March 29, 2023

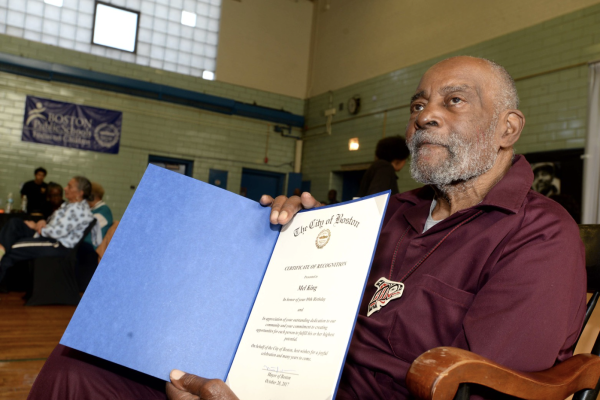

Mel King celebrated a birthday at the McKinley South End Academy in 2017. (File Photo via Don Harney/Mayor's Office)

Mel King, perhaps the most prominent activist and Black politician of Boston's 20th century, has died at age 94.

His son, Michael King, said his father died in his sleep Tuesday afternoon at home.

In a city that touts its history as a temporary home to two giants of the civil-rights movement, King was 100% home-grown.

His name is revered by generations of activists and artists, like Jamarhl Crawford of Roxbury. Crawford said King was "our Nelson Mandela... ambassador-like, statesmanlike."

The writer Junot Díaz — a colleague of King's at MIT — called King a person of "visionary emancipatory importance."

"Boston always be going on about the Kennedys, but they should really be building monuments to Mel King," he said.

King was a tireless organizer for decades — a natural leader, friends said — fighting against apartheid and multiple wars, and in favor of affordable housing, good paying jobs and more. Already in 1978, Ruth Batson, who started the METCO program, told WGBH she wasn’t aware of a promising city initiative that King hadn’t started or helped along — and always in a collaborative spirit.

"He doesn't want to stomp all over people," Batson said. "He believes in teaching as you go along, so that we all come along together — maybe in disagreement sometimes, but with understandings all the time."

King learned to co-exist from the start. He was born in 1928 to Caribbean immigrants, one of 11 children. It was a humble but happy upbringing, and shaped the sensibility of Mel King the man.

As a child, King recalled that he was once followed home by a man who was hungry and cold. Right away, his father — a dock worker and union secretary — welcomed the man indoors.

“He came in and was fed, and warmed, and given some food on his way," King told WGBH in 1983. "I’ll never forget that my father said, ‘No matter what you have, you always have enough to share.’ ”

King shared his whole life with Boston; he only ever left the South End at length for his four years at Claflin College, a historically Black institution in South Carolina. But at times, Boston took from him.

When King was in his mid-twenties, then-Mayor John Hynes labeled King's cherished South End neighborhood as a slum. The Kings and hundreds of other families were evicted. Twenty-four acres — blocks King remembered in his 1981 book, Chain of Change, as a cosmopolitan blend of shops and churches, Jewish and Armenian and Black and white families — were bulldozed.

That loss angered King, but it also propelled him into activism. In 1968, he led the construction of a famous "tent city" to block more such "urban renewal."

In the late 1960s, King threw himself into a new and militant mode of struggle. He was prepared to defend the new stance, saying that Black America had learned hard lessons from American history — from the mass killing of Native Americans to the internment of the Japanese.

"The alternatives of extermination and concentration camps are our frame of reference," he said.

Ever the optimist, King added that there was a better option on the table: the unconditional acceptance of African-Americans into a diverse and equal society — a revival of the lost world he'd loved as a child.

"I’m not talking about that ‘melting pot’ kind of thing," King said in 1968. "I’m talking about integration at the seats of power and decision-making. Without that, the rest of what we talk about is a sham."

King got his own seat at the table in 1973, when he was elected to represent Suffolk County's ninth district in the Massachusetts House of Representatives. Shortly after arriving on Beacon Hill, he fought for his right to wear a dashiki on the floor of the House. Six-foot-five, bald, bearded and radical, King raised some eyebrows.

But he tended to win people over. Gov. Michael Dukakis remembered "this guy, who was strong and outspoken, and had all kinds of courage. But he was also a very effective legislator!"

In his first term as governor, Dukakis worked — and sometimes warred — with King, whose agenda was broad and often surprising. He worked to expand community farming, protect community television, and to source clean and healthy food from across the state.

But that cooperative, progressive vision didn't always mesh with a parochial city, as when King failed to negotiate a last-minute deal to stave off the violent, mid-1970s blowback around court-ordered school desegregation.

Across the table was Ray Flynn, then the representative for an inflamed, largely Irish South Boston. The two were known to each other: they'd been rivals and teammates on the city's basketball courts.

In 1983, Flynn and King squared off again, as the two unlikely finalists in the race to replace Kevin White as mayor. The press sold them as a matched pair of public school grads from working-class origins.

King bristled at the comparison. Flynn had fought against busing and abortion rights. King was an anti-racist and feminist well ahead of his time, who attracted a "rainbow coalition" to his campaign.

Still, on election day, Flynn won with nearly two-thirds of the vote.

True to form, King didn't mourn; he organized. The next year he demanded that President Ronald Reagan follow Massachusetts' lead and pull American dollars out of South Africa.

In late life, King's voice diminished to a whisper. But still he spoke: as a professor at MIT, as a mentor and host in Sunday round-tables at his home, paired with his beloved wife Joyce. And he served as a coach to a new generation of activists and politicians.

Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley, a Chicago native, said King was a life-changing mentor and model in her adoptive home.

"He [was] supportive and encouraging, but doesn't just endorse an idea because you have one," Pressley said. "I have certainly been a better lawmaker for his counsel ... but more importantly, I hope that I'm on task to be a better person."

Today, many of Boston's Black and Latino residents still find themselves on the wrong side of socio-economic chasms: in segregated neighborhoods, with worse health outcomes and far less wealth.

But that doesn't mean King failed to build a better future. He tended to think of his life's work as a football game, said Jamarhl Crawford

"It's about, 'We got two yards on this play... four yards on this play' — moving incrementally closer to the goal," Crawford said.

King moved the ball forward on multiple fronts. Twenty years after his first high-profile protest, the city opened 269 units of mixed-income housing just blocks from Copley Square, and named them the "Tent City" apartments. King pushed for the introduction of computers and technology in city classrooms. And he kindled interest into causes of the utmost urgency and relevance, from reparations for slavery to environmental justice.

Boston, at its best and at its worst, made Mel King. But then, slowly but surely, Mel King remade Boston — and the world around it.

This article was first published by WBUR 90.9FM on March 28. The Reporter and WBUR share content through a media partnership.