January 26, 2022

Rebecca Zama on her multi-lingual songwriting: “What counts is the emotion that’s put behind it.”

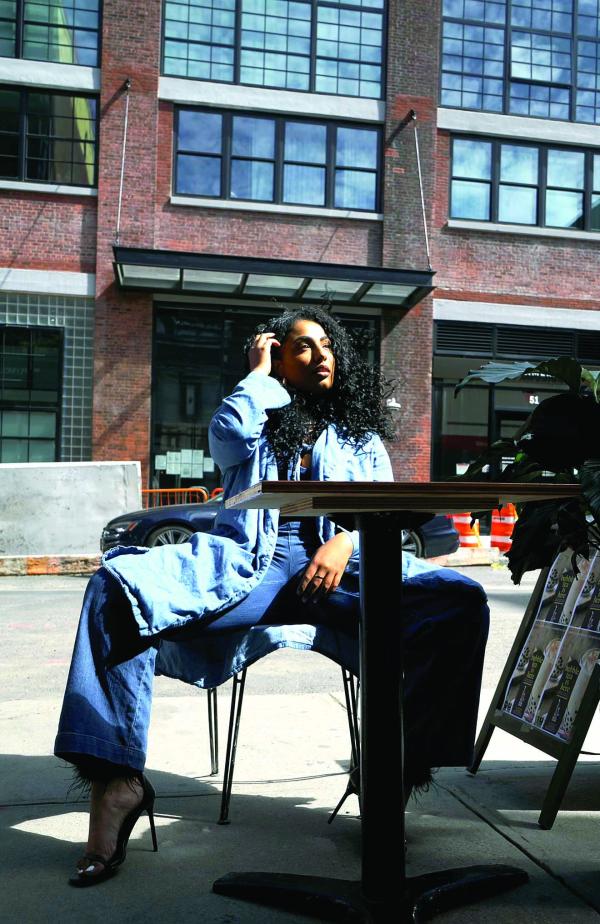

Photos courtesy Rebecca Zama

Hunched in a dimly lit Dorchester recording studio last November, the Boston-raised singer Rebecca Zama tests her track: riffing in English, belting in Haitian Kreyol, murmuring in Spanish, and, when forgetting a lyric, cursing in French. As the young artist seamlessly flits from language to language, her hands dancing in the air, her pink Converse sneakers tap to the beat and a fusion of notes and sounds fills The Record Co. studio in Newmarket Square.

Afro-Cuban percussion beats thrum from her pulsating computer, providing a background for Zama to sing. She only stops to take another sip of her ever-present iced coffee that is half-finished at 6 p.m.

A first-generation Haitian American born in Washington, D.C., Zama is enchanted by the rich sounds of so many different cultures. As she sings, her head bobs to the rhythm, her long black hair swaying behind her.

“If I can’t say something the way I want to say it in English, I can say it in French,” she said. “It just helps me to think outside the box and not confine myself during my songwriting.”

In the coming days, the 22-year-old Zama plans to release the recording she was working on in November, “Oh My My,” a song with lyrics in four languages. The “outside the box” thinking she talked about three months ago has long been a staple of her artistic approach, one that attracts critics who want to see her stay inside that box, to compartmentalize, to label.

Over the years, Zama has faced pressure from Haitians telling her that she doesn’t seem Haitian enough, R&B fanatics telling her that she should just “pick a sound” and onlookers wondering how a singer can self-identify as “genreless.”

Zama is no stranger to dropping new music. In 2020, she released a series of singles — poppy, jazzy ballads that surpassed previous songs in thousands of listeners. Although she hasn’t released a full-length album since her teenage years, she’s hoping that the preparation for her latest work will pay off.

Niu Raza, a fellow artist and friend, said that Zama was very “unsure of herself as a musician” when they first met five years ago. “People expect you to choose one side or the other,” said Raza. “Maybe the Haitian community wanted her to sound more Haitian than the Black community, and the Black community wanted her to sound more Black. And she was both, but she just didn’t want to pick sides.”

Rebecca’s mother, Nunotte Zama, says it took a village to raise her daughter, who was brought up in Melrose, but is really a child of Greater Boston’s tight-knit Haitian community. The young singer and activist has long been a fixture at churches and community events in Mattapan, Hyde Park, and Dorchester. Her mother encouraged her to embrace her roots and learn traditional Haitian songs, but also express gratitude for her home in America.

One of the first songs Zama learned was the Haitian national anthem. In 2018, she got a high-profile opportunity to perform the “Star Spangled Banner” at a Red Sox-Yankees game at Fenway Park.

From a young age, Zama has surrounded herself with friends from diverse backgrounds. She felt immersed in a variety of cultures, and wanted to find a way to translate that into art. It wasn’t long before she began expanding her performances and seeking wider audiences.

Instead of performing at family-fun Haitian events, she began sneaking into bars and past bouncers to perform at local clubs. Soon, she was facing larger and larger crowds. Her music became more than just a hobby—it’s equally a reflection of her dreams and a vehicle for her activism.

Zama was deeply affected by the 2010 earthquake that devastated Haiti’s capital city. She lost some extended family members who perished in the rubble in Port-Au-Prince. The shock was immediate, especially since she had just 11 days before arrived back in Boston from a visit to Haiti.

As Zama grew older, she became more aware of the discrepancies between herself and her family in Haiti. “A lot of these kids that I played with, the only difference between me and them is just opportunity,” she said. “If there was a fork in the road, maybe my mom went to the right and others went to the left.”

In 2012, Zama helped her mother launch the Haiti Global Youth Partnership, which supports L’Asile, the 33,000-person town where Nunotte grew up in a one-bedroom home crammed with 12 people.

“My kids could have been born in L’Asile and we would have all been subjected to the same fate… of not having running water or the ability to get a primary education,” said Nunotte, who’s now a lawyer. “They realize how blessed they are, and I don’t want them to forget where we come from.”

The nonprofit organization, which focuses on alleviating issues that include unsafe water and food insecurity, supports hundreds of L’Asile’s children.

As Zama’s following as a recording artist has grown, the advocacy work that she does keeps her rooted. She’s “just Rebecca” in that role. “As an artist, you are the vessel of your career,” she says, “it quite literally depends on you, right? So, I think it’s easy to kind of forget about the world around you.”

Zama knows that music, in all its complex forms, is universal. It bridges divides between Haitians and Americans; the young and the old; the native speakers and the foreign-born; and artists and advocates alike.

“Just because I’m saying something in one language and somebody is saying something else in another one, what counts is the emotion that’s put behind it,” she says. “When you’re able to express yourself in a way that’s organic and natural to you, it creates raw and honest music that will overcome whatever language barriers may exist.”