September 13, 2023

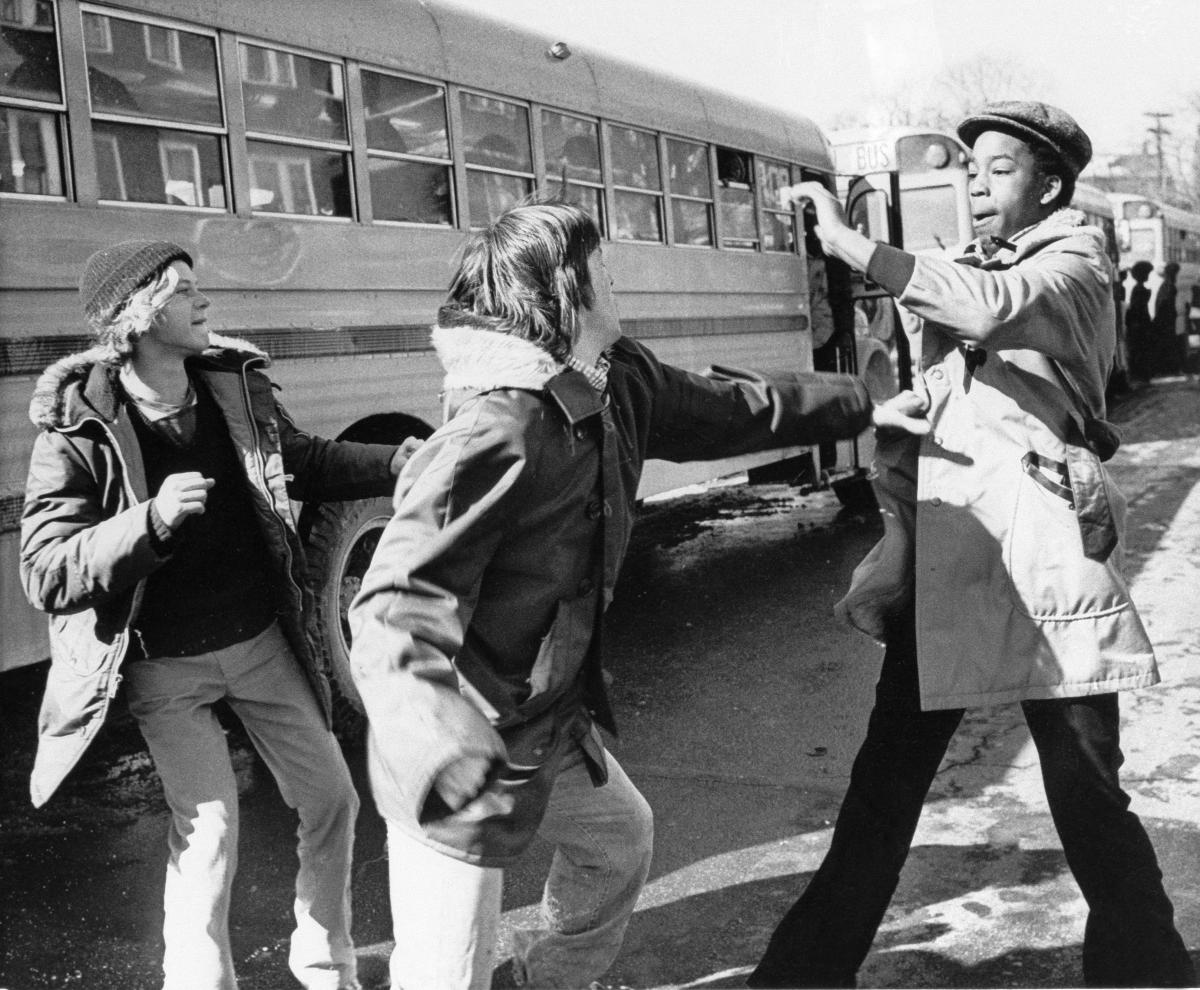

Students riding the bus to South Boston High School on September 11, 1975.

Associated Press, Boston Globe /Getty photo

The history starts with a dream and becomes a nightmare, only to reawaken as a halting voice of trauma or equanimity steeped in regret. Such was the “moral arc” of Boston’s “long road to school desegregation” in the PBS “American Experience” documentary, “The Busing Battleground,” which premiered Monday night before 150 people at the Community Academy of Science and Health in Dorchester.

