March 9, 2022

During the late 1930s, a 30-something man who was living in Dorchester’s Savin Hill neighborhood and worshipping at St. Margaret’s Church, joined up with a German Schutzstaffel (SS) officer masquerading as an official in his country’s consulate on Beacon Street in Boston in a sub rosa effort with others aimed at keeping the United States from getting involved in the preparations for war taking place across Europe in the face of Adolf Hitler’s militaristic and diplomatic provocations.

That is the report from Charles R. Gallagher, a Jesuit historian at Boston College whose recently released book, “Nazis of Copley Square – The Forgotten Story of the Christian Front,” covers a great deal of ground in giving an account of the short-lived but vital in its time and place Catholic-directed organization, which was formed in 1939 as a counterpoint entity to the Communist International’s Popular Front.

Francis P. Moran was born in South Boston in 1909, the oldest of the 11 children of immigrant parents from Ireland’s County Mayo. He grew up as a committed Roman Catholic who had spent three of his teenage years in a Franciscan seminary, an experience that included discussions about the agency of the Jews in the crucifixion as Catholic doctrine that, the author suggests, enhanced his value to a foreign government whose deepest ideology centered on ridding Europe of the Jewish race.

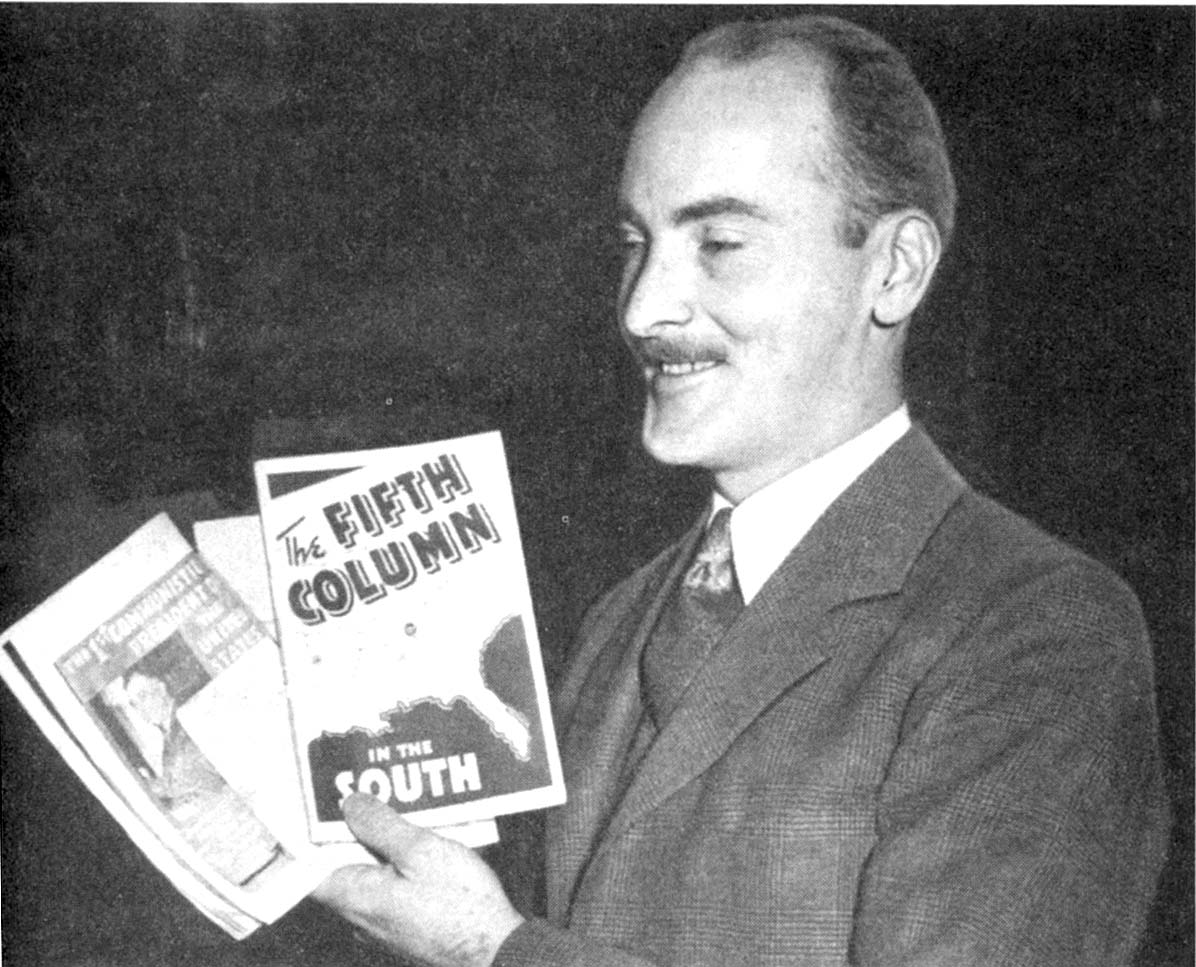

This photograph in the book, used courtesy of the Boston Herald-Traveler photo morgue in the Boston Public Library, shows Francis Moran displaying some of the Christian Front’s pamphlets. In January 1942, police seized these and other materials from Hibernian Hall in Roxbury.

Gallagher points out that the new organization, a phalanx of mostly Catholic individuals, saw itself “as the advance guard of a holy war against Communists and Jews – groups they saw as one and the same under the umbrella term Judeo-Bolshevism.” He adds, “At its heart, the story of the Christian Front is one of priests who drew upon some of the most vibrant theological movements of the Catholic Church [the Mystical Body of Christ; Catholic Action] and used them to justify evil” as they readily rationalized the malign actions of the group’s front men.

A discussion about how Catholic doctrine buttressed justifications for the Christian Front’s more egregious representations takes up substantial space in the narrative as does a look back at the now mostly forgotten Holy Name Society, a men-only organization formed in the late 1800s and aimed “at addressing problems of modernity by curbing blasphemous speech and bringing men back to the regular attendance to the sacraments of the faith.”

One point of this extended lesson in theology and Catholic mores seems to be that those who enlisted in the Christian Front, taking encouragement and support from their priests, used a deep devotion to their Catholicism and its doctrinal teachings as a defense of their statements and activities promoting depravities like anti-Semitism. In short, they were protecting their faith against “Judeo-Bolshevism” while the Nazis, with their assault on the Soviet Union in mid-1941 and their death wish for the Jewish race, were fighting the same fight.

