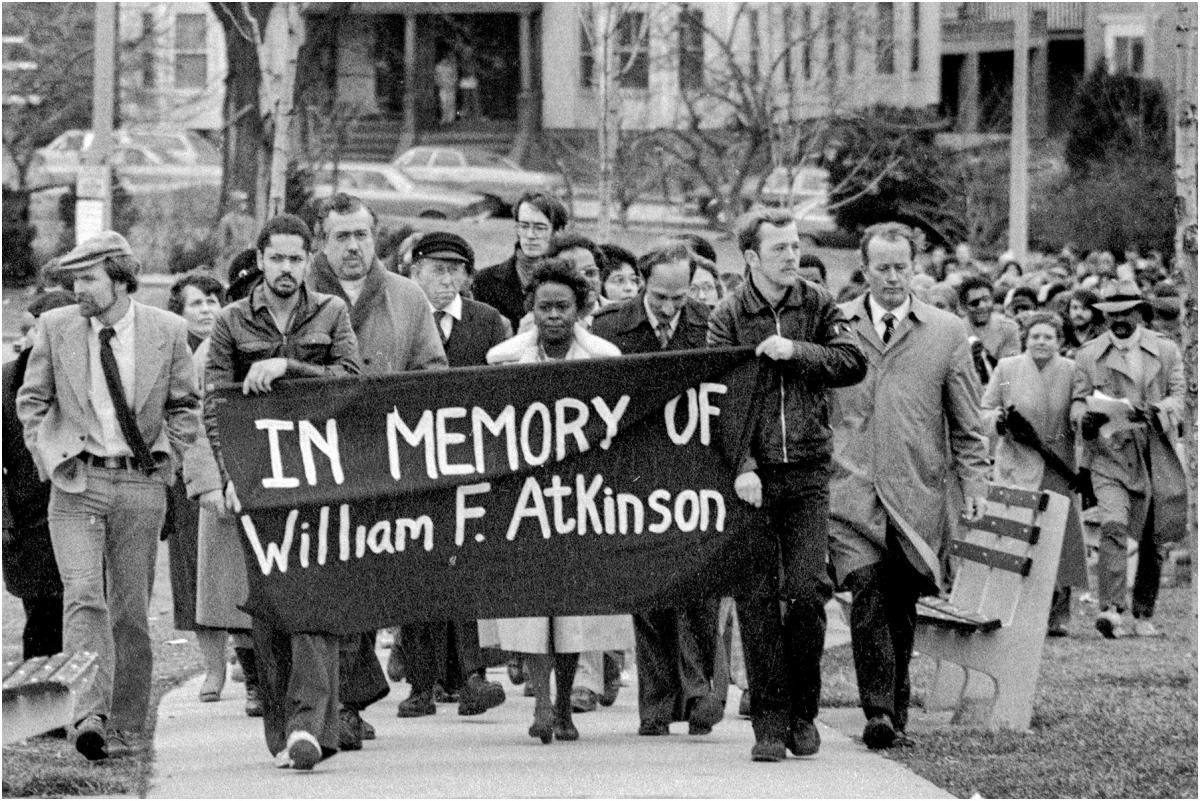

A recent graduate of Boston University, he was a legislative liaison for the Black Legislative Caucus, and one of his duties was to attend weekly meetings with community activists in Roxbury. He said the attack on Wilkerson stirred anger in the Black community even outside of Dorchester. A little more than a week after the attack, Lawton was among 700 people marching in Atkinson’s memory.

“When you had a gathering like that, a multiracial gathering, nobody had ever talked about anything like that happening before, so it was unprecedented,” said Lawton. “And I think it was even shocking to those racist gangs, almost like a feeling that they had gone too far… so it brought attention.”

Lawton also looks back on the attack and the march as coinciding with efforts to make Dorchester’s organizations and institutions more inclusive. The results could be seen in programming at the Boys & Girls Clubs of Dorchester, the establishment of youth councils, and, in 1983, the formation of the inter-racial All Dorchester Sports League, which Lawton would later serve as chairman.

“It was a bad start, but it was a kind of good start at that point,” he recalled. “We were at our lowest point as a community, and it was only up from there.”

The march was followed by an interfaith service at First Parish Church, with an almost total absence of elected officials. But there was speaking by clergy and local activists, and duty to the family dead, expressed by Atkinson’s twin sister, Francine Atkinson.

“Don’t let this act of violence or any other act of violence be kept secret,” she said. “Because, just as it happened to him, it could happen to you.”

Even as the march had set out from Uphams Corner, the message about what happened and the name of the person whose life mattered were plainly visible. “In memory of William F. Atkinson” was displayed on a banner wide enough to be held up by four people across.

The march in memory of William F. Atkinson on March 21, 1982, as it was approaching Rev. Allen Park and First Parish Church.

The marchers walked so quietly that it was possible to hear the engine of a police car escort. Near a church on Stoughton Street, worshipers in Sunday dress paused to look. A few other spectators stood up on a wall outside the Edward Everett Elementary School to see a winding column of people make its way along Pleasant Street. And, from a single three-story apartment building, faces looked out from eight windows.

The community was watching.

Chris Lovett is regular contributor to the Reporter and a veteran journalist who covered some of these events as a journalist with the Dorchester Argus-Citizen in the 1970s,

Community Watch Party for “The Busing Battleground”

Mon., Sept. 11 at 7 p.m. at the Community Academy of Science and Health

11 Charles Street in Fields Corner in Dorchester,

--Across from Fields Corner MBTA Red Line Station

--Parking in school parking lot, turn right before the school on the right

The award-winning filmmaker of this documentary, Sharon Grimberg, will speak before the showing of the documentary film that night.

A documentary of the desegregation and busing years in the 1960s and 1970s done by GBH’s American Experience. It covers the organizing ‘before busing’’ efforts of the Black community to improve education. And then the busing that followed Judge W. Arthur Garrity’s 1974 decision to desegregate the Boston schools. This was a momentous event in our city’s history. Many still carry the trauma of those days with them. The documentary will air nationally that night, but it will air first in Dorchester earlier in the evening!!

Sponsored by the Boston Desegregation and Busing Initiative which is organizing forums and exhibits on these events in 2023-2024. For more information, email LewFinfer@gmail.com