Taking place almost 49 years to the day after the start of what many refer to as “court-ordered busing” in 1974, the screening was the first in a series of commemorative events organized by the Boston Desegregation and Busing Initiative, which includes several members who experienced the history.

Even before the screening began, one of the group’s co-chairs, Lew Finfer, a longtime community organizer, reminded the audience that the event was taking place in what was during the turmoil of the 1970s one of the few places in Dorchester where people of different races could feel safe attending the same community meeting. He then drew attention to the documentary’s last words, spoken by a pioneering Black journalist in Boston, Bryant Rollins, who passed in May 2022.

“If there had been a way for deep dialogue between Blacks and Whites, a lot of the conflict that arose in the sixties and the seventies was avoidable,” said Rollins. “People were in a state of violent agreement. What we agreed about was inefficacy of busing. White parents didn’t want it for their kids. They had different motivations and different reasons. And Black parents would have preferred not to have to have busing if they had quality schools. We did not slow down, take a deep breath, take a step back, and ask ourselves what’s possible together. That’s a tragedy. Everybody has lost.”

Despite the documentary’s title, much of its first hour shows the desegregation effort was not just about busing or the ruling of a federal judge who lived in Wellesley, W. Arthur Garrity. If there’s a central figure in the documentary’s first half, it’s Ruth Batson, a Roxbury mother of three who would become the chair of the education committee for the Boston NAACP and the Black community’s pre-eminent champion of educational justice.

White protestors shout at Black students as they arrive at South Boston High School on the first day of busing. Associated Press, Boston Globe /Getty photo

As historians have noted, champions of educational rights in Boston’s Black community go back as far as the 18th century. Likewise, as Ronald C. Formisano relates in “Boston Against Busing,” the white resistance to aims of the 1974 court order goes back at least a full decade. And historians have also placed the conflict over schools in a wider and longer struggle over access to housing and jobs.

The demands that Batson and other Black parents presented to the Boston School Committee in 1963 did not list busing. They did call for changes in enrollment policies that, in some cases, resulted in White students being bused to more distant White schools, which only made predominantly Black schools that were closer more racially imbalanced.

As Black plaintiffs later argued in their federal lawsuit, and as Judge Garrity ruled, the Boston School Committee was practicing de jure segregation, operating a “dual system” of education, with different levels of quality for students of different races. Added to the mix, as a sign of the members’ intentions, were their own comments as preserved by the committee’s stenographer.

Boston’s elected School Committee – all White in the decades up to 1974 – staunchly denied it was practicing segregation, blaming differences in assignment and achievement on residential housing patterns or what its members described as deficiencies of Black families—especially “immigrants” more recently arrived in Boston as part of the post-war “Great Migration.” But Garrity’s decision withstood appeals, and later debates have been less about the determination of a problem than the ensuing attempts to remedy it.

After the concerns of the Black community had been affirmed by a state commission and passage of the Racial Imbalance Act in 1965, the School Committee continued to oppose even modest remedies for segregation. As detailed in Formisano’s history, committee members such as Louise Day Hicks and John Kerrigan, along with combative political figures like Albert L. “Dapper” O’Neil, equated the demands of Black parents with the specter of demographic change. With long odds against winning elective office, the Black community in Boston was forced to pursue its agenda mainly through activism and litigation—at a time when unrest in many American cities made White populations more and more fearful of change.

By August of 1974, just a few weeks before the opening of school, Hicks, then a member of the City Council, warned Judge Garrity about the potential dangers that would be faced by students. She put more emphasis on predominantly Black areas, flagged by her as “spawning grounds for crime,” but she also dared the judge to assure all Boston parents that “no harm to their children will take place.” Years after the fact, it takes little imagination to read the letter as a veiled threat about the violence that would erupt in South Boston.

White and Black students begin to fight outside Hyde Park High School in Boston, Mass., Feb. 14, 1975. Associated Press photo

As is made clear in the second half of “The Busing Battleground,” there was plenty of harm to students of different races in different areas, but the intensity and organized character of violence was more pronounced in South Boston. Speakers in the documentary, like Formisano, depict the White resistance as an organized mix of terror and disruption, even if experienced by some as an aggrieved community’s way of belonging: the chants that pumped up acts of violence were the same that could have been heard at a high school football game.

If there had been more peaceful cooperation with busing, it’s possible that many White families would still have left the city or the school system. Fears of street violence outside one’s own neighborhood had long been a way of life in Boston, even among different White communities. But, starting in 1974, with the spike in chaos and the escalating cycle of retaliatory violence in parts of the city, the urge to bail out would have been even stronger.