Moran, who had taken on and left, or had been fired from, a number of jobs during the late ’20s and early ’30s, is presented in length as an exemplar of that point. By mid-1939, he was publicly known, mostly from his own writings and speechmaking, as the director of the isolationist Committee for the Defense of American Constitutional Rights with an office in the Copley Square Hotel.

Around that time, the author relates, he “fell into the arms” of the Nazi operative Herbert Scholz, who arrived in Boston in late 1938 to begin his exercises in espionage. Over the next few years, Moran, “who had no state secrets to reveal, dedicated countless hours to causes Scholz directed,” among them “the defeat of FDR in 1940; and stirring up anti-Semitism in the city.”

Egregious examples of the latter activity from the mouth and pen of Moran abound in this book, none of them worth recounting in this review. But the participation of officers in the Catholic-dominated Boston Police force in the anti-Jewish violence in the Boston of those and later years does come in for some scrutiny here.

After his few years of notoriety, the Allies’ war against the Nazis and the other Axis powers took precedence over everything else and Moran and his fire and brimstone personality faded out of public view. He enlisted in the Army in late 1943, got married, had a family, and died at age 62 in 1971 in West Roxbury, his last job a reference clerk’s position with the Boston Public Library.

Notable players move this story along: Rev. Charles E. Coughlin, the originator of the Christian Front, was the pastor of a church in Detroit who organized a national broadcast apparatus that by the mid-1930s allowed him to deliver venomous anti-Jewish rhetoric directly to millions of listeners across the country on Sunday afternoons. And there was J. Edgar Hoover, who along with his cadre of FBI agents – and, from time to time, members of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s intelligence team – seemed bewildered as to how to deal with Christian Front activists like John F. Cassidy, a New Yorker whose militaristic approach to the realization of the Christian’s Front goals landed him and his adherents in court in 1940 under an indictment for seditious conspiracy to upend the United States government and an assortment of weapons charges involving, among other items, the making of pipe bombs. The defendants ultimately were acquitted of all major charges, their “coup” seen as clownish.

Rev. Gallagher has resurrected a historical curiosity that has rarely found purchase in histories of the years when World War II turned from threat to catastrophe. In the large books of memory, the Christian Front is a footnote, but his scholarship reminds us that it was not so long ago that a band of Catholics – leaders and followers – openly disparaged Jews for being Jewish on the streets of Boston, and found doctrinal reason to justify what they said and did.

“Nazis of Copley Square: The Forgotten Story of the Christian Front.” Copyright© by The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Harvard University Press