December 14, 2022

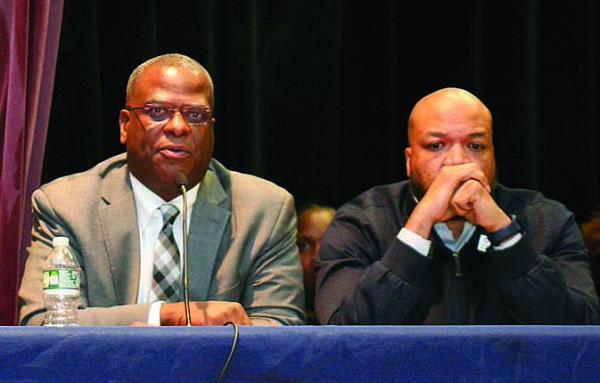

Police Commissioner Michael Cox and the city’s senior adviser for public safety Rufus Faulk, above, were all ears as residents like Marvina Patterson aired their frustrations at last Thursday’s meeting. “I don’t go to restaurants in my neighborhood because I’m fearful of what might happen when I’m there,” she told them.

Seth Daniel photos

Statistics kept by Boston Police show that shootings and gun violence are at an all-time-low across Boston. But, in pockets of Dorchester and Mattapan, residents say that fear and anxiety about shootings is at an all-time high. Grappling with how those two realities can both be true at the same time was a central theme at a City Council-sponsored hearing last Thursday evening at the Lilla Frederick Middle School on Columbia Road.

The hearing was organized by City Councillors Brian Worrell and Tania Fernandes Anderson in the midst of a long stretch of shootings, homicides, and aggravated assaults. However, it was a broad-daylight shooting on Dec. 5 in front of the Joseph Lee K-8 School on Talbot Avenue just after school hours that grabbed the spotlight in the moment.

Councillor Brian Worrell.

“The question we have to ask is who is Boston safe for,” said Worrell. “Outside the Joseph Lee School in District 4 on Monday more than 25 shots were fired…Kids took cover in buses and under desks and the school was on lockdown. Two people were injured by gunfire.”

He added: “Crime stats may be on the downward trend, but this kind of violence looms large for District 4. I am tired of offering thoughts and prayers. There should be zero shots fired. One shot fired each year is too many.”

Mayor Michelle Wu, who did not attend the hearing, talked about the issue with the Reporter afterwards. “People’s memories and life experiences stretch back to include all of those incidents for many lifelong Bostonians, particularly when the fear of violence affects your life more than what any numbers would tell anyone,” she said.

“That is what we really need to connect with our communities on,” she said. Part of our responsibility is not just to understand and track data, but to get out in the community and ensure we are in constant dialogue and planning and working alongside community members block by block.”

While her administration has been criticized in Dorchester and Mattapan for seeming distant or uninterested in the impacts of violence, Wu said, “I take every single safety incident in our city extremely personally,” she said. “It’s our kids that we’re all responsible for. It’s our family members, our community, and my priority is ensuring that we’re not just running to respond to each incident after it’s happened, but changing the system…”

About 100 people, including police officers, residents, and non-profit leaders turned out for the hearing, which was driven mostly by testimony from people in the community. In his remarks, Police Commissioner Michael Cox affirmed that he cares deeply about the situation, and that the BPD is working to stop the violence. His presentation included words from crime analyst Shea Kelly, who noted that crime numbers citywide were headed for a historic low in 2022.

Former Roxbury resident and street outreach worker Jed Hresko returned for the hearing to offer his thoughts.

Rev. Dr. Bernard Coulter said the community needs to re-learn how to value life.

She noted that there had been 173 fatal and non-fatal shooting victims in Boston this year, a number that is on track to be the lowest in 22 years. That said, she produced a map that tracked shootings and noted that the “hot spots” were becoming smaller and more concentrated – leading to small pockets that feel a constant barrage of violence.

“There are spots that are consistent,” she said. “The concentrations are in Roxbury, Dorchester, and Mattapan, but specifically Franklin Field, Grove Hall, and Four Corners. The exception is in Uphams Corner, where it’s the lowest we’ve seen in [a long time].”