Faced with breaking news coverage in 1974, people in Boston might have viewed White resistance as a spontaneous fury enacted mainly by teenagers and raucous adults. Under that surface, Formisano found what he called a “scorched earth” policy directed by leaders and marshalled through phone trees. As a longtime Boston educator, Al Holland, recalled about South Boston’s resistance in the documentary, “The community outside was controlling the kids.”

If the nature of organization was unique to South Boston, there was violence in other neighborhoods, Black and White. One White parent in the documentary, Joe Burnieika, described his decision to send one of his children to a school in Roxbury. He said the bus that picked up his son was stoned in his Savin Hill neighborhood for having Black students, only to be stoned in Roxbury for having White students.

For all the focus on violence, the documentary airs questions about the wisdom of assigning Black students to what had been predominantly White high schools in South Boston and Charlestown. Michael Patrick MacDonald, who lived through the South Boston turbulence described in his memoir, “All Souls,” argues that the neighborhood’s high school was not the right place to seek educational equity. If, as Formisano explained, the school was compatible with aspirations for the surrounding neighborhood, it was hardly the educational model pursued by Ruth Batson.

“The Busing Battleground” also applies the lens of class. Many of the supporters of desegregation outside of Boston were from the suburbs, which the US Supreme Court would exempt from measures such as busing. And, if the Boston School Committee sought political gain by tightening the boundaries of an educational ghetto, the regional pattern of discrimination in housing depended on racial covenants, redlining, and federal support for mortgages and highways.

For some viewers old enough to remember, this week’s screening was like a reunion and a throwback to the days of the Grover Cleveland Middle School, where racially mixed community meetings were at least a voluntary step toward change in Dorchester. But the harnessing of political discourse to threats of violence that became real could have made some viewers think of more recent events.

When the documentary shows US Senator Ted Kennedy in 1974 being swarmed and attacked by antibusing protesters on City Hall Plaza, he flees to an adjacent federal building, where the torrent of rage swells to a shattering of glass. In 2023, it’s hard to watch the scene without thinking of what happened at the nation’s Capitol with a politically mobilized crowd and multiple senators in flight on January 6, 2021.

For some older viewers, the sight of a Black attorney, Theodore C. Landsmark, being speared with an American flag by an anti-busing protester on City Hall Plaza in 1976 would have just been a repetition of the indelibly familiar photo by Stanley Forman. But the documentary showed other images from the scene, with Landsmark almost prostrate and protesters lining up to land kicks. What many had instantly perceived and remembered as a sadistic violation of a national symbol looked, if less worthy of a Pulitzer Prize, all the more crude.

On Monday night, Landsmark was among the viewers in the auditorium. On his way out, he stopped to talk with several people he knew from organizations he worked with in Boston over the past fifty years.

“It’s great to see the mix of people who experienced these events directly with the generation of emergent social justice activists,” he said. “The film should inspire a lot of dialogue across the country about where we have and have not progressed racially.”

As Mayor Michelle Wu and Boston School Superintendent Mary Skipper announced before the screening, the lessons from desegregation and busing would be used to generate dialogue with students in the Boston Public Schools.

“We need to do better for them,” said Skipper. “We need to learn from the past.”

But there were also times when dialogue in the film was halted by the long reach of trauma. That was the case when a South Boston resident who was opposed to busing, Bob Monahan, was shown talking about a White mother from the neighborhood who was terrorized by anti-busing militants after she joined a biracial school council. His flow of words broke down in mid-sentence, the silence punctuated by a fitful movement of hands and a discernible hush in the auditorium, like a deep breath.

One of the Initiative’s co-chairs, Karilyn Crockett, described the film as “very emotional.” Her grandmother, Mary Crockett, had been one of the plaintiffs in the desegregation lawsuit and active in earlier efforts to sway elected officials. Their goal, she said, was to “stare down the School Committee and stare down City Hall and wish for something else, wish for something more, which remains unfulfilled.”

One of the of the last comments at the premiere was from a viewer too young to have experienced the worst years of busing directly, Akiba Abaka, director of Good Trouble for the Boston Children’s Chorus, who expressed gratitude for the meeting space and the cross-section of viewers.

“We haven’t had time at all to be in this space about this topic,” she said. “And we are, to be honest—I’m going to say what is—there were moments that were extremely traumatizing to watch, and not because we’ve never seen it before—it’s because we’ve seen it before.”