August 3, 2022

Where can I begin to tell about what Bill Russell meant to me and my generation of Boston basketball fans?

When Russell arrived in Boston just before Christmas day in 1956, he had won gold with the USA team in the Olympics and had led his college team at the University of San Francisco to two national NCAA championships. Still, he was mostly an unknown quantity for us Boston fans. There was no SportsCenter showing video highlights and the Boston press did not have much opportunity to see his college career play out 3,000 miles away on the Left Coast.

Our Celtics mostly had local roots. Holy Cross was a basketball powerhouse then, the source of familiar names like Bob Cousy, Togo Palazzi, and that year’s eventual rookie of the year, Tom Heinsohn.

Russell was one of the first Black athletes Boston would come to know well, but he wasn’t the first Black player on the Celtics team. That was Chuck Cooper, who was a Boston pick in the 1950 draft and played with the team for four seasons before moving on to Milwaukee.

Our Boston Braves had been home to speedy 1950 National League Rookie of the Year Sam Jethroe, who thrilled us with base-running for three seasons before he was sent to the minors as the team decamped to Milwaukee in 1953. And it would be several years before Pumpsie Green and Willie O’Rea would put on Red Sox and Bruins uniforms.

The Boston Celtics in the early years were a close-but-no-cigar outfit, lacking a dominating presence in the middle of the lineup. Walter Brown, the man who owned the old Boston Garden, was looking for something new to sell seats at the big sports arena on Causeway Street. Until the mid-1940s, Brown’s venue was singularly a hockey arena, with the occasional ice show (the Ice Follies and the Ice Capades), track meet (the annual BAA tourney), circus, professional boxing and wrestling matches, and even touring rodeos headlined by movie cowboy Gene Autry and radio/TV talker Arthur Godfrey.

But Brown and his fellow ice arena owners were looking for more regular events. After World War II, several pro basketball leagues were assembled, evolving over a decade into today’s NBA.

In those early years when Harry Truman, then Dwight Eisenhower were in the White House, pro basketball struggled to establish a fan base.

Assembling his team in 1946, Brown named them the “Celtics,” presumably to appeal to our city’s vibrant Irish population.

But in those early years, the team sold few tickets, and relied on doubleheaders with other pro teams and the occasional exhibition games featuring the Harlem Globetrotters to put Boston people in the seats. The early ‘50s team featured Cooper and Kevin Joseph Aloysius Connors, a/k/a Chuck Connors, who would later become an actor and star in a hit TV show, The Rifleman.

The 1956 team featured a former Holy Cross star named Bob Cousy, a coach named Red Auerbach, and a big fan favorite with a smooth outside shot named Ed Macauley. But St Louis native “Easy Ed” asked to be traded to his hometown team, which led to Auerbach sending him home in return for the rights to draft 6-foot-9 center Bill Russell, whose team at the Jesuit college in San Francisco was winning two national college championships.

For me, still a pre-teen fan who considered Easy Ed a hero, the trade was perplexing. Why would our Celtics give up on a star, our leading scorer, and add a tall Black man reputed to be a weak scorer, but maybe with an upside as a good rebounder.

We were told Russell was tall, and lean, a rebounder but not a scorer. The successful basketball centers in those days were bulky, elbow-throwing, physically strong high scorers like George Mikan and Clyde Lovellette of the Lakers (they were in Minneapolis then). Mikan had to retire at age 30, his career shortened by game injuries (fractured legs, broken bones in his feet, fingers and nose.) Our own Bob Brannum, a tough and mean Celtics forward, averaged 250 fouls a year, and usually fouled out before games’ end.

The Celtics in mid-decade were fun to watch, mainly because the Cooz was a basketball magician- his game was filled with amazing dribbling displays and behind-the-back passes. Teamed with the high scoring shooter Bill Sharman, the Cousy/Sharman tandem were called the greatest backcourt duo of all time. But those Celtics could never quite win a championship.

Then, like a Christmas present, Russell arrived in Boston in December 1956 and changed everything.

Boston sports fans have been fortunate to have some highlight heroes in the major sports: the Red Sox had Ted Williams, the Bruins had Bobby Orr, and the Patriots had Tom Brady, and the 21st century generation of baseball fans had the thrill of cheering for David “Big Papi” Ortiz.

But for me, the hero of heroes was Bill Russell. When he wore the green uniform, we expected that every new season would bring an NBA championship. And it usually did.

