March 23, 2022

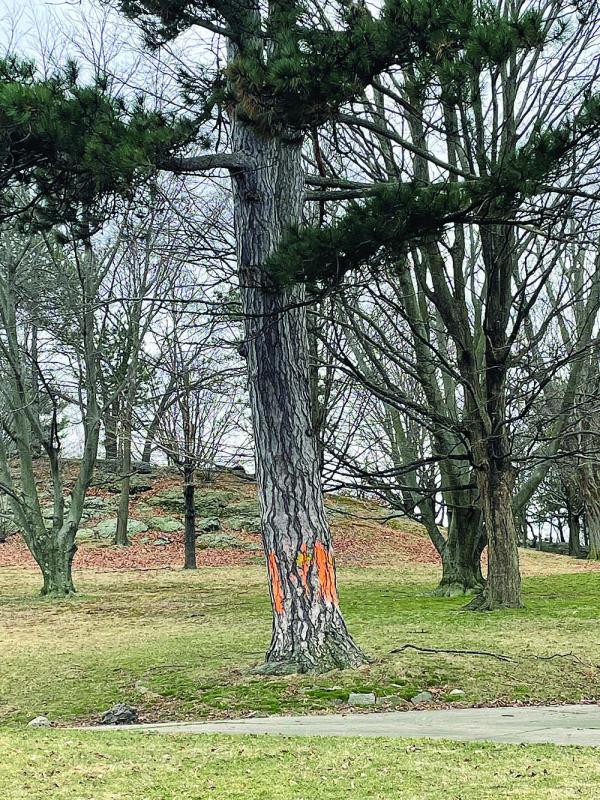

A mature tree inside Roxbury’s Malcolm X Park, one of many that have been marked for removal. Bill Walczak photo

Boston mayors have pledged to increase the city’s tree canopy for decades, and while the latest effort to do so seems to be in earnest, we have heard that refrain before. And yet, the extent of the canopy declined from 29 to 27 percent over the last 12 years.

Bottom line: Our city departments don’t make trees a priority.

Boston needs to add trees everywhere, but especially in densely populated neighborhoods. As our planet continues to heat up, trees protect dense urban communities from heat domes, which are high-pressure weather systems where hot air is trapped over a single geographic area. Heat domes can keep temperatures over 100 degrees for days or weeks, and they can be very dangerous for elders and those with medical conditions that weaken the body.

Boston’s chief of Environment, Energy and Open Spaces, Dorchester’s Mariama White Hammond, has said that Franklin Park provides protection from heat domes for the neighborhoods adjacent to the park. But further growth of the canopy has been getting more difficult as Boston gets fully developed and loses the little remaining privately owned undeveloped land in our geographically small city. This alarming fact makes the city’s lack of involvement in protecting two large parcels an abdication of leadership.

In 1885, Frederick Law Olmsted designed Franklin Park, which was intended to be Boston’s Central Park, with woodland preserves and areas for recreation. In 1949, the state took control of 13 acres to build the Shattuck Hospital. Now the state is relocating the hospital to the South End and demolishing the building. That land could be restored to the park, where it would add to the tree canopy. However, the state has decided that it would rather have buildings for social services replace the hospital.

I am a strong advocate for social services, but the proposed services could be placed on land nearby currently owned by the MBTA. The city isn’t intervening with the state’s plans, thereby losing an opportunity to restore 13 acres to Franklin Park. Many environmental groups – and former governors Mike Dukakis and Bill Weld – strongly support restoring the hospital land as park land. For more on that issue, visit emeraldnecklace.org.

The second parcel is 24 acres of woodland near Hyde Park and Roslindale called Crane’s Ledge. The owner of the property, Jubilee Church, has decided to sell the land to an apartment developer who plans to put 270 units and 415 parking spaces there. To date, the Wu administration has not stepped in to save the woodland. Allowing the apartment complex to be built will reduce Boston’s tree canopy more and eliminate the opportunity to make one of the last few private woodlands into permanent urban wild spaces. The city should procure the property. Advocates for preserving the site have their own website, savecraneledgewoods.org.

Real estate interests are the most powerful within Boston; they’re also a stubborn barrier to the canopy’s growth. City agencies like the Boston Planning and Development Agency (BPDA) have a history of favoring developers, so trees are typically the first casualties when construction starts. Until the city gets serious about protecting trees when giving permits for building projects, we will continue to see trees removed from land that can be built upon.

Developers should be required to provide a tree impact statement and plan. Chopping down mature trees and replacing them with saplings doesn’t cut the mustard.

While it’s not surprising that the BPDA favors development over nature, it is wrong to assume that you can’t have both. We all want to see more housing developed, but not everywhere. Our communities also need nature. We can add greatly to the housing stock by increased density near transportation hubs rather than increased sprawl that removes Boston’s remaining open spaces.

It’s not just the BPDA that is making decisions that reduce tree canopy. Just last year, the city dropped plans to remove 124 mature shade trees from Melnea Cass Boulevard after community protests. Then-City Councillor Michelle Wu noted: “I’m hopeful and determined that the new plans will reject false choices between safe transportation infrastructure and public health — our communities can and should have both.”

The Parks Department has also seen trees as problems. In 2021, its workers cut down about a dozen mature, healthy trees in the redevelopment of McConnell Park in Savin Hill. It was only through the intervention of neighbors that other trees were saved.

Last week, it was disclosed by the Boston Herald that the Parks Department planned to cut down 54 mature shade trees in Malcolm X Park in Roxbury. The department said that one of the reasons was to add wheelchair accessible paths, which brings to question whom the Parks Department hires for landscape architects for these projects. The area where the 54 trees are to be removed— unless the city halts the removal— is a wooded area that is part of a hillside with lots of open space. Paths that curve around 100-year old-shade trees would seem to be appropriate for this space, but apparently the designers could not figure out how to do that. Meanwhile, dead trees are ignored by the Parks Department in neighborhood parks.

Lastly, the process for expanding the street tree canopy has to be changed. A total of 875 people have signed a petition to add trees on Dorchester Avenue between Columbia Road and Freeport Street, a thoroughfare that has sections with no trees. Dorchester Avenue is the main boulevard of the largest and most diverse neighborhood of Boston, a neighborhood that, were it a city, would be one of the largest in Massachusetts. Yet, there can be no comprehensive tree planning for this area, as the city is insisting that the plan developed by the Dorchester Avenue Vision Committee must have individual agreements of the residents or owners of properties adjacent to the city-owned sidewalks where trees would be planted. This is Dorchester’s main street, not some side street. No wonder we are losing tree canopy.

If the Wu administration would like to protect Boston’s environment and increase the tree canopy, the above key areas need leadership and action.

Bill Walczak is founding president and former CEO of the Codman Square Health Center. He lives in Dorchester.