One key concern is the number of juveniles being arrested with firearms, which is up 82 percent over last year. There have been 130 juvenile firearm arrests, and of those, 21 individuals were arrested twice. Meanwhile, repeat illegal gun offenders of all ages were a problem as well, with 39 percent of those arrested for firearm offenses having had prior arrests in Boston for the same thing. Of that percentage, 79 people had three or more firearm arrests in Boston.

Transit Police Detective Mark Gillespie talked about a program they run quietly to help identify young people in need of assistance.

Rufus Faulk, the mayor’s outgoing senior advisor for public safety, fought back emotion when recalling the scene last July on Ellington Street where 15-year-old Curtis Ashford was murdered.

“What I saw there I’ve never seen before, and I’ve been doing this a long, long time,” he said. “There were about fifty 13- to 17-year-olds standing there drinking Don Julio (tequila). It was almost performative in that they were doing what they thought they were supposed to do on a scene and like a badge of honor in that they could wear a pin commemorating their friend. For me, it was eye opening that our young people were that hurt.”

He added: “When I was growing up, I might know what happened in my neighborhood, but I didn’t know what was happening in other parts of the city. We’re overexposed with social media and re-traumatized every time, so it feels we’re in a constant state like Baghdad…As service providers, we’re traumatized as hell.”

Lisa Searcy, a community activist and liaison for Councillor Erin Murphy, shone a light on the fact that many youths are hurting, and they are also dying from drug overdoses and suicide.

Radio show host Melinda Aguilera said the proper resources won’t arrive in the community until white people are also regular victims of violence.

Police behavior was not off the table at the meeting. Residents were not calling for the abolition of the police as much as they were calling for the police to respond quicker and to understand the community better.

“I don’t go to restaurants in my neighborhood because I’m fearful of what might happen when I’m there,” said Marvina Patterson. “But I went to a restaurant on Washington Street in May because it was recommended, and I found gentleman outside a barber shop and the restaurant smoking weed and drinking. I remember telling [a police officer on the scene] that if this were in Brookline or Cambridge, it wouldn’t happen. He told me that we weren’t in Brookline or Cambridge. At that point, I nearly caught a case myself…We are looking to alleviate the violence when we call for these things and for loud parties and no one cares.”

Grace Richardson, whose son was murdered in Dorchester in 2017, said violence has been going on since the 1990s and assistance programs need to be better evaluated for success.

Asked Grace Richardson, whose son Chris Austin Jr. was murdered on Ashmont Street in 2017: “What will you give to our children who are scared to walk the streets and may be arming themselves to feel safe? This has been going on since the 1990s. They say we live in a place where our children are marked for death. We need to stop people from profiting off the lives of our people. It’s not about people getting funding…We need to have the data. You’re funding programs – let’s see the data. If it’s not effective, don’t fund it.”

Trepetta Simmons called on the police to forge ties with the community as strong as they do among themselves. “I don’t need you to protect me,” she said. “Just be a real person; come here and be a real human being and acknowledge you have tough times, and we have tough times. The bond you have between each other with the Blue Line; you need to expand beyond that Blue Line and come over on the Black side as well. Get to know who we are.”

A major piece of the discussion was also about adult criminal behavior, with several residents noting that dysfunctional adults are shepherding wayward youths.

Grove Hall’s Michael Kozu asked everyone not to ignore adult behavior by pinning all the bad news on the area’s youth.

“Many adults are doing this violence as well and we need to address that, too, and not just put the blame all on the young people for what is an adult problem,” said Mike Kozu of Grove Hall’s Project Right.

Added Shamika Woumnm, a city street outreach worker and resident of Grove Hall, “You need programs where the young people don’t age out…You might be 30 in age, but mentally you’re not there. If you go to prison at 17 and don’t come out until 27, you’re still 17 mentally. You just aged 10 years physically.”

T. Michael Thomas runs the ‘Trades Not Triggers’ program that he said has been ignored by the city.

Some attendees talked about programs like Trades Not Triggers, which is run by T. Michael Thomas, that are seemingly not recognized by the city, while others asked the city to do more to identify the “special education to prison” pipeline in the schools.

Many audience members and presenters noted that the entire community needs to have a private conversation about overall behavior and well-being, a point made by Faulk:

“We have to have a closed-door conversation as a community without the cameras about this culture and how we talk and how we talk to each other – how we backbite each other…That’s another conversation, but not a City Council conversation,” he said.