In those early years, my dad would take me to Sunday afternoon games, when walk-up tickets were always available. As a teenager, my good fortune was to work as a vendor at the old Boston Garden, so I was there for dozens of Celtics games, including six or seven match-ups between Russell and Wilt Chamberlain.

There was nothing like the thrill in the Garden when the C’s would take over a ballgame: Russ would block a shot, control the rebound, send an outlet pass to Cousy, KC, or Sam Jones, downcourt to Frank Ramsey or Tom Heinsohn for two quick points – then repeat, repeat, and repeat on a three-minute fast break run, of 14, 18, 20 unanswered points. It was a freight train, fast and unstoppable. The Garden crowd – often 13,909 of us – would go delirious in excitement!

With two or three minutes left in the game, the Celtics would call a timeout, and Bill Russell and our other stars would walk off the court to an ovation, while Auerbach lit up a victory cigar as he sat there, smugly on the bench. Talk about taunting!

There was nothing like it in sports, then or now, and it all began when Bill Russell came to our city and changed basketball forever.

How lucky was I to have seen him play basketball for my team. Bill Russell firmly and ferociously embodied social norms of justice and equality, values that I have shared over my lifetime. May he rest in peace.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Sidebar: Report on Russell’s Garden debut: 6 points, 16 rebounds, 1 assist

by Tom Mulvoy

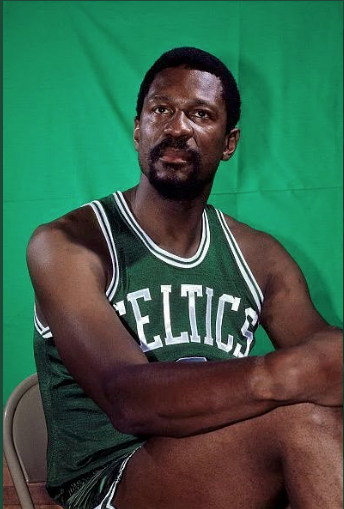

Bill Russell, the all-conquering college basketball star with consecutive NCAA titles at the University of San Francisco and an Olympic gold medal in hand, walked onto the parquet floor of the Boston Garden early in the afternoon of Sat., Dec. 22, 1956, to begin a 13-season professional career with the Boston Celtics that to date – 66 years later – allows for no one-to-one comparison in the history of organized sports.

I was there, age 13, with 11,051 other fans, including my older brother Mark, to watch the show, which ended with a Boston win over the St. Louis team via a buzzer-beating pop shot by Celtics Hall of Famer Bill Sharman, moving a Boston Globe sports department editor that night to emote an eight-column “CELTICS COP SIZZLER” “headline in a type size ordinarily reserved for the beginning or end of a world war.

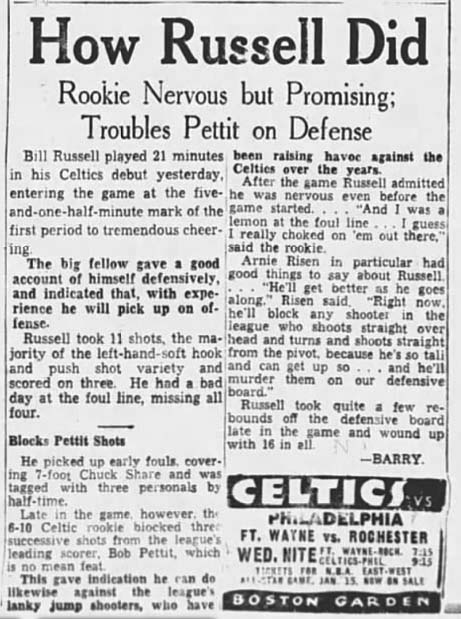

In a sidebar to his game story the next day, veteran staff writer Jack Barry saw promise for the team’s new center, who had made 3 of 11 shots for 6 points, taken down 16 rebounds, and accounted for a single assist:

“The big fellow gave a good account of himself defensively, and indicated that, with experience, he will pick up on offense. … Late in the game, the 6-10 Celtic rookie blocked three consecutive shots from the league’s leading scorer, Bob Pettit, which was no mean feat.”

After the game, Barry quoted Russell as saying he was nervous before the game started, that “I was a lemon at the foul line. I guess I really choked on ‘em out there.”

As time went by, “the big fellow” did manage to get the hang of things.